The ‘God of Cricket’ scored the first of his hundred international centuries at Old Trafford, Manchester in 1990. A few days before embarking on that historic tour of England, the 16-year-old prodigy spent a couple of weeks preparing meticulously for the swing and pace of English wickets by practising at the Rashtriya Chemicals and Fertilisers (RCF) ground in Chembur. Later in his career, Sachin Tendulkar would visit the RCF sports complex for practise sessions, ad shoots etc. He even scored a Ranji hundred here in 1996, playing against Baroda. If memory serves me right, he was batting on 60 at lunch time and told the caterer to keep a bowl of chicken pieces aside for him to eat after he got a hundred! In 2014, RCF had organised a cricket tournament for public sector undertakings from all over the country. Keeping in mind Tendulkar’s special fondness for RCF, I wrote him a note requesting him to spend 10 minutes with the players and organisers, which, I had mentioned, would be a huge morale booster to both. The ‘Master Blaster’, perhaps, was too busy to reply. [caption id=“attachment_4238919” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

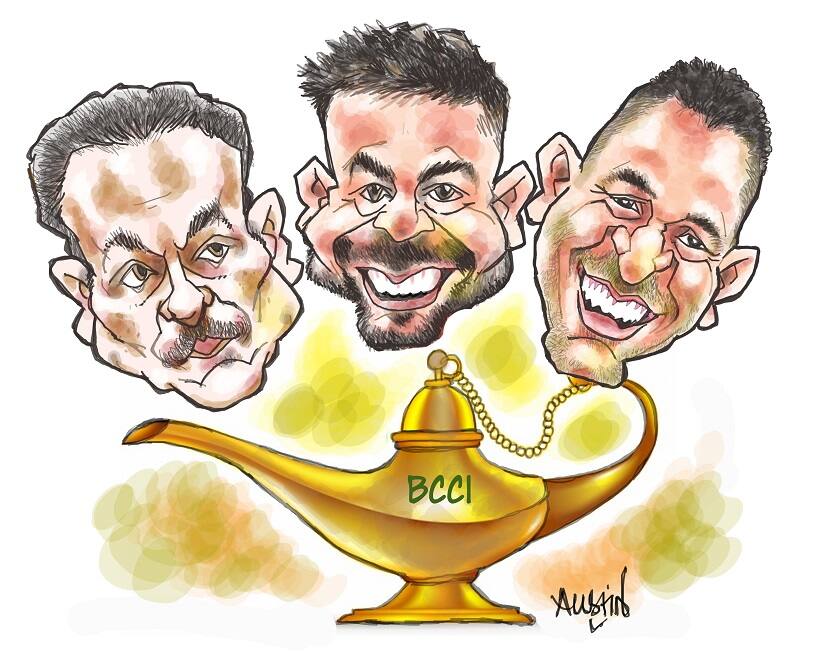

Today’s cricketers are a pampered lot. Illustration courtesy Austin Coutinho[/caption] Dilip Vengsarkar, Sanjay Manjrekar, Pravin Amre and many other celebrities of the ‘older generation’, however, made it a point to attend. In 1984, RCF had organised a special fitness camp for Mumbai’s talented young cricketers, supervised by world-cupper, Balvinder Singh Sandhu. Amre, from that camp, later went on to play for India and many others played first-class cricket. Sandhu had casually informed Sunil Gavaskar of the initiative. One day, unannounced, the ‘Li’l Master’ showed up at the RCF ground. Times have changed. Cricketing superstars are no longer accessible unless you ‘know’ their business managers. Indian players are now ‘commodities’ to be marketed at their ‘maximum retail prices’. Their lives, at least off the field, are run by their agencies, their managers and sponsors. I am afraid, even the most solemn of cricketing marriages and alliances these days are stage-managed for mileage and publicity by these PR managers. The ‘making hay while the sun shines’ predisposition has now trickled down to the Indian Premier League, where some of the players who haven’t even played first-class cricket look to make a fast buck. Nobody grudges them that moolah as long as it is through fair means. The Forbes list for the 100 highest paid athletes in the last year includes India skipper Virat Kohli. He is said to have grossed $22 million in 2017, i.e. R. 140 crore. He is the only cricketer in the list. A few years ago, MS Dhoni was there and before that there was Sachin Tendulkar too. Any cricketer, who plays all formats of the game and the IPL, even for a couple of years, is rich by Indian standards. In a land where the per capita income is around Rs 1.03 lakh, anybody with a net worth of Rs 30 to 40 crore would be considered to be prosperous. How many well-educated Indians can boast of such wealth at the end of a long corporate career? What’s more, for a player who is marketable and endorses dozens of products, the sky is the limit. Therefore, how much he earns through sponsorships, endorsements and ‘public appearances’, can only be a matter of conjecture. After the recent meeting between members of the CoA and Ravi Shastri, Kohli and Dhoni, it is believed that the annual contracts offered to Indian players would jump a 100 percent. Reliable sources tell me that some of cricket’s top celebrities, active and retired, demand as much as Rs 1 crore for making an appearance at