‘Top Notch’ is a fortnightly column where journalist and editor Namrata Zakaria introduces us to fashion’s elite and erudite club. *** What can be said of Abu Jani and Sandeep Khosla that hasn’t been said already? In their 35th year of working together, the duo is unarguably older than the organised fashion industry in India as we know it. They are renowned fashion designers, couturiers, costume stylists, revivalists, National Award recipients, confidantes to the snootiest of snobby Bollywood, peerless party-throwers, wickedest wits and, more recently, Clubhouse stalkers. And yet, 35 years is a very long time. They’ve seen the climb and fall and climb again of India’s clothing traditions. They’ve witnessed the opening of India’s economy, the arrival of international luxury and the triumph of homegrown traditions. Like Saleem and Shiva, the hero and anti-hero of Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, Abu and Sandeep are both players in and witness to India’s shifting sands. It’s perhaps just happenstance that one is a north Indian Hindu and the other a Mumbai-raised Bohri Muslim. Sandeep, the son of a wealthy industrialist from Kapurthala, went to posh boarding schools before he found his métier in Bombay. Abu was to the city born, slow-cooked in its multi-cultural cauldron with Parsis, Gujaratis, Madrasis, Anglos and Sindhis, like his mother’s famous mutton khichda (still the biggest draw at their soirées). They met, fell hopelessly in love and started a label with little else other than Rs 50,000 each. [caption id=“attachment_9675831” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

Deepika Padukone in an Abu-Sandeep creation[/caption] This was a time when the idea of an Indian fashion ‘designer’ was just taking shape. There were several others — Rohit Khosla, James Ferreira and the like — who wanted to break away from Indian clothes and wanted to Indians to dress the way a global consumer would. Embroidered clothes were made by housewives who employed a local masterji, without much design intervention and certainly no formal training or regulations. Other than Ritu Kumar, Abu-Sandeep (the two have become a collective noun) were the only ones responsible for steering Indian craft techniques to a luxury status then. Was it a risk, or where they playing safe? “It was a very big risk,” Sandeep says. “Revival is not cheap. One could get inexpensive wedding outfits made in Chandni Chowk or Bhuleshwar, but quality work cost a lot of money. Embroidered lehengas, made with just one type of naqshi stitch, were made in Bareilly and Lucknow but they were circular skirts and not panels. We had both worked for export houses in Bombay, and we especially wanted to rid India of the image it had of the maker of sequined butterfly-sleeve blouses and harem pants,” he laughs. “We wanted to bring the grandness of Indian fashion to the world, we wanted to show off the grandness of the stitch. The narrative of Indian fashion had to change.” “Crafts are dead the world over, but in India we have the availability of any kind of art, be it weaving, embroideries, inlay work, Tanjore paintings, sculpture. It would be foolish not to use these, we are blessed to have our artisans,” Abu echoes. Thus began their romance with craft. Abu-Sandeep never thought of the end consumer, they just focused on the poetry of their clothes. One item had 100 snakes on its neck, part of their first Mata Hari collection. They never thought anyone would buy it, but it put them on the cover of a magazine. They began to make expensive embroidered jackets and take them to the West, finding favour with celebrities like Shakira Caine, Princess Michael, Liza Minelli. “We were just two creative minds, neither of us had a brain for business,” Sandeep says. [caption id=“attachment_9675841” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

Deepika Padukone in an Abu-Sandeep creation[/caption] This was a time when the idea of an Indian fashion ‘designer’ was just taking shape. There were several others — Rohit Khosla, James Ferreira and the like — who wanted to break away from Indian clothes and wanted to Indians to dress the way a global consumer would. Embroidered clothes were made by housewives who employed a local masterji, without much design intervention and certainly no formal training or regulations. Other than Ritu Kumar, Abu-Sandeep (the two have become a collective noun) were the only ones responsible for steering Indian craft techniques to a luxury status then. Was it a risk, or where they playing safe? “It was a very big risk,” Sandeep says. “Revival is not cheap. One could get inexpensive wedding outfits made in Chandni Chowk or Bhuleshwar, but quality work cost a lot of money. Embroidered lehengas, made with just one type of naqshi stitch, were made in Bareilly and Lucknow but they were circular skirts and not panels. We had both worked for export houses in Bombay, and we especially wanted to rid India of the image it had of the maker of sequined butterfly-sleeve blouses and harem pants,” he laughs. “We wanted to bring the grandness of Indian fashion to the world, we wanted to show off the grandness of the stitch. The narrative of Indian fashion had to change.” “Crafts are dead the world over, but in India we have the availability of any kind of art, be it weaving, embroideries, inlay work, Tanjore paintings, sculpture. It would be foolish not to use these, we are blessed to have our artisans,” Abu echoes. Thus began their romance with craft. Abu-Sandeep never thought of the end consumer, they just focused on the poetry of their clothes. One item had 100 snakes on its neck, part of their first Mata Hari collection. They never thought anyone would buy it, but it put them on the cover of a magazine. They began to make expensive embroidered jackets and take them to the West, finding favour with celebrities like Shakira Caine, Princess Michael, Liza Minelli. “We were just two creative minds, neither of us had a brain for business,” Sandeep says. [caption id=“attachment_9675841” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

