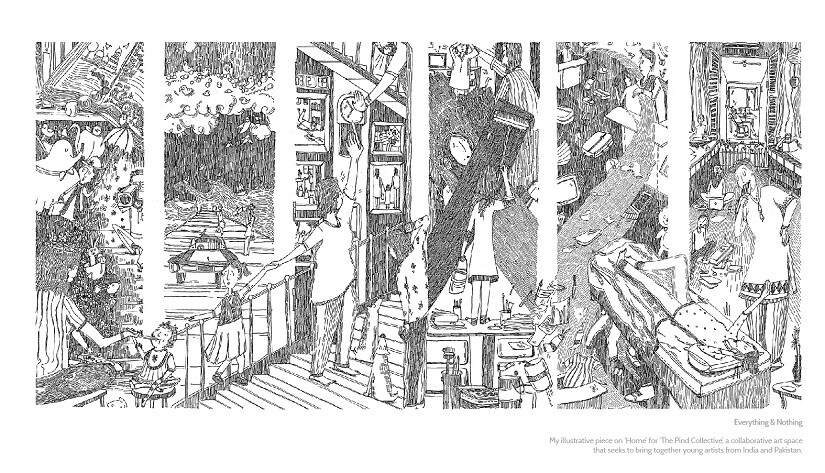

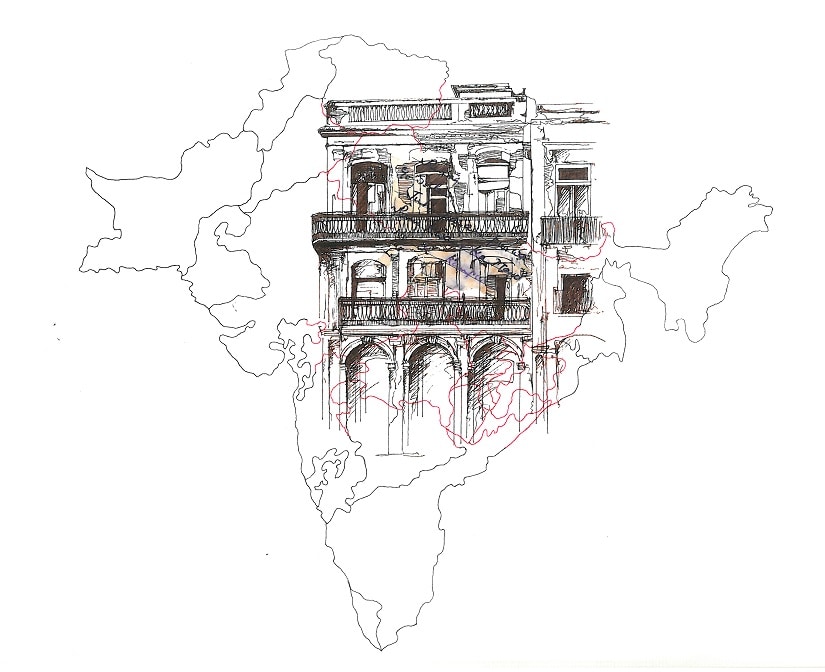

Around the 70th anniversary of India’s Independence Day, all roads led back in time — in most cases, towards the Partition. In a way, we are all Partition’s children. The dichotomy of states that came out the other side of India gaining independence, continues to define to this day, our economy, our policy, even our ideas of nationalism and patriotism. While every scholar, writer, historian, filmmaker etc worth his/her salt has found substance in this backwards journey to a time when both India and Pakistan were one, few have tried to map the contrasts or conscience that have evolved since. ‘The Pind Collective’ was born out of an idea to bring the journey since, to the fore — through artists from both India and Pakistan. The Pind Collective has brought together 10 artists from both India and Pakistan, who respond to a common theme in the first leg of the project, and subsequently to each other’s creations. “This project began several years ago, with a trip I took to Lahore in 2013. Growing up, Pakistan is a vague, but constant presence for most of us — you read about it in class, you hear about it on the news. It’s around, but it’s little more than a patchwork of images. When I actually visited, it was different and but also very familiar,” Avani, the co-founder of the project, says. Avani repeatedly invokes the presence of a physical border between a people that were and still are very much alike. In the digital age, the need to cross over a line towards familiarity is where The Pind Collective found it would best fit. [caption id=“attachment_4001239” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  ‘Everything and Nothing’ by Sneha Dasgupta. Image courtesy The Pind Collective[/caption] [caption id=“attachment_4001243” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  ‘Diary of a Vagabond/Jis Desh Main Ganga Behti Hai’ by Sarah Hashmi. Image courtesy The Pind collective[/caption] Says Ansh, the collective’s co-founder with Avani, and also a participating artist: “I thought the idea had immense potential. For a long time, I’ve felt that art in isolation begins to lose relevance and at some point, ends up being reduced to an indulgence. So what started as a conversation about what Avani initially thought this could be, slowly turned into a conversation about where we could take it from there." The two soon agreed on the theme of ‘Home’, this virtual, yet personal idea of a tangible structure representing your identity. In the context of India and Pakistan, this identity has gone through so much churn. That said, the collective’s preference for artists of a certain age, being representative of the third generation points to a view beyond remembrance or dreary nostalgia. “With Partition, a lot of our conversations consider inherited trauma and ideas of the nation that we once were. While this is important — of course we must pause to consider what has been lost — we also want to use this project of remembrance to consider what lies ahead. When we allow our sense of nationhood to be second-hand, given to us by our parents and grandparents, we relinquish the immense power to shape our own realities,” Avani says. The collective’s functioning is pretty straightforward. Artists on both sides of the border are given a common theme — for the first leg it was ‘Home’, for the second it will be ‘Resistance’ — and they are expected to respond to it in the way they best know. Subsequently, artists are paired and asked to respond to each other’s pieces. [caption id=“attachment_4001249” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  (L) Nade Ali’s response piece to Sthira Bhattacharya’s poem, ‘A Day Stretched Like A Blanket’, is an ongoing photo series that he’s undertaking in Lahore; (R) Visitors at the Khoj, New Delhi. Images courtesy The Pind Collective[/caption] The collective’s artists range from poets, painters, photographers to Dastangois and illustrators. Each sees Art in a different way. At this point you wonder if they talk to each other, from across the borders. “Our artists communicate chiefly through their work — whether it is by creating response pieces or by expressing appreciation for each other’s art. What remains deeply valuable to our project is that we do not limit what shape these conversations can take. Engagements between people of different nationalities are bound to carry inflections of their cultural and national identities. But we resist a sense of bounded-ness — a belief that India-Pakistan politics is all that we can discuss,” Avani says. “The experience of somebody in Karachi often echoes that of somebody in New Delhi. It’s incredible to see how diverse these conversations can be,” Ansh adds. Recently, the Collective had its first exhibition at the Khoj, New Delhi. With its second season now coming up, the project looks set to go from strength to strength. In doing so, it may find something more than the feeling of having been separated 70 years ago, and moving apart since. “It’s hard to pin down an authentically ‘Indian’ or ‘Pakistani’ aesthetic. Having said that, cultural markers often inform artistic practice and our nations have a lot in common — in terms of food, dress, and even language. I was recently looking at a poster that one of our participating artists created to commemorate Pakistan’s 70th anniversary of independence, and I was struck by how easily the motifs she had chosen could be used for a similar celebration of Indian independence," says Avani. “It’s odd how much you discover when you stop looking for difference.”

The Pind Collective has brought together 10 artists from both India and Pakistan, to respond to themes like ‘Home’ and ‘Resistance’ in their artworks

Advertisement

End of Article

)