For the first time, the United States has reported a human case of the flesh-eating screwworm parasite, raising fresh alarm among authorities.

The infection was detected in Maryland in a traveller who had recently returned from Central America, where an outbreak of the parasite has been spreading northwards since late 2024.

Officials are now worried about what this could mean for the country’s livestock industry, as the US had successfully eliminated the parasite decades ago and was declared screwworm-free.

Here’s a breakdown of what’s happening and why it matters.

But first, what is a screwworm?

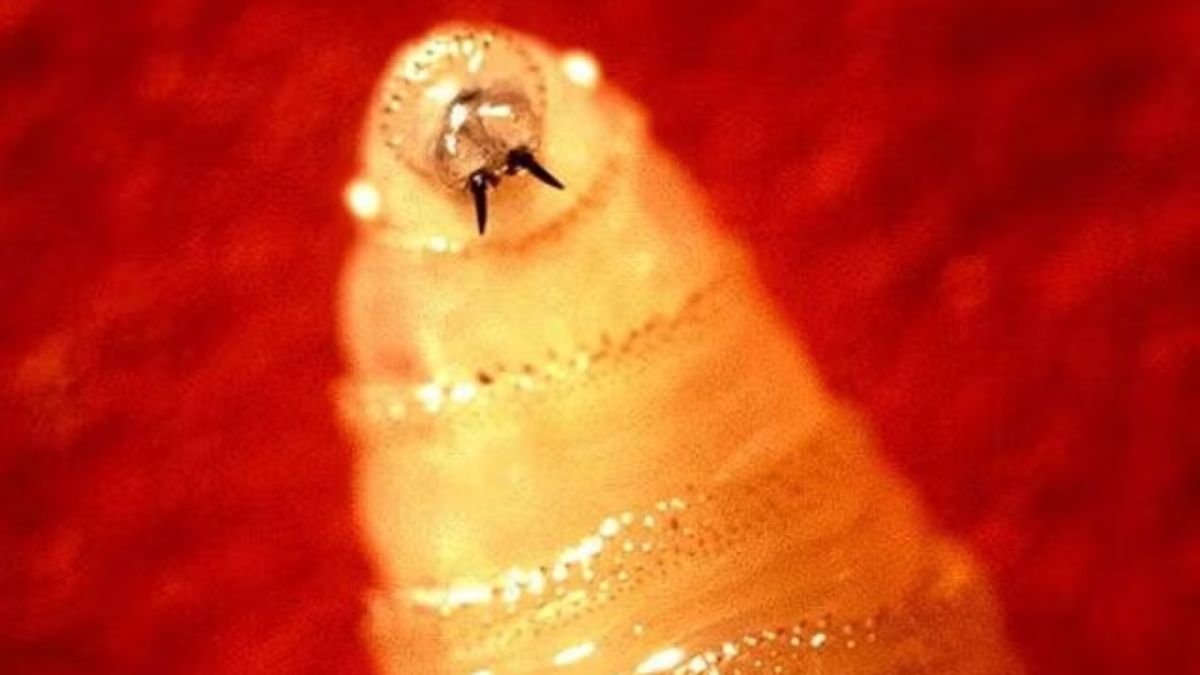

The New World screwworm (Cochliomyia hominivorax), often called NWS, is a parasitic fly found in Central and South America, the Caribbean, and parts of Mexico. Unlike ordinary maggots that feed on dead tissue, screwworm larvae survive only on living flesh.

Female flies deposit hundreds of eggs in open wounds of warm-blooded animals, including humans. Once the eggs hatch, the larvae begin burrowing deeper into the tissue with their sharp, screw-like mouths, which is how the parasite got its name.