Shweta Bachchan-Nanda in an Abu-Sandep design[/caption] The first embroidery style the duo promoted was zardozi. Known as ‘zar-douzi’, this gold and silver sewing had its origins in Iran, Azerbaijan and Central Asia. Zardozi reached its apex in the 17th century in the court of Emperor Akbar, but arts and crafts came to a standstill under Aurangzeb first and then industrialisation. Then the two delved in bandhini, tie-dye knots from the Kutch, and crushed the fabric in a bid for modernity. This, they say, was copied from Kashmir to Kanyakumari. They began to put mirror-work on clothes after Rima Jain’s wedding, the daughter of Raj Kapoor. This wasn’t the Kutch-style abla, or tiny mirrors held together with colourful threads. These were large pieces of mirrors embroidered with gold and silver zardozi. And then came chikan, their signature and leitmotif. It’s said that nobody in the country makes chikankari more beautiful than Abu-Sandeep. Chikan, or shadow-work on muslin, mostly white on white, dates back to the 3rd century BC, and came to India as part of the Persian culture of Mughal rulers. It thrives in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, which is home to all its 32 stitches. “Chikan was an old love. I have an aunt, Sita Sondhi, who lives in Lucknow since the last 50 years. We took our own fabrics to her, and began to make large dupattas, like Muslim chadors. Seema and her friend Shenaz Kidwai took us to a printer called Mohammed Ali, who had the oldest printing blocks we had ever seen. No one used those prints anymore. He was startled to print on chiffon, as the fabric kept shifting. We did 30 blocks on one item, and each block had its own type of embroidery. We played old Hindi music and Shenaz sang, and we created magic. Mohammed Ali thought we were positively insane, he was probably right,” Sandeep laughs. The duo says Lucknow was so beautiful they wanted to move there and buy an old haveli. But these were decrepit, with only pigeons living in them, and didn’t come with proper paperwork. “It was a bit like the wild west,” they say, happy to make do with kakori and tunde kebabs instead. [caption id=“attachment_9675851” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

Shweta Bachchan-Nanda in an Abu-Sandep design[/caption] The first embroidery style the duo promoted was zardozi. Known as ‘zar-douzi’, this gold and silver sewing had its origins in Iran, Azerbaijan and Central Asia. Zardozi reached its apex in the 17th century in the court of Emperor Akbar, but arts and crafts came to a standstill under Aurangzeb first and then industrialisation. Then the two delved in bandhini, tie-dye knots from the Kutch, and crushed the fabric in a bid for modernity. This, they say, was copied from Kashmir to Kanyakumari. They began to put mirror-work on clothes after Rima Jain’s wedding, the daughter of Raj Kapoor. This wasn’t the Kutch-style abla, or tiny mirrors held together with colourful threads. These were large pieces of mirrors embroidered with gold and silver zardozi. And then came chikan, their signature and leitmotif. It’s said that nobody in the country makes chikankari more beautiful than Abu-Sandeep. Chikan, or shadow-work on muslin, mostly white on white, dates back to the 3rd century BC, and came to India as part of the Persian culture of Mughal rulers. It thrives in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, which is home to all its 32 stitches. “Chikan was an old love. I have an aunt, Sita Sondhi, who lives in Lucknow since the last 50 years. We took our own fabrics to her, and began to make large dupattas, like Muslim chadors. Seema and her friend Shenaz Kidwai took us to a printer called Mohammed Ali, who had the oldest printing blocks we had ever seen. No one used those prints anymore. He was startled to print on chiffon, as the fabric kept shifting. We did 30 blocks on one item, and each block had its own type of embroidery. We played old Hindi music and Shenaz sang, and we created magic. Mohammed Ali thought we were positively insane, he was probably right,” Sandeep laughs. The duo says Lucknow was so beautiful they wanted to move there and buy an old haveli. But these were decrepit, with only pigeons living in them, and didn’t come with proper paperwork. “It was a bit like the wild west,” they say, happy to make do with kakori and tunde kebabs instead. [caption id=“attachment_9675851” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

