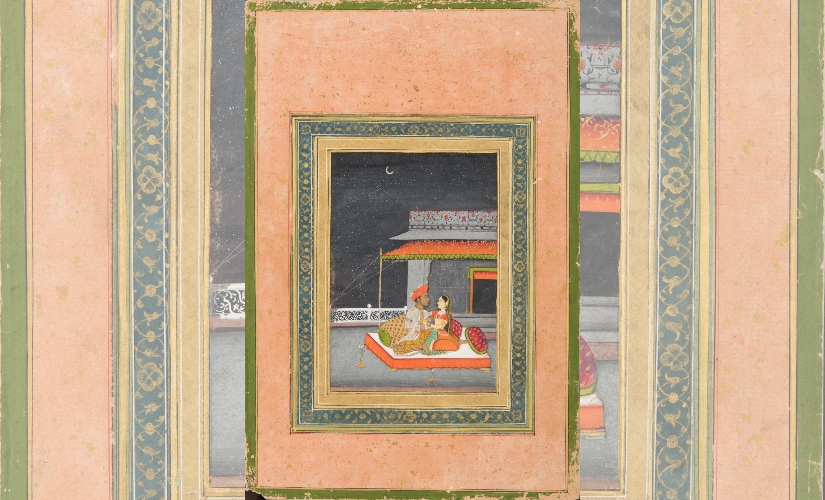

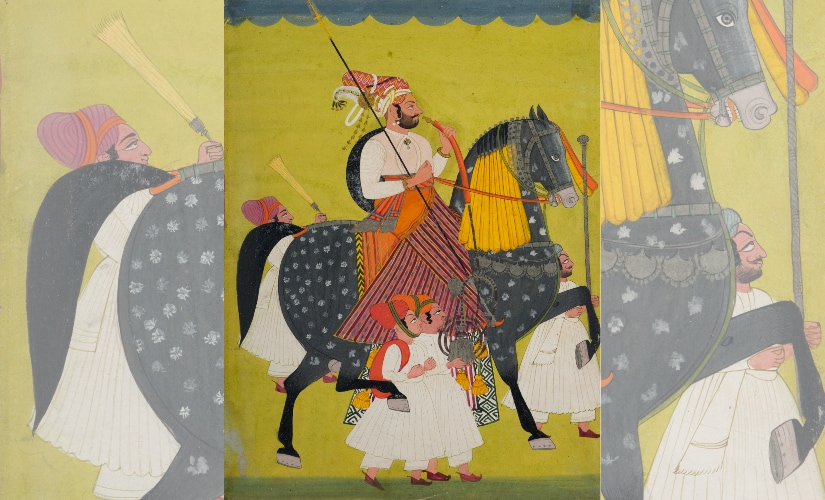

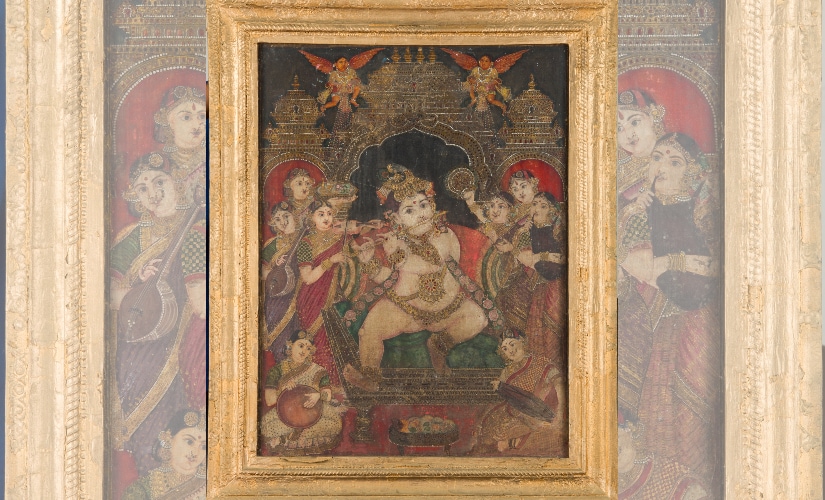

The canvas, as it existed in the Western art world, first came to India with the arrival of British painters in the late 18th century. These painters travelled across the country, and soon, Indian artists took to the canvas too, resulting in the emergence of institutions like the Dutch Bengal School of painting. But what were the styles of art that existed in India before this surface was embraced? A new exhibition at the Piramal Museum of Art seeks to answer this question through an offering of paintings on palm leaves, paper, cloth and even mica – all produced in the Indian subcontinent between the 16th and 18th centuries. Before The Canvas, curated by art historian Vaishnavi Ramanathan, follows another exhibition that was housed in the same gallery – Making Art, which focused on how materials play a key role in creating art and ideas. [caption id=“attachment_7144791” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  A Pahari miniature painting[/caption] “Each surface has its own quality, which affects the technique of the artist and the final product. We wanted to look at the kind of traditions that developed as a result,” Vaishnavi Ramanathan says. The visitor is greeted first by paintings on palm leaves – a style that flourished in Western and Eastern India because of the easy availability of this surface. They were illustrated accompaniments to religious texts (Jain and Buddhist texts) and were owned by mattas and religious bodies. Paper came to India in the 14th century, and it didn’t have the restrictions that accompanied palm leaves. “While palm leaf manuscripts were horizontal, paper allowed the paintings to be made in vertical formats. Palm leaves also came with restrictions of size, which was not an issue with paper – a big advantage,” Ramanathan explains. Persian and Mughal miniatures follow the palm leaves; the former have been included in this exhibition because Mughal paintings borrowed heavily from them. “Persian artists Mir Sayed Ali and Abdul Samad were brought to India by Humayun, and they started an atelier here. The Mughal atelier included a group of artists who were working together. The master artist would only come in at the final stages, to paint the finer details – to literally give life to the painting,” Ramanathan says. Members of the royal family, fakirs, saints and animals were all common subjects. Under each Mughal emperor, a certain style of painting flourished, she added. For example, Akbar’s paintings were very energetic – which stemmed from his own personality. “The colours are very jewel-like in Mughal paintings. They followed a certain method of applying colours: They would apply one layer and then burnish it. This ensured that the colour stuck on, and only then did they apply the next layer of colour. It was a very laborious process,” Ramanathan explains. [caption id=“attachment_7144751” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  An example of a Provincial Mughal painting, titled ‘Lovers on a terrace by moonlight’[/caption] Exhibited next to the Mughal miniatures are paintings in the Provincial Mughal style – a localised one that was practiced in places like Lucknow and Faizabad. “It’s a combination of the Mughal style with local influences. Because it emerged at a later period, you’ll find that the colours have gotten slightly muddy; they don’t have the same jewel-like quality,” Ramanathan says. After the fall of the Mughal Empire, many artists lost patronage. They moved to other states and the desert kingdoms. Schools flourished thereon, like the Rajasthani Miniature School and the Pahari School. “In the Rajasthani School, one finds the use of very bright colours. The