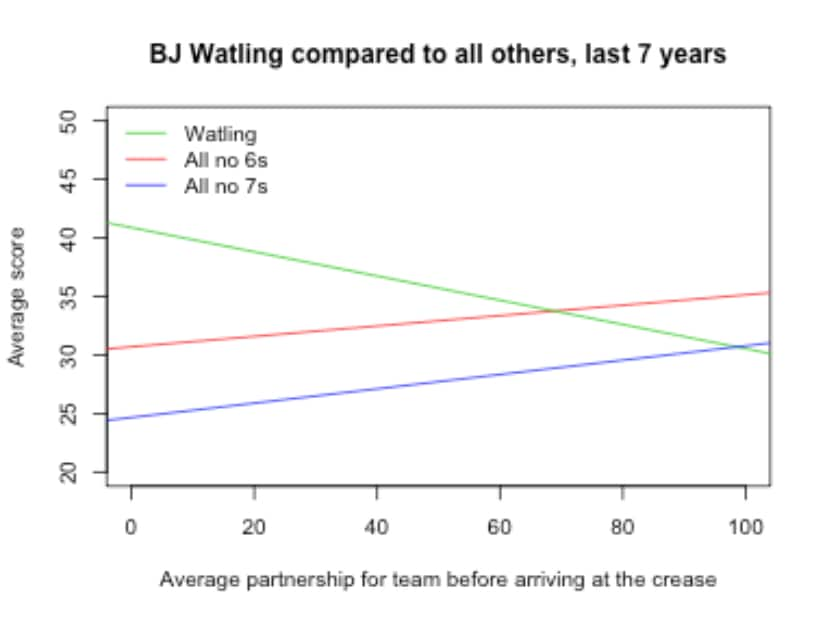

The drive from Durban to Klerksdorp takes about seven hours. To fly from Tauranga to Brisbane takes about eight hours. BJ Watling and Marnus Labuschagne have made their way from similar starting points to similar destinations, but through very different pathways. Watling was born in Durban, and went to an English-speaking primary school in the early 1990s, before, when he was 10 years old his family moved to New Zealand, and settled in the Waikato in New Zealand. They joined a large number of South Africans to make the trip. Just over one percent of New Zealand’s population was born in South Africa, with more immigrating to New Zealand regularly. About 60 percent of the South African immigrants live in Auckland, but nearby Waikato is also a popular place for them. Watling found himself at Hamilton Boys’ High School, a large all-boys school that has a very strong record in schoolboy sports. They have won the three most prestigious trophies (the Moascar Cup in rugby, the Gillette Cup in cricket and the Maardi Cup in rowing) on multiple occasions. It is one of the factories that produces top New Zealand sportsmen. [caption id=“attachment_7692931” align=“alignnone” width=“825”] Australia’s Marnus Labuschagne (L) went on score his maiden Test hundred against Pakistan in Brisbane, while playing eight hours away in Tauranga New Zealand’s BJ Watling hit his first-ever double century against England. AP[/caption] Watling was successful as a schoolboy cricketer, and made his first-class debut while he was still a teenager. He kept wickets in his first match, but was quickly asked to give up the gloves and focus on opening the batting. At about the time that Watling’s family was leaving South Africa, Marnus Labuschagne was born in Klerksdorp. While it is only a small drive from Durban, his experience was a world apart. Labuschane is from an Afrikaans-speaking family, and did not speak English when his family arrived in Australia, also at the age of 10. He went to school in Brisbane and, while he initially struggled with the language, he excelled with the cricket bat. In an apparent attempt to fit in, he even changed how he pronounced his name from the traditional Afrikaans “La-buh-skag-nee” to the more francophile “La-bou-shane”. He played lots of age-group cricket for Queensland, and, similarly to Watling, made his first-class debut just after his 20th birthday. Watling made his New Zealand debut at 25 in a T20I match, and surprisingly, was asked to keep wickets. It was a surprise, because he had only kept in a few domestic matches. But Watling was soon picked to open the batting in Tests, without being asked to take the gloves. He and Tim McIntosh created a solid partnership in terms of the defensive, but it was not particularly successful in terms of run scoring. He was soon passed up for other options, with an average in the 20s. But it was not long before the New Zealand management decided to give him another chance with the gloves. He did not disappoint. One of the things that he showed in his first match as keeper was his ability to come in when things were difficult, and settle things down. New Zealand had lost three quick wickets after a good start when Watling arrived at the crease. He took away the momentum, then attacked, batting with the tail to bring up his maiden century. This would become a pattern. Whenever New Zealand was in trouble, Watling would stand up. Most lower order batsmen do best after they have had a good rest, and get to bat against tired bowlers. For every extra 10 runs that a team averages per partnership before the number 6 or 7 gets to the crease, the number 6 or 7 batsman tends to score an extra one run (on average). Watling tends to do the opposite. He thrives in a crisis. The graph below shows expected score rather than batting average (runs per innings, rather than runs per dismissal) but the difference is clear. Watling is a step ahead of others when he comes in and the team is in difficulty, but is below average if he comes in when the going is good. [caption id=“attachment_7692741” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

