Editor’s Note: Aman Sethi’s

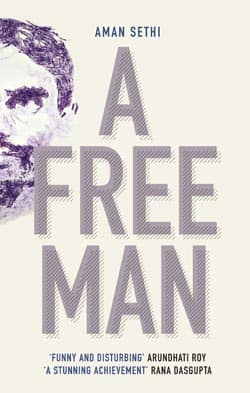

A Free Man

(Random House, Rs 399) is the latest book to confirm that the best Indian writing in English today is to be found in the non-fiction aisle. Funny, incisive, and moving in turns, the book is the culmination of the five years Sethi spent with daily-wage workers in New Delhi’s Sadar Bazaar in an attempt to understand a “mazdoor ki zindagi.” Sometimes those book blurbs have it right: A Free Man is indeed “an unforgettable portrait of an invisible man in his invisible city.” Sharmaji is a senior officer at the Beggars Court at Sewa Kutir, in Kingsway Camp in North Delhi. His job is to catch beggars and have them tried and punished in court. Begging in the national capital is a serious offence, and under the Bombay Prevention of Begging Act, 1959, the Department of Welfare can arrest all those “having no visible means of subsistence and wandering about, or remaining in a public place in a condition or manner, [that made] it likely that the person doing so exists by soliciting or receiving alms”. It isn’t just the alleged beggar; the law also has provisions for sending the family and dependants of the accused off to a remand home if the court feels they might turn to begging. [caption id=“attachment_46945” align=“alignleft” width=“380” caption=““But these beggars,” the exasperation in Sharmaji’s voice is palpable, “their hands are so dirty, so filthy, that the scanner just cannot pick up the image.” Reuters”]

[/caption] None of the men I know at Bara Tooti have any visible means of sustenance. If I saw Ashraf lying drunk on a pavement one evening, I wouldn’t know what to make of him. So how can Sharma_ji_ tell a beggar from a working man who is merely poor? “You can tell by looking at the hands. The rickshaw pullers, for example, have rough calluses here.” Sharmaji grabs my hand and points to the arc where the fingers join my palm. “It’s the rickshaw’s hard plastic handles. The skin first blisters, then the blisters become calluses and the calluses form little ridges.” “They also have big, bulging calves,” Sharmaji adds as an afterthought. “And some of them sit funny. “Mazdoor hands are different from beggar hands. They have calluses too—but their nails are scuffed from handling bricks and sand. You won’t see a rickshaw puller with scuffed hands. Safediwallahs tendy to be tall and lanky and are usually sprinkled with paint dust. Carpenters are Muslims and usually carry tools. Never, Aman sir, never trust a man who travels without his tools.” Sharmaji, raiding officer for the Department of Social Welfare and the source of these ethnographic insights, has rather soft hands himself — the sort that might be subjected to the occasional massage of Pond’s Cold Cream. But he has strong fingers and well-rounded shoulders: the anatomy of a man used to grabbing people and shaking them about. [caption id=“attachment_46941” align=“alignright” width=“250” caption=“A Free Man by Aman Sethi. Image courtesy Random House.”]

[/caption] None of the men I know at Bara Tooti have any visible means of sustenance. If I saw Ashraf lying drunk on a pavement one evening, I wouldn’t know what to make of him. So how can Sharma_ji_ tell a beggar from a working man who is merely poor? “You can tell by looking at the hands. The rickshaw pullers, for example, have rough calluses here.” Sharmaji grabs my hand and points to the arc where the fingers join my palm. “It’s the rickshaw’s hard plastic handles. The skin first blisters, then the blisters become calluses and the calluses form little ridges.” “They also have big, bulging calves,” Sharmaji adds as an afterthought. “And some of them sit funny. “Mazdoor hands are different from beggar hands. They have calluses too—but their nails are scuffed from handling bricks and sand. You won’t see a rickshaw puller with scuffed hands. Safediwallahs tendy to be tall and lanky and are usually sprinkled with paint dust. Carpenters are Muslims and usually carry tools. Never, Aman sir, never trust a man who travels without his tools.” Sharmaji, raiding officer for the Department of Social Welfare and the source of these ethnographic insights, has rather soft hands himself — the sort that might be subjected to the occasional massage of Pond’s Cold Cream. But he has strong fingers and well-rounded shoulders: the anatomy of a man used to grabbing people and shaking them about. [caption id=“attachment_46941” align=“alignright” width=“250” caption=“A Free Man by Aman Sethi. Image courtesy Random House.”]