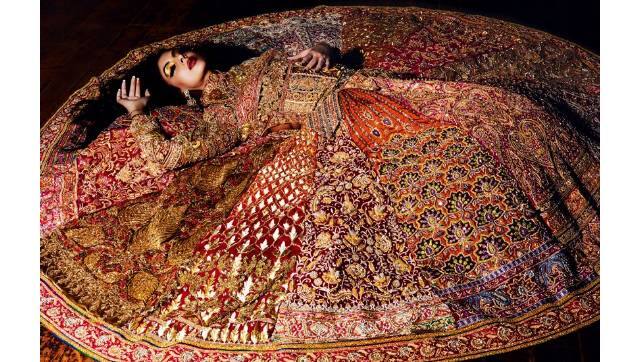

Designs by Abu-Sandeep. Photos by Joseph Radhik[/caption] The duo acknowledges India’s clothing traditions are completely dependent on its Muslim artisans. “The crafts are completely in the hands of the minorities. The best tailors and cutters, inlay artists, the finest carvers, they are all from minority communities,” Sandeep says. In Lucknow, the two would hold feasts for the young girls who embroidered chikan for them. They would gift them shawls, blankets, and utensils. The girls began to earn, were empowered, and found new respect among their families. In Bombay, Abu-Sandeep’s Diwali parties are celebrious. Bagging an invitation to one is much harder than one for a Bachchan party. The Juhu duplex, already brimming over with fine art and sculpture, has more film stars than a film magazine. Most of them are their generational friends and clients. Jaya Bachchan with daughter Shweta and granddaughter Navya Nanda, Dimple Kapadia with Twinkle Khanna. And Amitabh and Abhishek Bachchan, Akshay Kumar, Boney and the late Sridevi, Arjun Kapoor with Malaika Arora, and Varun Dhawan. But their Eid iftaars are where they truly celebrate with their family, their team. Most of these have been with the duo for 30 years. “We usually rent a restaurant where we pull out all stops for the feast. Our young design team performs a dance or a skit for the craftsmen,” they say. Abu-Sandeep have come to be the embodiment of India and her fashions, in its rich tapestry of multi-cultural apotheosis. As Abu sums it up: “None of the traditions were divisive. They came from all over the world, from Persia to China to Indonesia, we Indians have made them our own.”

Designs by Abu-Sandeep. Photos by Joseph Radhik[/caption] The duo acknowledges India’s clothing traditions are completely dependent on its Muslim artisans. “The crafts are completely in the hands of the minorities. The best tailors and cutters, inlay artists, the finest carvers, they are all from minority communities,” Sandeep says. In Lucknow, the two would hold feasts for the young girls who embroidered chikan for them. They would gift them shawls, blankets, and utensils. The girls began to earn, were empowered, and found new respect among their families. In Bombay, Abu-Sandeep’s Diwali parties are celebrious. Bagging an invitation to one is much harder than one for a Bachchan party. The Juhu duplex, already brimming over with fine art and sculpture, has more film stars than a film magazine. Most of them are their generational friends and clients. Jaya Bachchan with daughter Shweta and granddaughter Navya Nanda, Dimple Kapadia with Twinkle Khanna. And Amitabh and Abhishek Bachchan, Akshay Kumar, Boney and the late Sridevi, Arjun Kapoor with Malaika Arora, and Varun Dhawan. But their Eid iftaars are where they truly celebrate with their family, their team. Most of these have been with the duo for 30 years. “We usually rent a restaurant where we pull out all stops for the feast. Our young design team performs a dance or a skit for the craftsmen,” they say. Abu-Sandeep have come to be the embodiment of India and her fashions, in its rich tapestry of multi-cultural apotheosis. As Abu sums it up: “None of the traditions were divisive. They came from all over the world, from Persia to China to Indonesia, we Indians have made them our own.”

Abu Jani, Sandeep Khosla and the idea of India: How the designer duo came to embody the nation itself

Namrata Zakaria

• June 2, 2021, 12:36:48 IST

Like Saleem and Shiva, the hero and anti-hero of Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, Abu and Sandeep are both players in and witness to India’s shifting sands.

Advertisement

)

End of Article