Australia’s Marnus Labuschagne (L) went on score his maiden Test hundred against Pakistan in Brisbane, while playing eight hours away in Tauranga New Zealand’s BJ Watling hit his first-ever double century against England. AP[/caption] Watling was successful as a schoolboy cricketer, and made his first-class debut while he was still a teenager. He kept wickets in his first match, but was quickly asked to give up the gloves and focus on opening the batting. At about the time that Watling’s family was leaving South Africa, Marnus Labuschagne was born in Klerksdorp. While it is only a small drive from Durban, his experience was a world apart. Labuschane is from an Afrikaans-speaking family, and did not speak English when his family arrived in Australia, also at the age of 10. He went to school in Brisbane and, while he initially struggled with the language, he excelled with the cricket bat. In an apparent attempt to fit in, he even changed how he pronounced his name from the traditional Afrikaans “La-buh-skag-nee” to the more francophile “La-bou-shane”. He played lots of age-group cricket for Queensland, and, similarly to Watling, made his first-class debut just after his 20th birthday. Watling made his New Zealand debut at 25 in a T20I match, and surprisingly, was asked to keep wickets. It was a surprise, because he had only kept in a few domestic matches. But Watling was soon picked to open the batting in Tests, without being asked to take the gloves. He and Tim McIntosh created a solid partnership in terms of the defensive, but it was not particularly successful in terms of run scoring. He was soon passed up for other options, with an average in the 20s. But it was not long before the New Zealand management decided to give him another chance with the gloves. He did not disappoint. One of the things that he showed in his first match as keeper was his ability to come in when things were difficult, and settle things down. New Zealand had lost three quick wickets after a good start when Watling arrived at the crease. He took away the momentum, then attacked, batting with the tail to bring up his maiden century. This would become a pattern. Whenever New Zealand was in trouble, Watling would stand up. Most lower order batsmen do best after they have had a good rest, and get to bat against tired bowlers. For every extra 10 runs that a team averages per partnership before the number 6 or 7 gets to the crease, the number 6 or 7 batsman tends to score an extra one run (on average). Watling tends to do the opposite. He thrives in a crisis. The graph below shows expected score rather than batting average (runs per innings, rather than runs per dismissal) but the difference is clear. Watling is a step ahead of others when he comes in and the team is in difficulty, but is below average if he comes in when the going is good. [caption id=“attachment_7692741” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]