[/caption] “Beggars don’t have any calluses. How can they if they never work? Also, a working man—no matter how poor he is—will always look you in the eye when he talks to you. But beggars? No, they can’t look me in the eye.” “Now take you, for instance.” He shakes my hand vigorously, somehow managing to point at me with my own fingers. “No one will mistake you for a beggar even if you dress up as one.” I try and imagine if I would look Sharma_ji_ in the eye. He reminds me of a particularly feared mathematics teacher from school — a man who appeared reasonable at most times, but could be moved to violence by completely innocuous acts. My teacher too had a habit of grabbing students by the shoulder and jerking them about, an experience I found intensely disorienting. This should be a period of frenetic activity for Sharma_ji_ and his team; the minister heading his department has promised to make Delhi “beggar free” in time for the Commonwealth Games in 2010. Sharma_ji’s_ department has deadlines to meet, beggars to deport, and cases to file. The target for the year is at least five thousand beggars. But the reception area is empty, save for the two of us, as are the small courtrooms. Sharma_ji’s_ raid vehicle has broken down, making it impossible for him to drive around the city chasing beggars. The wheels of the Delhi government do not move any faster for its own departments and so Sharma_ji_ has been told that a new vehicle will arrive “in some time”. “Right now, the only beggars we have are those rounded up by the Delhi Police. But they don’t know how to read hands. The police can’t tell a beggar from a beldaar.” Suddenly I am very afraid for my friends. Continue reading the excerpt on the next page “The police don’t even know how to catch them.” Sharma_ji_ is disconsolate. “There is a special technique. You can’t just stop anywhere and run at them. Now where would you go to catch a beggar?” “I don’t know. A traffic light?” “Wrong!” he says with some satisfaction. “Correct but wrong. Don’t worry, it is a logical mistake to make. You may find them at a traffic light, but you cannot catch them at a traffic light. You see the difference?” He grabs my wrist again. “We all know that beggars stand at traffic lights, but if you try and catch them, they often run off straight into traffic. The result? Accidents, traffic jams, and the public also gets upset.” Instead Sharma_ji_ and his team stake out at the major temples in the city. “It is the fault of our culture. If people spend lakhs of rupees in feeding the beggars, why would anyone work? All they do is sit and wait to be fed. This is not how you give discipline to the nation.” [caption id=“attachment_46942” align=“alignleft” width=“380” caption=“An Indian beggar carries her baby sister on a cold morning in New Delhi’s. Fayaz Kabli/Reuters”]