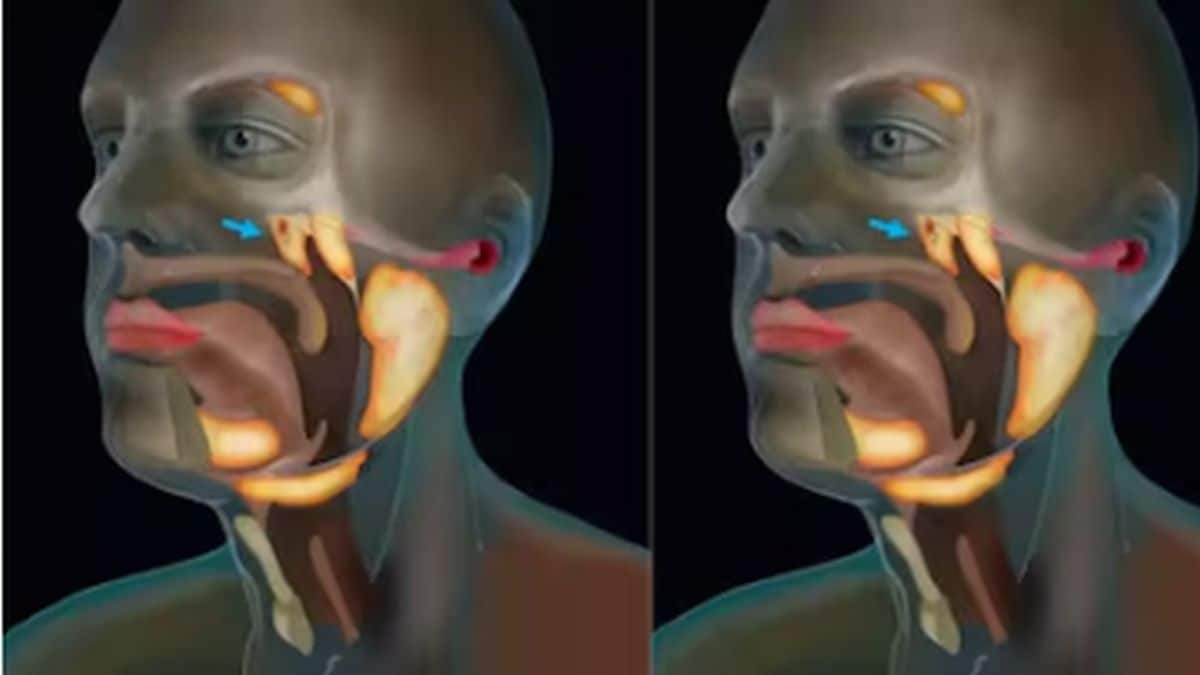

Infestation typically begins when a female fly targets an open wound or another vulnerable part of the body. While livestock are the most common hosts, birds and humans can also be affected. Even a small wound, as tiny as a tick bite, can draw the flies in. They’re especially attracted to places like the nose, mouth, eyes, genitals, or even the umbilical cord of a newborn animal.

If untreated, the condition, known as myiasis, can be deadly. And the scale of damage is enormous, just one female fly can lay as many as 3,000 eggs during her lifetime.

What are the signs & symptoms?

The CDC warns that New World screwworm (NWS) infestations are not only dangerous but also extremely painful. In many cases, maggots can be seen around or inside an open wound. In severe instances, they may even be found in the nose, mouth, or eyes.

Some common signs and symptoms include:

-Unexplained skin lesions (wounds or sores) that refuse to heal

-Wounds or sores that worsen instead of improving

-Painful open sores

-Bleeding from the affected site

-A foul-smelling odour coming from the wound

-The disturbing sensation of larvae moving within a wound, or in the nose, mouth, or eyes

-Visible maggots inside or around open sores

In addition, secondary bacterial infections can sometimes develop, leading to fever or chills.

What is the treatment?

The only way to treat a screwworm infection is by physically removing the larvae and cleaning the wound thoroughly. If caught early, patients usually recover without long-term damage.

Has the US faced an outbreak before?

Yes. The US actually declared victory over screwworm in the 1960s after a massive eradication effort.

The USDA used an innovative technique: releasing huge numbers of sterile male flies into the wild. Since female screwworms only mate once, these sterile pairings meant eggs never hatched, causing the population to collapse.

The strategy worked. The parasite was wiped out from US soil, and even a small outbreak in Florida in 2017 was quickly brought under control.

But the threat has resurfaced. A new outbreak began in Central America and southern Mexico in 2023, and cases have been moving north ever since, forcing US authorities back into emergency mode.

However, US Department of Health and Human Services spokesperson Andrew Nixon said the risk to the public is minimal. “The risk to public health in the United States from this introduction is very low," Nixon told Reuters. No animal infections have been confirmed in the US so far this year.

What is the US government doing now?

The latest detection comes just a week after USDA Secretary Brooke Rollins visited Texas to announce plans for a new sterile fly facility near the Mexico border. The plant, set to open at Moore Air Force Base in Edinburg, will take two to three years to become fully operational.

A sterile fly facility produces a large number of male flies and sterilises them, these males are then released to mate with wild female insects, which collapses the wild population over time.

Right now, there’s only one such facility in the world, in Panama, which can churn out around 100 million sterile flies each week. But USDA officials estimate they’ll need five times that number weekly to push the outbreak back to the Darien Gap, the dense rainforest between Panama and Colombia.

Mexico is also stepping up. The government has started building a $51 million sterile fly plant in its south to contain the spread before it reaches the US border.

Beef industry on edge

While human infections are uncommon, screwworms are devastating for livestock.

Texas A&M University estimates that a major outbreak in Texas could cause $1.8 billion in losses, from livestock deaths to treatment costs and extra labour. The timing couldn’t be worse: the US imports more than a million cattle from Mexico every year for beef processing.

The outbreak has already disrupted trade. Border closures, supply chain delays, and rising prices have followed reports of screwworm spreading through southern Mexico.

What’s adding to the industry’s frustration is the way information has been handled. Some ranchers and state officials say they weren’t kept in the loop by the CDC.

Beth Thompson, South Dakota’s state veterinarian, told Reuters she only heard about the Maryland case through informal channels.

“We found out via other routes and then had to go to CDC to tell us what was going on,” she said. “They weren’t forthcoming at all.”

Internal industry memos reviewed by Reuters also noted that the CDC was legally required to notify both Maryland health officials and the state veterinarian once the case was confirmed—something that, according to stakeholders, didn’t happen on time.

As one Beef Alliance executive reportedly wrote in internal emails (seen by Reuters), industry leaders feared a media leak could amplify volatility: “We remain hopeful that… the likelihood of a positive case being leaked is low, minimising market impact."

With input from agencies

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)