Watling tends to thrive in crisis.[/caption] Brendon McCullum once described Watling as his favourite cricketer, because he was so mentally strong. He felt that he played his best cricket when others were relying on him. There is a theory is that children who immigrate to another country get an opportunity to develop resilience that will last throughout the rest of their life. It is possible that Watling’s experience as a child who was uprooted from the familiar life on the coast in South Africa to go to the misty valleys of the Waikato basin in southern Polynesia helped create the instinct in him that kicked in when the team was in trouble. That same instinct also seems to be present in Marcus Labuschagne. He had looked like he belonged at the Test level in his first few performances, but did not really produce the results that demanded he keep his spot until the match where he was brought in as a concussion substitute for Steven Smith in England. A fired up Jofra Archer had just floored Smith and was keen to add another victim, but hitting Labuschagne just got him fired up. He scored 59, then followed that up with 74, 80 and 67 in consecutive innings. The only question left was if he could convert the fifties to hundreds. Against Pakistan, he answered that emphatically. His 185 was an innings where his mental strength came to the fore. He was untroubled by any attempt to unsettle him. Pace or spin it did not matter. He stayed within his game plan, playing the shots that he wanted to play, and playing them well. The innings, eight hours away in Tauranga, by BJ Watling is a similar exercise in mental strength. He came in with the Black Caps scoreboard reading 127 for 4, and New Zealand were in grave danger of conceding a sizeable first innings lead to England. Watling with his fighting instinct that he is so famous for came to the fore. He first put together a gritty 70-run partnership with Henry Nicholls, then was part of a 119-run stand with Colin de Grandhomme and a mammoth 261-run effort with Mitchell Santner. He brought up his double century just before Tea on Day 4, after coming in to bat just after Tea on Day 2. He was dismissed just after tea for 205. He perished trying to attack to set up a declaration, rather than just playing for a not out. It was pure Watling. Two players born fairly close together in one country, brought up in foreign lands and both developed the mental strength combined with technical skill to enable them to represent their adopted nations. Both scored big centuries on the same day, just a few hours travel apart.

Watling tends to thrive in crisis.[/caption] Brendon McCullum once described Watling as his favourite cricketer, because he was so mentally strong. He felt that he played his best cricket when others were relying on him. There is a theory is that children who immigrate to another country get an opportunity to develop resilience that will last throughout the rest of their life. It is possible that Watling’s experience as a child who was uprooted from the familiar life on the coast in South Africa to go to the misty valleys of the Waikato basin in southern Polynesia helped create the instinct in him that kicked in when the team was in trouble. That same instinct also seems to be present in Marcus Labuschagne. He had looked like he belonged at the Test level in his first few performances, but did not really produce the results that demanded he keep his spot until the match where he was brought in as a concussion substitute for Steven Smith in England. A fired up Jofra Archer had just floored Smith and was keen to add another victim, but hitting Labuschagne just got him fired up. He scored 59, then followed that up with 74, 80 and 67 in consecutive innings. The only question left was if he could convert the fifties to hundreds. Against Pakistan, he answered that emphatically. His 185 was an innings where his mental strength came to the fore. He was untroubled by any attempt to unsettle him. Pace or spin it did not matter. He stayed within his game plan, playing the shots that he wanted to play, and playing them well. The innings, eight hours away in Tauranga, by BJ Watling is a similar exercise in mental strength. He came in with the Black Caps scoreboard reading 127 for 4, and New Zealand were in grave danger of conceding a sizeable first innings lead to England. Watling with his fighting instinct that he is so famous for came to the fore. He first put together a gritty 70-run partnership with Henry Nicholls, then was part of a 119-run stand with Colin de Grandhomme and a mammoth 261-run effort with Mitchell Santner. He brought up his double century just before Tea on Day 4, after coming in to bat just after Tea on Day 2. He was dismissed just after tea for 205. He perished trying to attack to set up a declaration, rather than just playing for a not out. It was pure Watling. Two players born fairly close together in one country, brought up in foreign lands and both developed the mental strength combined with technical skill to enable them to represent their adopted nations. Both scored big centuries on the same day, just a few hours travel apart.

From being born a short trip apart in South Africa to a short trip apart in the antipodes, BJ Watling and Marnus Labuschagne share similar journey to Test success

Michael Wagener

• November 24, 2019, 10:30:52 IST

Two players born fairly close together in one country, brought up in foreign lands and both developed the mental strength combined with technical skill to enable them to represent their adopted nations. Both scored big centuries on the same day, just a few hours travel apart.

Advertisement

)

End of Article