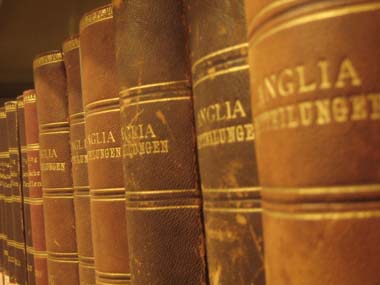

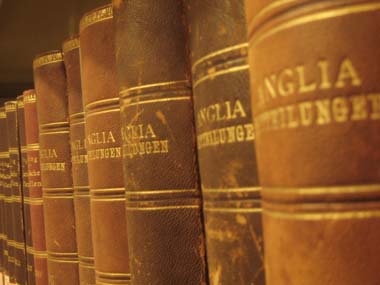

A couple of weeks ago, a friend emailed me a black-and-white image— artist and provenance unknown— that has haunted my thoughts ever since. Near the bottom right-hand corner of the sketch is a single wooden chair with a high back, so profoundly empty that it is almost magnificent in its loneliness. The chair faces a wall that is really an infinite bookshelf, throwing off a radiance that bathes the chair in the heart of its glow. For a bibliophile, that unending wall of books is a dream brought to life, and so naturally enough, it is at once exciting and terrifying, as if it belonged to the fantasies of a Jorge Luis Borges story. I was reminded yet again of this image when, last weekend, I read about Shaunna Raycraft, a woman in Saskatchewan whose house is reported to be collapsing under the weight of 350,000 books. The dauntless Ms. Raycraft apparently prevented these books— nearly 30 tons of them— from ending up in a neighbour’s bonfire, and although the books sit around in 7,000-odd boxes rather than grandly upon bookshelves, they have nevertheless filled a 1,100-square-foot house from floor to ceiling. “We’re kind of at a standstill,” Ms. Raycraft told The Guardian recently. “We have three kids and no time. And no money. And so we’re at the point now where we’re looking at having to burn some of the books ourselves.” [caption id=“attachment_25256” align=“alignleft” width=“380” caption=“To look upon a stack of books— or shelves of them— is to feel also a quickening of intellectual curiosity. Michael Graf from Flickr “]

[/caption] Ms. Raycraft rescued these books not out of a desire to read them, it appears, but out of a belief that the physical book is a thing worth saving. This is, needless to say, a belief that is increasingly regarded as regressive. In fact, now that methods of delivering many books to a single device have become cheap and efficient, it is surprising how the physicality of the book has begun to seem like a problem that was just waiting to be solved. So now we recall the many times we’ve shifted house, and how our books, packed into dense cardboard boxes, were always our most back-breaking possessions to move. In our ever-smaller apartments, we think of the space that can be freed up by replacing bookshelves— or, for some of us, eliminating the piles of books on the floor next to the bed or on a bathroom shelf. We calculate that we can now take two or three or even two hundred books with us on the Delhi-Chennai flight, so that if the one we’re reading begins to pall, we can switch to another one without exceeding our baggage weight limits. And suddenly, we remember that it is time to be more ecologically sensitive, and that books, manufactured as they are out of the corpses of trees, are no friends of the environment. These appeals to plain good sense are difficult to ignore, but somehow I have managed to ignore them. I am, admittedly, the kind of person that every e-book evangelist reflexively hates, the kind that goes on about the smell of old books and the texture of paper and the serene glories of browsing in bookshops. But my deep attraction to printed books also lies in their very material substance: in their impractical heft and weight, in the way they look when they are stacked up or shelved, and in the manner in which they occupy physical space in our lives. I know I am not the only person to feel this way. I have pored over too many blogs devoted to bookshelves and articles about private libraries— and read through too many of their enthusiastic comments— to feel alone in this odd aesthetic inclination. These blogs and articles, in fact, have made for hours of pleasant reading, although it can all turn covetous in seconds. When I read about Alberto Manguel’s library of 30,000 books — in a barn just south of the Loire Valley in France — and took in the photograph of burnished wood shelves bearing thousands of books in a handsome study, I nearly wept, torn between envy and admiration. There is both comfort and exhilaration to be derived from a physical book. We read, after all, to find answers, either existential or factual. The solidity of a book reassures us that answers exist, in a way that a virtual library, with no dimensions except an abstract sense of depth, cannot. To look upon a stack of books— or shelves of them— is to feel also a quickening of intellectual curiosity. There are answers in those books for which we, as individuals, may not yet have questions, and seeing books in their physical form pushes us to wonder whether we are even asking the right questions. More than anything else, a physical library holds the promise of containing the one book that will speak uniquely to us and change our lives. (Tantalizingly, like a poker player exposing one card of a crucial hand, the library will even show us the title on the spine of that one book, waiting for us to call.) The anticipation of finding that book is cut with the dread that we will never get to its particular position on the shelf; this is why I found the wall of books in that emailed image at once exciting and terrifying. And so we come back to Borges. Several days after I received the illustration of the infinite bookshelf, I remembered that there was indeed a Borges story that fit the image. In The Library of Babel, there are “an indefinite and perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries… In the vast Library, there are no two identical books.” For Borges, the library is the universe, and vice versa, but The Library of Babel contains one passage that explains the mystical fascination that book collections can exert over us.

