Kerala is battling a surge in infections caused by the brain-eating amoeba. The southern state has reported more than 70 cases this year and 19 fatalities.

The survival rate of about 24 per cent in Kerala is much higher than the global survival rate of around three per cent. But how is the state tackling cases of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM)?

We will explain.

PAM cases in Kerala

Kerala has logged 71 cases of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis this year. The rare brain infection is caused by Naegleria fowleri, an amoeba found in warm and shallow bodies of freshwater, such as lakes, rivers and hot springs.

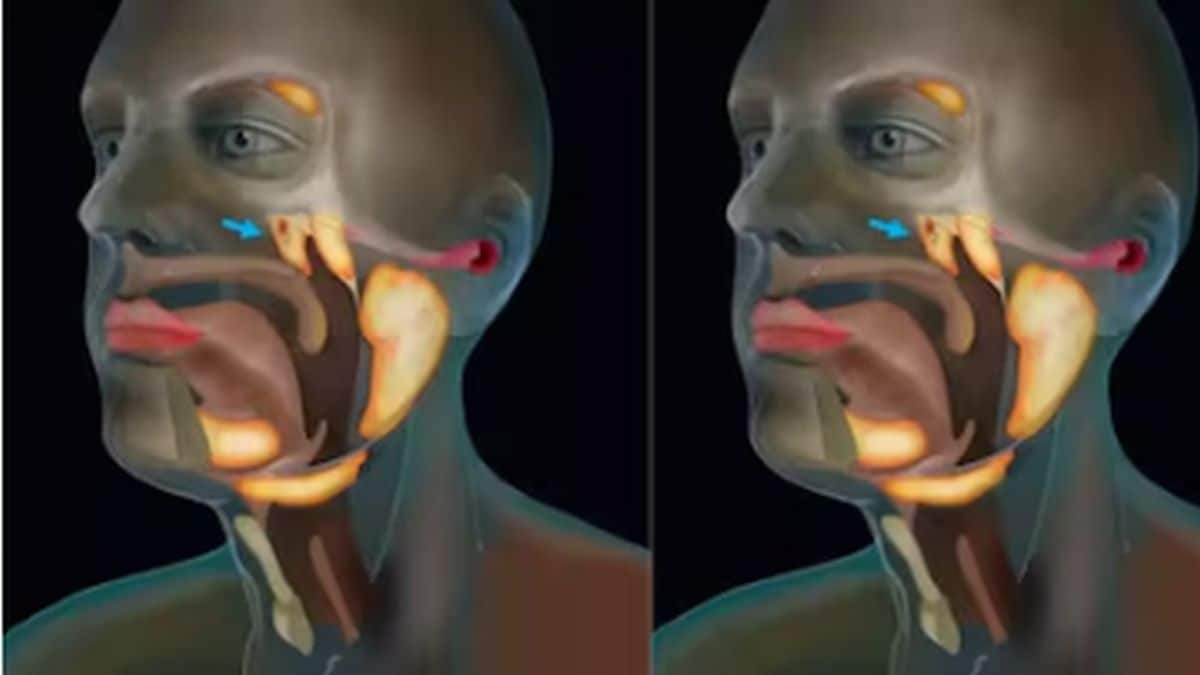

It enters through the nose, usually while swimming, and rapidly destroys brain tissue.

Patients in Kerala have ranged from a three-month-old to a 92-year-old man.

The state first reported a case of amoebic meningoencephalitis in 2016. This year, Kerala is seeing cases occurring sporadically across the state, according to Health Minister Veena George. “Unlike last year, we are not seeing clusters linked to a single water source. These are single, isolated cases, and this has complicated our epidemiological investigations,” she said earlier.

How dangerous is PAM?

The rare infection is nearly always fatal.

As per a new study, 488 cases of PAM have been reported globally since 1962. Most of these infections were in the US, Pakistan and Australia. About 95 per cent of the victims died from the disease.

Immunocompromised people are at higher risk of this rare infection, Dr Juan Fernando Ortiz, a neurology resident at Corewell Health in Grand Rapids, Michigan, US, told LiveScience.

Most people who contract an infection with _Naegleria fowleri_ die about five days after the symptoms begin.

Kerala fights back

Until recently, almost all primary amoebic meningoencephalitis cases in Kerala were fatal. However, the survival rate has been improving in the state.

In 2024, there were 39 cases with a 23 per cent fatality rate. This year, Kerala reported over 70 cases with about 24.5 per cent mortality, as per BBC.

Impact Shorts

More ShortsKerala has adopted a multi-pronged approach to tackle the rare disease. Early detection is key to saving lives when it comes to PAM.

Speaking to News18, Dr Harikumar S, Assistant Director (Public Health), Directorate of Health Services (DHS), Kerala, credited the state’s surveillance and early detection system for the increase in survival rate.

“It is the surveillance mechanism in Kerala that allows us to spot cases early, with clinicians following ready guidelines," he said.

Although PAM infections have risen, Kerala’s survival rate is far ahead globally.

“Cases are rising but deaths are falling. Aggressive testing and early diagnosis have improved survival - a strategy unique to Kerala,” Aravind Reghukumar, head of infectious diseases at the Medical College and Hospital in Thiruvananthapuram, told BBC.

As PAM looks like meningitis, doctors may not timely order the testing of cerebrospinal fluid, which helps detect the presence of the brain-eating amoeba. With this, as early detection is lost, the chance of survival reduces.

“If a patient comes with fever and meningitis-like symptoms, and all viral panel tests are negative, we conduct a cerebrospinal fluid test. If organisms are present, microscopy helps confirm the diagnosis. This saves patients before much damage occurs," Harikumar S said to News18.

A drug cocktail of antimicrobials and steroids can also help bring down the fatality rate. There are no standard treatments for the rare disease. Currently, doctors tackle it with a combination of drugs, including amphotericin B, rifampin, miltefosine, azithromycin, fluconazole and dexamethasone.

Kerala is reportedly using miltefosine for the treatment of infections caused by the brain-eating amoeba. An antimicrobial, the drug was originally used to treat leishmaniasis, an illness caused by a tropical parasite. Miltefosine has shown promise against N. fowleri in studies.

However, the drug can have toxic side effects on the kidneys and liver. And not all patients who received miltefosine have survived.

The National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) and Kerala’s health department are conducting epidemiological investigations, including environmental sampling and testing of water sources.

Public health measures such as awareness drives and chlorination of freshwater bodies are also underway.

Kerala, which has nearly 5.5 million (55 lakh) wells and 55,000 ponds, is more vulnerable to this rare disease. By the end of August, authorities in the state had chlorinated 2.7 million (27 lakh) wells.

Signboards have been erected around ponds warning against bathing or swimming. People have been urged to clean tanks and pools, keep children away from sprinklers and avoid unsafe ponds.

“We are also creating awareness about chlorinating fresh water bodies and storage tanks. State and public awareness drives as a prevention measure," the expert told News18.

With inputs from agencies

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)