[/caption] “Beggars don’t have any calluses. How can they if they never work? Also, a working man—no matter how poor he is—will always look you in the eye when he talks to you. But beggars? No, they can’t look me in the eye.” “Now take you, for instance.” He shakes my hand vigorously, somehow managing to point at me with my own fingers. “No one will mistake you for a beggar even if you dress up as one.” I try and imagine if I would look Sharma_ji_ in the eye. He reminds me of a particularly feared mathematics teacher from school — a man who appeared reasonable at most times, but could be moved to violence by completely innocuous acts. My teacher too had a habit of grabbing students by the shoulder and jerking them about, an experience I found intensely disorienting. This should be a period of frenetic activity for Sharma_ji_ and his team; the minister heading his department has promised to make Delhi “beggar free” in time for the Commonwealth Games in 2010. Sharma_ji’s_ department has deadlines to meet, beggars to deport, and cases to file. The target for the year is at least five thousand beggars. But the reception area is empty, save for the two of us, as are the small courtrooms. Sharma_ji’s_ raid vehicle has broken down, making it impossible for him to drive around the city chasing beggars. The wheels of the Delhi government do not move any faster for its own departments and so Sharma_ji_ has been told that a new vehicle will arrive “in some time”. “Right now, the only beggars we have are those rounded up by the Delhi Police. But they don’t know how to read hands. The police can’t tell a beggar from a beldaar.” Suddenly I am very afraid for my friends. Continue reading the excerpt on the next page “The police don’t even know how to catch them.” Sharma_ji_ is disconsolate. “There is a special technique. You can’t just stop anywhere and run at them. Now where would you go to catch a beggar?” “I don’t know. A traffic light?” “Wrong!” he says with some satisfaction. “Correct but wrong. Don’t worry, it is a logical mistake to make. You may find them at a traffic light, but you cannot catch them at a traffic light. You see the difference?” He grabs my wrist again. “We all know that beggars stand at traffic lights, but if you try and catch them, they often run off straight into traffic. The result? Accidents, traffic jams, and the public also gets upset.” Instead Sharma_ji_ and his team stake out at the major temples in the city. “It is the fault of our culture. If people spend lakhs of rupees in feeding the beggars, why would anyone work? All they do is sit and wait to be fed. This is not how you give discipline to the nation.” [caption id=“attachment_46942” align=“alignleft” width=“380” caption=“An Indian beggar carries her baby sister on a cold morning in New Delhi’s. Fayaz Kabli/Reuters”]

[/caption] At temples, the beggars tend to be more docile and less likely to escape through rush hour traffic. “Temples, train stations, bus stands. Here you will not only find beggars, but also be able to arrest them. “It is best to arrive after they have been fed. Mid-afternoon to late evening, when they are drowsy and there aren’t too many pilgrims around.” Unsurprisingly, Sharma_ji_ also has a photographic memory. “I never forget faces—never. I will never forget your face. It is stored in my brain’s computer.” Since the Begging Act prescribes “Not less than one year and not exceeding three years for first time offenders. Ten years for repeat offenders,” raiding officers like Sharma_ji_ are often asked to testify if they had ever arrested the person before. “Obviously nobody gives the same name twice. So we have registers and registers of the same people—only stored under different names and addresses.” *** Most departments would have buckled under the weight of such voluminous and apparently useless data, but not the Department of Social Welfare which has already begun to computerize its registers. Equipped with the latest advances in biometric technology, the Beggar Information System or BIS 2.1 is “like our own passport office”. The machine is designed to store the details of every single person arrested by Sharmaji’s team: name, date of birth, place of birth, photograph, and biometric fingerprint. Once registered, the information is stored “forever”, implying that recidivists will no longer fool the judge by claiming that they got off a train in Delhi, were robbed of all their possessions, and were begging to get enough money to go back home. Once arrested, the beggars will be marched off to the registration room, photographed, fingerprinted, and presented before the court. If convicted, they are taken to one of twelve prisons set aside for beggars and locked up for a minimum of one year and a maximum of three. “So can I see this system?” I am eager to witness the information revolution at work. “Where is the machine stored?” “On the first floor.” Sharmaji is unsure. “It isn’t really working these days. We have called the technician, but after a point he stopped taking our calls.” Occasionally, the receptionist —who is on his lunch break— calls the technician from a different phone number from another department, but the technician has wised up to these tricks. “He says some part is missing and he shall come only when it arrives from the warehouse.” “I just want to see it. We don’t need to use it or anything.” “Come along then.” Sharmaji turns the key, and there it is, under a shroud of white plastic dust covers: the Beggar Information System Version 2.1. It is a record of every beggar with the misfortune of crossing Sharma_ji_ and his team. The machine is a rather bland-looking personal computer with little to distinguish it apart from a rather clunky-looking webcam and what appears to be a small plastic matchbox. Continue reading the excerpt on the next page “Is this it?” I find it hard to conceal my disappointment. “Well, yes. To be honest, we were a little surprised ourselves. We expected something a lot bigger.” “So this is the biometric reader?” I pick up the box and toss it in my hands casually. “Careful, Aman sir, careful. This is not a toy, this is a biometric device. The beggars place their thumbprint on the glass and the webcam takes their photo. That way we have full identification.” “So is the database searchable?” “There are a few small problems,” Sharmaji says sheepishly as he fires up the machine. The designers had failed to read the tender document carefully. The tender, freely available on the internet, clearly asks for “an interface to identify the habitual beggars at the time of reception by scanning the thumb impression or keying in other relevant information to establish the identity”, but this crucial detail had slipped the designers’ mind. Instead, the firm (whose name Sharma_ji_ coyly refused to reveal: “You are from the press, no? He he he”) had provided two separate interfaces — one for data entry and one for data search, thereby doubling the time required for registration instead of halving it. It was this particular software error that the technician appeared unable to fix till the “missing part” arrived. The other, more pressing problem lies with the scanner itself. Though the tender had mandated a “scratch-resistant” scanning surface, the scanner — as befitting any high-tech gadget —was extraordinarily sensitive to dust. It worked best when recording images of clean, slightly moist thumbs that, when pressed down onto the glass surface, flattened ever so slightly to allow for a true record of the fingerprint in question. [caption id=“attachment_46940” align=“alignleft” width=“380” caption=” Begging in the national capital is a serious offence. Reuters”]