showroom openings, product launches and even high-brow wedding receptions! The line dividing cricket and Bollywood has now been obliterated. Both are glamour jamborees and demand similar, star prerogatives and lifestyles. England’s cricketers get an equivalent of Rs 6 crore annually as retainers, while Australians are paid an equivalent of Rs 4.3 crore for the same period. Over and above this, they are paid match fees. Cricket salaries in both countries are up for revision and could see a substantial jump 2020 onwards. Once Indian cricketers’ annual contracts are revised, they won’t be badly off as compared to their English and Australian counterparts; especially when the cost-of-living index is taken into consideration. The cost-of-living index for Australia is 85.96, as compared to 76.02 in England and 67.50 in India. Now, let’s compare the amount of money that Indian cricketers make to what other star Indian sportspersons earn in a year. PV Sindhu, who won a silver medal at the Olympics in 2016, is said to have grossed Rs 18 crore from prize-money, awards and sponsorships in the last 12 months. According to sources, she has now signed a Rs 50 crore deal over three years, to endorse products. Sania Mirza and Saina Nehwal are said to have signed endorsement deals of around Rs. 16 crore each. Star footballer and India skipper, Sunil Chhetri earns something like Rs 60 lakh annually from match fees and was bought by his football franchise, last year, for Rs 1.2 crore. Indian hockey players earn much less. Sports minister Rajyavardhan Singh Rathore’s move to pay Rs 50,000 as a monthly stipend to more than 150 athletes who are preparing for the Asiad, the Commonwealth Games and the Olympics is therefore laudable. India will never be able to progress in international sport if our athletes can’t look after themselves and their families, and of course, aren’t able to afford special diets and training facilities. In a recent interview, former India skipper, Sourav Ganguly said that BCCI earns a lot of money and, therefore, players should be looked after well and paid handsomely. The BCCI will collect $2.55 billion for the IPL broadcast rights from Star Sports. There’s a bounty to be received from ICC and then, TV rights for the next few seasons is up for grabs. It is this money that has encouraged players to ask for their slice of the cake. ‘Money goes where money is,’ is an old adage. Ganguly is well within his rights as an ex-cricketer and administrator to push for salary reforms for international cricketers. So also are Shastri, Kohli and Dhoni. But what stops them from sparing a thought for and demanding a better deal for the country’s first-class cricketers? And what about the coaches and umpires who work tirelessly at the grassroots level or the curators and ground staff who are paid a pittance for their efforts? A couple of months ago, I was amazed by a ‘fun’ interview that Rohit Sharma did with newcomers Yuzvendra Chahal and Kuldeep Yadav on TV. When asked about their favourite cars, Chahal said, “Porsche” and Yadav said, “Ford Mustang – 1990s model.” This little conversation told me a lot about the level of confidence that an India cricket cap brings with it. Indian cricketers are indeed a pampered lot. To supporters of Indian cricket who believe that they have worked hard for it, I would like to ask, “Who hasn’t?” Ask a Sindhu or a Sania Mirza or a Sunil Chhetri, or even a Rajyavardhan Singh Rathore. Or for that matter, the cricketers of the 1970s-1990s who worked hard to make Indian cricket what it is today. The author is a caricaturist, sportswriter and mental toughness trainer. He was a fast bowler and Mumbai’s Ranji probable in the 1980s.