subjects that were painted were royalty, kings in acts of devotion, the shringaar ras, and hunting scenes,” she says. The Rajasthani miniatures which are on display as part of this exhibition showcase episodes from the Ramayana, accompanied by text. Their provenance is not known, but the style and size seem to suggest they are part of the same manuscript, probably made after 1700 or so, the curator adds. [caption id=“attachment_7144781” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Thakur Madho Singh, painted in the Rajasthani miniature tradition[/caption] The Pahari miniature tradition evolved in the hills of Himachal, Kangra and Guler. “It has a very different sensibility as compared to Rajasthani miniatures. The landscape itself is very different, the colours used aren’t as bright. There’s a sense of refinement and delicacy to the paintings,” Ramanathan says. She adds that the painters worked with squirrel hair brushes because the hair had a natural curve, which allows one to draw very fine lines. In contrast to the delicate nature of miniatures is the Kalighat School of painting, practised by rural Bengali artists who migrated to suburban Calcutta. These paintings would be sold to the people who visited the Kalighat temple. “Apart from gods and goddesses, the painters would also depict contemporary subjects and events, like dandy men and their mistresses (a result of the West’s influence) and a sensational murder in the city. This was a school of painting that was very much in touch with the sentiments of the people,” Ramanathan explains. The artworks had to be sold at a low price, so the artists did not labour over lines. Cheap paper also became available in this period, the curator adds. [caption id=“attachment_7144761” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  A goddess painted in the Kalighat style[/caption] The Mysore and Tanjore styles, which are also on display at the exhibition, can be studied through comparison. Illustrations that were made for a book gradually turned into what we now know as the Mysore school. The paintings were made on paper, and unlike Tanjore paintings, the works aren’t as ornate. The painters did not use precious stones, instead opting for gesso work with gold foil applied on top. Goddess Saraswati is a characteristic subject of this school, and another aspect that defined it was the use of a particular shade of green – a shade that is not found in Tanjore paintings. To prepare the surface for a Tanjore painting, artists drape cloth over wood and cover it in chalk powder and gum. “The Tanjore School involves an elaborate technique whereby the artist begins by drawing outlines, accompanied by gesso work. Then they would encrust the stones into the painting. The process of sticking on gold foil is extremely laborious because you have to cut it accurately and stick it. They would also use semi-precious stones and glass,” Ramanathan says. With time, the usage of gold increased. Common themes in this school are the coronation of Rama and depiction of Krishna. [caption id=“attachment_7144771” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  An example of a Tanjore painting[/caption] [caption id=“attachment_7144741” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  A Pichvai painting; these paintings follow a standardised iconography in order to depict the various lilas of Krishna[/caption] An example of painting on cloth – the surface was an important support for painting in India – is the Pichvai style, which are named so because the artworks were hung behind deities’ idols. The art form emerged in Western India and was displayed in havelis and temples. “Each pichvai is made for a certain occasion. The painters would work with animal hair brushes, which is why they could achieve such