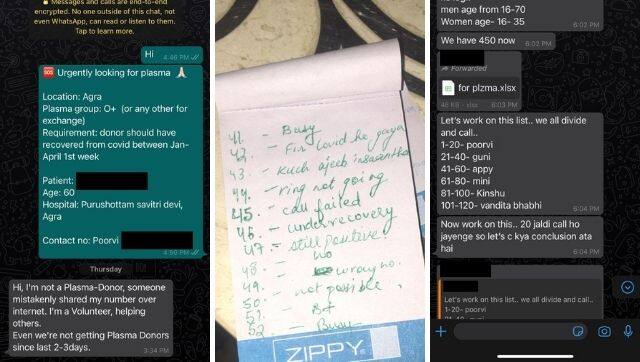

Poorvi Agarwal is a 25-year-old PR professional from Agra. The nightmare began a week ago. The doctor said my 60-year-old uncle, admitted to an Agra hospital after contracting COVID-19, needed plasma therapy. We did not worry much initially because his blood type is O positive, a group very common in our country and within our own family for that matter. However, that false optimism didn’t last long. It was the second day of our plasma hunt; the first had passed and left us at a dead end as none of us in the family had matched the suitability criteria to become a plasma donor. After that initial jolt, we sourced a list of 300 patients who had recovered from coronavirus between January and March. This is going to be helpful, we thought as we divided the names into age groups, focusing on those below 45. Each of us — the women and the elderly — began dialing the given numbers, while the male members left the house to arrange for an oxygen cylinder for my uncle during an extreme oxygen shortage in Uttar Pradesh. [caption id=“attachment_9592221” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Screenshots of our family group chats on Whatsapp.[/caption] Our house had turned into a call centre on the first day itself, so we knew the drill by now: as soon as someone picked up the phone, we let them know at the outset that we’d pay for everything — the transport cost, their PPE kit, and the compatibility test, of course. We were so desperate that we wouldn’t think twice before begging and pleading with the person on the other end to consider coming down to the blood bank. “It’s just blood for you, but it could save someone’s life,” I would say. While many simply cut the call, some told us they were still too weak to step out. Some said they were preserving blood for sick relatives who might need convalescent plasma therapy soon, and many recovered patients were just too paranoid to step into a hospital. However, I was most shocked when a person demanded Rs 1 lakh in exchange for plasma. In the midst of this, there was my uncle, who despite having an attendant was panic-stricken seeing as body after body was being lifted out of his ward.

Hours passed. The house wasn’t cleaned and no one bothered to eat. After making 300 calls, we found one person who was willing to take the compatibility test. He got tested along with seven of our family members, and yet after all the effort, no one had the desired antibody count. We could not believe it. First, there was the anxiety of time slipping through our fingers, and then the guilt of not being able to find a donor despite being a large family. Needless to say, no one slept that night. Even though we had exhausted all the options floating around through NGOs, websites, and social media (some of which hadn’t been updated in days), we would instantly sit up when someone sent us fresh details of a potential donor, even if it was in the wee hours. In those terrifying moments, I wondered why people couldn’t donate plasma when they were anyway stepping out of their homes to get vaccinated, or why an antibody test couldn’t be made mandatory for every recovered patient to make them comfortable with the idea of plasma therapy? _Read more from the Oral History Project here._ The next day brought respite. We found a donor in a distant relative, who had been inoculated but showed a stable antibody count. While the transfusion happened, we took my brother, who had just recovered from COVID-19, to get his antibody report. We did not want to waste a second in helping someone in need. Surprisingly, a request for plasma came in within a few hours, and my brother went and did the needful. So our family’s trauma aside, the experience taught us to always be prepared for a crisis. — As told to Anvisha Manral Write to us with your COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown experiences for inclusion in the Oral History Project at firstculturefeatures@gmail.com

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)