Today’s cricketers are a pampered lot. Illustration courtesy Austin Coutinho[/caption] Dilip Vengsarkar, Sanjay Manjrekar, Pravin Amre and many other celebrities of the ‘older generation’, however, made it a point to attend. In 1984, RCF had organised a special fitness camp for Mumbai’s talented young cricketers, supervised by world-cupper, Balvinder Singh Sandhu. Amre, from that camp, later went on to play for India and many others played first-class cricket. Sandhu had casually informed Sunil Gavaskar of the initiative. One day, unannounced, the ‘Li’l Master’ showed up at the RCF ground. Times have changed. Cricketing superstars are no longer accessible unless you ‘know’ their business managers. Indian players are now ‘commodities’ to be marketed at their ‘maximum retail prices’. Their lives, at least off the field, are run by their agencies, their managers and sponsors. I am afraid, even the most solemn of cricketing marriages and alliances these days are stage-managed for mileage and publicity by these PR managers. The ‘making hay while the sun shines’ predisposition has now trickled down to the Indian Premier League, where some of the players who haven’t even played first-class cricket look to make a fast buck. Nobody grudges them that moolah as long as it is through fair means. The Forbes list for the 100 highest paid athletes in the last year includes India skipper Virat Kohli. He is said to have grossed $22 million in 2017, i.e. R. 140 crore. He is the only cricketer in the list. A few years ago, MS Dhoni was there and before that there was Sachin Tendulkar too. Any cricketer, who plays all formats of the game and the IPL, even for a couple of years, is rich by Indian standards. In a land where the per capita income is around Rs 1.03 lakh, anybody with a net worth of Rs 30 to 40 crore would be considered to be prosperous. How many well-educated Indians can boast of such wealth at the end of a long corporate career? What’s more, for a player who is marketable and endorses dozens of products, the sky is the limit. Therefore, how much he earns through sponsorships, endorsements and ‘public appearances’, can only be a matter of conjecture. After the recent meeting between members of the CoA and Ravi Shastri, Kohli and Dhoni, it is believed that the annual contracts offered to Indian players would jump a 100 percent. Reliable sources tell me that some of cricket’s top celebrities, active and retired, demand as much as Rs 1 crore for making an appearance at showroom openings, product launches and even high-brow wedding receptions! The line dividing cricket and Bollywood has now been obliterated. Both are glamour jamborees and demand similar, star prerogatives and lifestyles. England’s cricketers get an equivalent of Rs 6 crore annually as retainers, while Australians are paid an equivalent of Rs 4.3 crore for the same period. Over and above this, they are paid match fees. Cricket salaries in both countries are up for revision and could see a substantial jump 2020 onwards. Once Indian cricketers’ annual contracts are revised, they won’t be badly off as compared to their English and Australian counterparts; especially when the cost-of-living index is taken into consideration. The cost-of-living index for Australia is 85.96, as compared to 76.02 in England and 67.50 in India. Now, let’s compare the amount of money that Indian cricketers make to what other star Indian sportspersons earn in a year. PV Sindhu, who won a silver medal at the Olympics in 2016, is said to have grossed Rs 18 crore from prize-money, awards and sponsorships in the last 12 months. According to sources, she has now signed a Rs 50 crore deal over three years, to endorse products. Sania Mirza and Saina Nehwal are said to have signed endorsement deals of around Rs. 16 crore each. Star footballer and India skipper, Sunil Chhetri earns something like Rs 60 lakh annually from match fees and was bought by his football franchise, last year, for Rs 1.2 crore. Indian hockey players earn much less. Sports minister Rajyavardhan Singh Rathore’s move to pay Rs 50,000 as a monthly stipend to more than 150 athletes who are preparing for the Asiad, the Commonwealth Games and the Olympics is therefore laudable. India will never be able to progress in international sport if our athletes can’t look after themselves and their families, and of course, aren’t able to afford special diets and training facilities. In a recent interview, former India skipper, Sourav Ganguly said that BCCI earns a lot of money and, therefore, players should be looked after well and paid handsomely. The BCCI will collect $2.55 billion for the IPL broadcast rights from Star Sports. There’s a bounty to be received from ICC and then, TV rights for the next few seasons is up for grabs. It is this money that has encouraged players to ask for their slice of the cake. ‘Money goes where money is,’ is an old adage. Ganguly is well within his rights as an ex-cricketer and administrator to push for salary reforms for international cricketers. So also are Shastri, Kohli and Dhoni. But what stops them from sparing a thought for and demanding a better deal for the country’s first-class cricketers? And what about the coaches and umpires who work tirelessly at the grassroots level or the curators and ground staff who are paid a pittance for their efforts? A couple of months ago, I was amazed by a ‘fun’ interview that Rohit Sharma did with newcomers Yuzvendra Chahal and Kuldeep Yadav on TV. When asked about their favourite cars, Chahal said, “Porsche” and Yadav said, “Ford Mustang – 1990s model.” This little conversation told me a lot about the level of confidence that an India cricket cap brings with it. Indian cricketers are indeed a pampered lot. To supporters of Indian cricket who believe that they have worked hard for it, I would like to ask, “Who hasn’t?” Ask a Sindhu or a Sania Mirza or a Sunil Chhetri, or even a Rajyavardhan Singh Rathore. Or for that matter, the cricketers of the 1970s-1990s who worked hard to make Indian cricket what it is today. The author is a caricaturist, sportswriter and mental toughness trainer. He was a fast bowler and Mumbai’s Ranji probable in the 1980s.

Austin Coutinho is a sportswriter and cartoonist based in Mumbai. Formerly a fast bowler who was a Ranji Trophy probable in the 1980s for the city, Coutinho retired as senior manager (CRM) from Rashtriya Chemicals & Fertilizers in December 2014. Coutinho was former president of the Mumbai District Football Association, a coaching committee member of the Mumbai Cricket Association, and a member of Maharashtra’s Sport Committee. A coach and mental trainer, he has mentored some top class cricketers and footballers. Coutinho has also authored 6 books on sport and has contributed articles, cartoons and quizzes to some of the best newspapers and sports portals in the country.

)