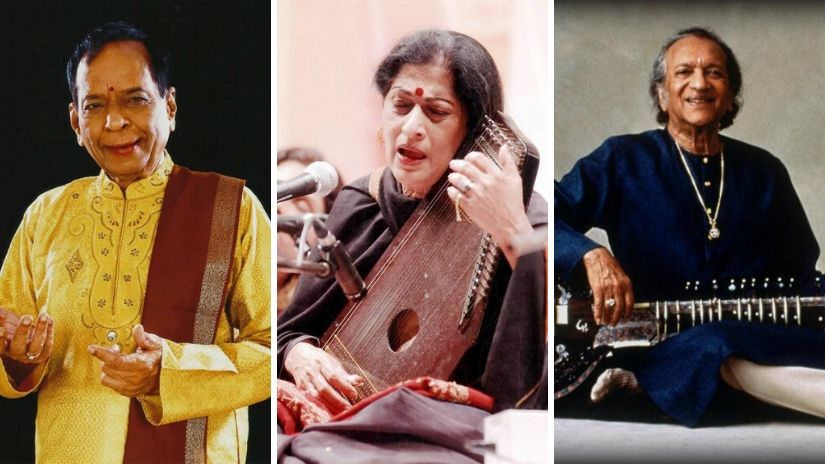

The last decade in Indian classical music, while on the face of it may have been in many ways similar to the one before it, has been markedly different on some counts. For one, this decade has seen the passing away of several luminaries. This would only be natural given that these stalwarts were born in the years preceding or around Independence, and rose to their glory in the 1960s through to the turn of the millennium. The last ten years have been witness to the loss of several trailblazing musicians in Hindustani and Carnatic music, including Bhimsen Joshi, Lakshmi Shankar, Ravi Shankar, Kishori Amonkar, Annapurna Devi, Girija Devi, Babanrao Haldankar, Abdul Halim Jaffer Khan, M Balamuralikrishna, Kadri Gopalnath and the untimely demise of artistes Veena Sahasrabuddhe and Ramakant Gundecha. All of these are among the more prominent names that come to mind, and undoubtedly there may be many other equally eminent musicians, mentors and musicologists born around the same time period who have now left behind either their teachings or a performance legacy or both. It does feel like the last decade has been the passing away of an era, doesn’t it? [caption id=“attachment_7835791” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  From left: M Balamuralikrishna, Kishori Amonkar and Ravi Shankar. Images via Facebook[/caption] “There are two philosophies with which one can view death,” says sitar maestro Shujaat Khan. “One is to fear death, to see it as a sense of loss, and with a sense of regret. The other is to view it as inevitable and with an acceptance and a celebration of a life that was. I don’t see this decade as the end of an ‘era’ because music cannot and must not be confined to eras,” he explains. Seconding this perspective, Ashwini Bhide avers that there is never going to be the end of an era, so to speak. “Their passing away is a natural, biological process. Death and life are ongoing processes.” Khan also opined that if one is at all, for the sake of discussion, to view the last decade as the passing of an era, it must also then signify the ushering of a new era, with newer artistes, concerts, and a different interpretation of our centuries-old music. “Sportsmen come and go, even governments come and go, and similarly, artistes come and they pass on. It doesn’t have to mean a closure forever. Newer artistes will come forward with the passing away of the older ones. That is how it has been, that is how it will always be.” How then does one deal with the pressure of being a torchbearer of a tradition going forward? Does it have any bearing on one’s perspective of music? “This is too hard to say. My perspective and presentation in music will be evaluated in the next 10-20 years, just like that of the performing artistes of the past. My only take on tradition is that I have to be true to my performance. When I get on stage and when I prepare to get on stage, I have to be able to build on this tradition set before me,” says Bhide considered today as among the most senior artistes to take forward the Jaipur-Atrauli vocal tradition. Tradition, no doubt, is the bedrock on which any classical art form rests, and Indian classical music is no exception. However, the performing arts have always seen an interesting interplay of tradition which symbolises permanence and culture — an ever-evolving phenomenon. The last decade has seen the rise of a musician not afraid to belong to the tradition and yet speak to the power of cultural inclusivity. Carnatic vocalist TM Krishna’s strong observations on politics, government and social discrimination on caste and religious lines have been a unique phenomenon given that most Indian classical artistes shy away from political commentary. Krishna has also pushed the envelope in terms of performances and collaborations — be it his performance with the transgender community, the Jogappas, or his work in setting to music the poetry of writer Perumal Murugan known for his brazen literature against caste-driven stigma and social exclusion. The emergence of India’s first all-woman classical music band Sakhi, led by vocalist Kaushiki Chakraborty, was another feature of note of the past decade. Formed in 2015, Sakhi brought together on stage Shaoni Talwalkar on tabla, Mahima Upadhyay on pakhawaj, Debopriya Chatterjee on flute, Nandini Shankar on violin, and Kathak exponent Bhakti Deshpande. [caption id=“attachment_7835831” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Clockwise (from top): Shujaat Khan, Ashwini Bhide Deshpande, Kaushiki Chakraborty and TM Krishna. Images via Facebook[/caption] While on the one hand the last decade has cemented the stature of a breed of artistes like Kaushiki Chakraborty thereby keeping alive the organic handing down of the classical music tradition, it has also seen the development of something a little more clinical and inorganic in its being — technology. Technology has changed the way in which ideas and information are accessed and consumed, music is no exception. YouTube took off around the turn of the millennium, proving to be a game-changer in the way the performing arts are chronicled, and is now firmly entrenched as the singular, most powerful platform to soak in the arts if one is unable to experience it live. Added to this, is the music app culture where a Spotify or an iTunes have spelt the death of the music CDs and changed the structure of music monetisation. “I never considered the CD as an avenue of income to begin with,” says Shujaat Khan. “The format just doesn’t work for our kind of music. It works as a wonderful source of revenue for more popular genres like film music or ghazals. But for me to earn a decent amount of royalty off of a classical music CD would require tens of thousands of them to be sold. No classical artiste can post such numbers. Furthermore, why should I depend on CD sales to begin with? My true joy as an artiste is when I see the audience enter the auditorium, sit down before me and partner with me on my journey in music in real life, in that moment. A CD could never ever lead to such a moment so it has made no difference to me that we have seen the end of CDs,” he admits with candour. And the instrumentalist is vociferous in his support of YouTube as a platform that democratises music; meaning that if one can listen to an established artiste, one can also listen to a budding artiste with limited means to market themselves. “YouTube reaches so many diverse forms of music from so many people to so many people. It is no comparison to the feel of listening to an artiste live, but I also have to acknowledge that it has brought in younger listeners into the concert hall. Today, I have almost 50 percent of my audience in the age category of 20-40. Isn’t that a good thing for our music and our tradition?” Khan asks. Bhide chooses to agree that the medium allows for undeniable reach. She, however, is quick to add that it also spells a loss of artistic control. “The YouTube experience is fleeting. I have no control over what a listener will download or the sound quality of the performance when it is heard off the internet. I also don’t know how long they will listen to a piece. These factors don’t matter when they are with me as an audience while I am on stage. YouTube doesn’t allow them to be part of my preparation as I go up on stage, as the instruments are being tuned and as I get to focus my entire being on my music. All of this is a part of the music even before it begins, and YouTube can’t deliver this experience. These moments are a crucial part of the process too,” she says.