fine lines. The artworks were funded by the temple and devotees. Sometimes, devotees would include their own portraits in the painting to mean that they are eternally worshipping the god,” Ramanathan says. Glass paintings were a simplified version of the paintings from the Tanjore School, the curator informs. They attained popularity because they weren’t as expensive and it did not take artists very long to paint them. “They’re reverse paintings on glass, which is complex and requires planning on the part of the artist. They would use mercury for some areas in the paintings which would appear like mirrors,” she explains. Britishers stationed in India wanted to take back Indian souvenirs when they were to return, and this led to the popularity of mica paintings. The style emerged in Murshidabad and spread to Varanasi and Lucknow. It was also practised in South Indian towns like Srirangam and Tanjore. It was a very novel surface for artists to work on. “The subjects were exotic – deities, Indian landscape, nautch girls and people. It is a difficult medium to work on because it is very smooth, so very fine work cannot be done on it. This is one of the reasons why this school died over time,” Ramanathan says. [caption id=“attachment_7144801” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  An untitled Mica painting[/caption] That the diversity of material led to diversity in styles is partly true, Ramanathan says. “As art historians, we like to think of diversity of style and approach it from a top-down view, but the artist has to work with certain ground realities – considerations of design, material and cost. For example, an artist may find the medium exciting and challenging, but he may not have the means to acquire a piece of ivory,” she explains. Most of the painting styles featured in Before The Canvas are living traditions, Ramanathan informs, though they may be practised very differently now, owing to changes in patronage and the availability of material. “Artists also face a lot of trouble when it comes to sourcing material. For example, the yellow that is used in miniatures is traditionally made from cow’s urine; the cows would be fed mango leaves for this purpose. In some cases, they would use lapis lazuli, a precious stone… Sometimes artists use the colours their parents left behind,” she adds. One of the challenges of curating an exhibition like this is determining what is ‘Indian’ and what is not, says Ramanathan; the artworks were produced at a time when the idea of India did not exist. “It is tough to determine borders in this respect, which is why we refer to the Indian subcontinent in this exhibition… Kalighat paintings, for example, were made in Bengal and some of the region is now Bangladesh. Some of the other painting traditions featured in the exhibition also go into Pakistan,” she explains. A related observation about these artworks is that many of them were not immune to the influence of Western art, particularly British painting which seeped in in a more widespread manner with the arrival of the East India Company. The presence of cherubs in Tanjore paintings, the checkered floor in a Pichvai painting are all examples of this. “Even during the Mughal era, the influence of Western artists still existed. This is why some Mughal paintings depict figures like Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary with a bindi,” Ramanathan explains. Before The Canvas will be exhibited at the Piramal Museum of Art from 11 August to 15 November, 2019

Before The Canvas features paintings on a variety of surfaces such as mica, glass, paper and palm leaves. The exhibition is a study in how the choice of surface impacts the technique of the artist and the final product

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)