[/caption] At temples, the beggars tend to be more docile and less likely to escape through rush hour traffic. “Temples, train stations, bus stands. Here you will not only find beggars, but also be able to arrest them. “It is best to arrive after they have been fed. Mid-afternoon to late evening, when they are drowsy and there aren’t too many pilgrims around.” Unsurprisingly, Sharma_ji_ also has a photographic memory. “I never forget faces—never. I will never forget your face. It is stored in my brain’s computer.” Since the Begging Act prescribes “Not less than one year and not exceeding three years for first time offenders. Ten years for repeat offenders,” raiding officers like Sharma_ji_ are often asked to testify if they had ever arrested the person before. “Obviously nobody gives the same name twice. So we have registers and registers of the same people—only stored under different names and addresses.” *** Most departments would have buckled under the weight of such voluminous and apparently useless data, but not the Department of Social Welfare which has already begun to computerize its registers. Equipped with the latest advances in biometric technology, the Beggar Information System or BIS 2.1 is “like our own passport office”. The machine is designed to store the details of every single person arrested by Sharmaji’s team: name, date of birth, place of birth, photograph, and biometric fingerprint. Once registered, the information is stored “forever”, implying that recidivists will no longer fool the judge by claiming that they got off a train in Delhi, were robbed of all their possessions, and were begging to get enough money to go back home. Once arrested, the beggars will be marched off to the registration room, photographed, fingerprinted, and presented before the court. If convicted, they are taken to one of twelve prisons set aside for beggars and locked up for a minimum of one year and a maximum of three. “So can I see this system?” I am eager to witness the information revolution at work. “Where is the machine stored?” “On the first floor.” Sharmaji is unsure. “It isn’t really working these days. We have called the technician, but after a point he stopped taking our calls.” Occasionally, the receptionist —who is on his lunch break— calls the technician from a different phone number from another department, but the technician has wised up to these tricks. “He says some part is missing and he shall come only when it arrives from the warehouse.” “I just want to see it. We don’t need to use it or anything.” “Come along then.” Sharmaji turns the key, and there it is, under a shroud of white plastic dust covers: the Beggar Information System Version 2.1. It is a record of every beggar with the misfortune of crossing Sharma_ji_ and his team. The machine is a rather bland-looking personal computer with little to distinguish it apart from a rather clunky-looking webcam and what appears to be a small plastic matchbox. Continue reading the excerpt on the next page “Is this it?” I find it hard to conceal my disappointment. “Well, yes. To be honest, we were a little surprised ourselves. We expected something a lot bigger.” “So this is the biometric reader?” I pick up the box and toss it in my hands casually. “Careful, Aman sir, careful. This is not a toy, this is a biometric device. The beggars place their thumbprint on the glass and the webcam takes their photo. That way we have full identification.” “So is the database searchable?” “There are a few small problems,” Sharmaji says sheepishly as he fires up the machine. The designers had failed to read the tender document carefully. The tender, freely available on the internet, clearly asks for “an interface to identify the habitual beggars at the time of reception by scanning the thumb impression or keying in other relevant information to establish the identity”, but this crucial detail had slipped the designers’ mind. Instead, the firm (whose name Sharma_ji_ coyly refused to reveal: “You are from the press, no? He he he”) had provided two separate interfaces — one for data entry and one for data search, thereby doubling the time required for registration instead of halving it. It was this particular software error that the technician appeared unable to fix till the “missing part” arrived. The other, more pressing problem lies with the scanner itself. Though the tender had mandated a “scratch-resistant” scanning surface, the scanner — as befitting any high-tech gadget —was extraordinarily sensitive to dust. It worked best when recording images of clean, slightly moist thumbs that, when pressed down onto the glass surface, flattened ever so slightly to allow for a true record of the fingerprint in question. [caption id=“attachment_46940” align=“alignleft” width=“380” caption=” Begging in the national capital is a serious offence. Reuters”]

