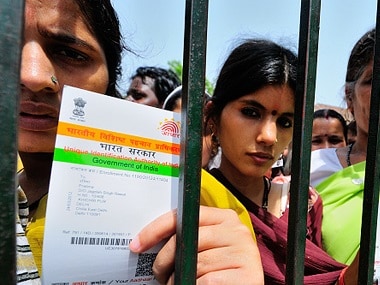

Recently, a 62-year-old woman in Jharkhand died in a bank queue after waiting for more than two hours under the scorching sun to withdraw money from her Jan Dhan account. In the midst of the extended lockdown, millions of poor women across India have been similarly queuing outside banks struggling to withdraw the government’s PM Garib Kalyan Yojana (PMGKY) cash transfers. [caption id=“attachment_5267941” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]

Representational image. Getty Images[/caption] On the other hand, in a public relations faux pas, television channels have aired videos of middle-class women with gold chains around their necks and fire extinguishers in their homes thanking the prime minister for the meagre ₹500 relief. The most tragic fallout of the COVID-19 lockdown is that it has exposed threadbare the class, caste and religious prejudices pernicious in Indian society. The haunting images of the exodus of penniless migrants fleeing industrial cities, inhuman police brutality and children dying of starvation in Dalit hamlets will be hard to erase from our nation’s collective memory. More ration shops than banks Even if we limit ourselves only to the banking system in the context of the current parsimonious PMGKY relief package, the acute class bias is evident on four fronts: First, only 29 percent of Indians have these Jan Dhan accounts, though their vision is to bank “every adult.” More importantly, 53 percent of poor women do not possess these zero balance accounts, as per

an estimate by Yale University.

Therefore, while on the other hand nearly half of poor households have been deprived, one of every four of these cash transfers to 200 million women’s bank accounts, have been dispatched to women who are essentially not poor.

Representational image. Getty Images[/caption] On the other hand, in a public relations faux pas, television channels have aired videos of middle-class women with gold chains around their necks and fire extinguishers in their homes thanking the prime minister for the meagre ₹500 relief. The most tragic fallout of the COVID-19 lockdown is that it has exposed threadbare the class, caste and religious prejudices pernicious in Indian society. The haunting images of the exodus of penniless migrants fleeing industrial cities, inhuman police brutality and children dying of starvation in Dalit hamlets will be hard to erase from our nation’s collective memory. More ration shops than banks Even if we limit ourselves only to the banking system in the context of the current parsimonious PMGKY relief package, the acute class bias is evident on four fronts: First, only 29 percent of Indians have these Jan Dhan accounts, though their vision is to bank “every adult.” More importantly, 53 percent of poor women do not possess these zero balance accounts, as per

an estimate by Yale University.

Therefore, while on the other hand nearly half of poor households have been deprived, one of every four of these cash transfers to 200 million women’s bank accounts, have been dispatched to women who are essentially not poor.

Future of cash transfers

Nevertheless, oddly, the Home Ministry on 25 March sanctioned BCs and ATMs to continue their respective banking operations. Telangana, Andhra Pradesh and Rajasthan have even passed specific orders. The finance minister too encouraged their operation. Despite the lockdown, the RBI has estimated that 80 percent of BCs are functional. However, the ground reality is that BCs are under acute strain with limited transport, police harassment and fear of infection. National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development has advised that BCs should be provided with health insurance given the high risk associated with their jobs. Some banks have sanctioned an extra honorarium to purchase masks, gloves, disinfectants and sanitisers. But, in reality most BCs are not adequately aware or

trained in the usage of disinfectants.

A pizza delivery employee in Delhi who tested positive for COVID-19 potentially put 72 families at risk. For BCs, the physical interaction and proximity necessary is even greater as customers necessarily need to place their finger impressions on the glass panel. While many studies are being conducted at a feverish pace and estimates vary, most agree that SARS-CoV-2 — the novel coronavirus that causes the COVID-19 disease — can survive on glass for four days, on surgical latex gloves for up to eight hours and as air droplets for three hours.

Therefore, as we enter an era with new waves of infectious global pandemics, it is essential to rethink the operations of BCs. Biometric authentication puts them and their customers at considerable risk of infection transmission even in asymptomatic stages.

Recognising this danger, the Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT) was quick to suspend Aadhaar-based attendance systems across government offices and Karnataka, Jharkhand and Kerala, among many other states, have discontinued biometrics in fair price ration shops. In the near future, it would be wise to altogether discontinue Aadhaar-based fingerprint authentication across welfare programmes and banking operations, which have anyways proved to be cumbersome and error prone. Other suitable technologies with lower risk of such as contactless cards , which also enable offline usage, can be considered as they are touch-free and retained by the customer. In countries like the United Kingdom they are more ubiquitous than even currency notes as tickets for public transportation, identity cards and bank credit cards. Recently, the Indian government too has begun to issue limited RuPay contactless cards. Every crisis presents an opportunity. Immediately, to quell the surge of hunger and unemployment, the food ministry must adopt a universal PDS with free foodgrain for at least six months. India also definitely needs to rethink the modality of cash transfers, BCs and biometric authentication as the world moves to a “new normal.” Business as usual will no longer be an option.

)