Plus, one must consider this: if there are no live performances, there will be no recording of it on platform like YouTube, to begin with.

In her parting comment of what was memorable in terms of an event or performance in the decade gone by, Bhide makes a very crucial observation. “This is not about the last decade, but a performance that has stayed with me is from an event I was part of, way back in 1992 at the time of the communal riots in Mumbai. Several of us artistes had got together to perform and stand for communal unity; that has remained with me.” Asked if the time was right for something similar given the current political climate and she is quick to warn that one shouldn’t put words in her mouth. “There is no Hindu or Muslim for me in music is all I want to say, and that was the basis of the concert we had in Shivaji Park (in Mumbai). I have no other comment to make,” she says firmly, and with a clarity of thought that is the hallmark of her music as well. Last but far from the least, this past decade also saw two Indian names emerge on the Grammy scene in 2017. Tabla artistes Sandeep Das, won the award for his collaborative work with internationally-acclaimed cellist Yo-Yo Ma, while California-based tabla artiste Abhiman Kaushal was part of an album White Sun II which won Best New Age album at the coveted awards. So what will the 2020s bring? Speaking of the road ahead, Khan says his personal focus will be on his classical performances. “I have been a part of the thrill of collaboration that one gets from fusion music. It is a wonderful, cheerful experience and feels like a picnic on stage. There will always be those experiences and collaborations. But my truest sense of satisfaction is when I present my alaap, jod and jhala, spending time and taking you, the audience, through this process of unfolding the raga. I have no other plans other than this one for the decade forward or for any decade of the future,” he rounds off. **_Read more from our 'Decade in Review' series here._**

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)