[/caption] “But these beggars,” the exasperation in Sharma_ji’s_ voice is palpable, “their hands are so dirty, so filthy, that the scanner just cannot pick up the image.” All they got were blurry smudges that the machine was unable to identify, let alone catalogue and search. “So we started washing their hands before registering them. But that took too long.” The department also tried bathing them—but, after a bath, the beggars look “just like anyone else”. How then can the judge make his decision? “Now we register once manually before the hearings. And then again on computer in the evenings. That way we have complete records.” “But you can’t search them.” “We can.” Sharma_ji_ is quick to defend BIS 2.1. “It just takes some time, that’s all. In India, all everyone wants to do is criticise.” As I get up to leave, Sharma_ji_ points out three freshly bathed men leaving the reception centre. “The judge gave them a second chance.” I catch up with one of them on my way out. “Are you a beggar?” “Of course not, I’m a snake charmer.” “So where’s your snake?” “Sharma_ji_ asked me the same question. The Wildlife Department took it away.” This excerpt is republished from

Random Reads

, the in-house literary blog of Random House India. If you are in New Delhi, Aman Sethi will be discussing his book on 26th July at the Alliance Française de Delhi at 7 pm. Find the

details here

.

[/caption] “But these beggars,” the exasperation in Sharma_ji’s_ voice is palpable, “their hands are so dirty, so filthy, that the scanner just cannot pick up the image.” All they got were blurry smudges that the machine was unable to identify, let alone catalogue and search. “So we started washing their hands before registering them. But that took too long.” The department also tried bathing them—but, after a bath, the beggars look “just like anyone else”. How then can the judge make his decision? “Now we register once manually before the hearings. And then again on computer in the evenings. That way we have complete records.” “But you can’t search them.” “We can.” Sharma_ji_ is quick to defend BIS 2.1. “It just takes some time, that’s all. In India, all everyone wants to do is criticise.” As I get up to leave, Sharma_ji_ points out three freshly bathed men leaving the reception centre. “The judge gave them a second chance.” I catch up with one of them on my way out. “Are you a beggar?” “Of course not, I’m a snake charmer.” “So where’s your snake?” “Sharma_ji_ asked me the same question. The Wildlife Department took it away.” This excerpt is republished from

Random Reads

, the in-house literary blog of Random House India. If you are in New Delhi, Aman Sethi will be discussing his book on 26th July at the Alliance Française de Delhi at 7 pm. Find the

details here

.

Meet the beggar-catchers: How Sharmaji captures his prey

FP Archives

• July 23, 2011, 20:16:14 IST

The senior officer at the Beggars Court shares the special techniques our government uses to round up those pesky vagrants —including the high-tech Beggar Information System 2.1.

Advertisement

)