[/caption] Ms. Raycraft rescued these books not out of a desire to read them, it appears, but out of a belief that the physical book is a thing worth saving. This is, needless to say, a belief that is increasingly regarded as regressive. In fact, now that methods of delivering many books to a single device have become cheap and efficient, it is surprising how the physicality of the book has begun to seem like a problem that was just waiting to be solved. So now we recall the many times we’ve shifted house, and how our books, packed into dense cardboard boxes, were always our most back-breaking possessions to move. In our ever-smaller apartments, we think of the space that can be freed up by replacing bookshelves— or, for some of us, eliminating the piles of books on the floor next to the bed or on a bathroom shelf. We calculate that we can now take two or three or even two hundred books with us on the Delhi-Chennai flight, so that if the one we’re reading begins to pall, we can switch to another one without exceeding our baggage weight limits. And suddenly, we remember that it is time to be more ecologically sensitive, and that books, manufactured as they are out of the corpses of trees, are no friends of the environment. These appeals to plain good sense are difficult to ignore, but somehow I have managed to ignore them. I am, admittedly, the kind of person that every e-book evangelist reflexively hates, the kind that goes on about the smell of old books and the texture of paper and the serene glories of browsing in bookshops. But my deep attraction to printed books also lies in their very material substance: in their impractical heft and weight, in the way they look when they are stacked up or shelved, and in the manner in which they occupy physical space in our lives. I know I am not the only person to feel this way. I have pored over too many blogs devoted to bookshelves and articles about private libraries— and read through too many of their enthusiastic comments— to feel alone in this odd aesthetic inclination. These blogs and articles, in fact, have made for hours of pleasant reading, although it can all turn covetous in seconds. When I read about Alberto Manguel’s library of 30,000 books — in a barn just south of the Loire Valley in France — and took in the photograph of burnished wood shelves bearing thousands of books in a handsome study, I nearly wept, torn between envy and admiration. There is both comfort and exhilaration to be derived from a physical book. We read, after all, to find answers, either existential or factual. The solidity of a book reassures us that answers exist, in a way that a virtual library, with no dimensions except an abstract sense of depth, cannot. To look upon a stack of books— or shelves of them— is to feel also a quickening of intellectual curiosity. There are answers in those books for which we, as individuals, may not yet have questions, and seeing books in their physical form pushes us to wonder whether we are even asking the right questions. More than anything else, a physical library holds the promise of containing the one book that will speak uniquely to us and change our lives. (Tantalizingly, like a poker player exposing one card of a crucial hand, the library will even show us the title on the spine of that one book, waiting for us to call.) The anticipation of finding that book is cut with the dread that we will never get to its particular position on the shelf; this is why I found the wall of books in that emailed image at once exciting and terrifying. And so we come back to Borges. Several days after I received the illustration of the infinite bookshelf, I remembered that there was indeed a Borges story that fit the image. In The Library of Babel, there are “an indefinite and perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries… In the vast Library, there are no two identical books.” For Borges, the library is the universe, and vice versa, but The Library of Babel contains one passage that explains the mystical fascination that book collections can exert over us.

“When it was proclaimed that the Library contained all books, the first impression was one of extravagant happiness,” Borges wrote. “All men felt themselves to be the masters of an intact and secret treasure. There was no personal or world problem whose eloquent solution did not exist in some hexagon. The universe was justified; the universe suddenly usurped the unlimited dimensions of hope.”

Samanth Subramanian is a contributing writer and the host of First Post’s literary salon. He is the Indian correspondent for The National and the author of Following Fish: Travels around the Indian Coast (Penguin, 2010).

)