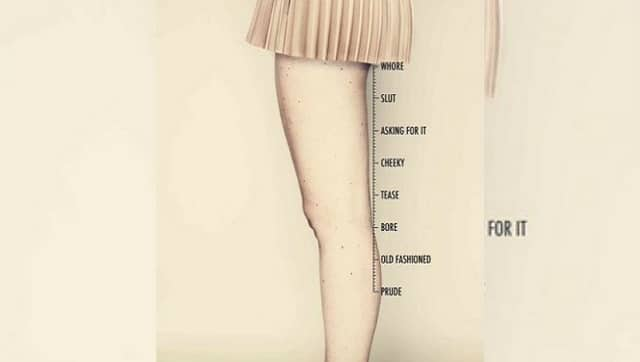

‘Curious Fashion’ is a monthly column by feminist researcher, writer and activist Manjima Bhattacharjya. Read more from the series here . *** I’m trying to remember what I wore to the court martial appearances for a sexual harassment case I’d filed in 1998 against an army jawan who had molested me on a train journey from Ranchi to New Delhi. Much as I try, I don’t remember. I do remember what I was wearing when I was assaulted, though. I’m sure many women do. It was an onion-pink, thick, twill salwar suit from Sarojini Nagar. Several fabulous initiatives exist that gather what women were wearing when assaulted, to challenge the myth that women ‘ask for it’ by wearing ‘provocative’ clothes. Repeatedly, the evidence has shown there’s no correlation between what women wear and their being assaulted. The Blank Noise Project (where I considered sending the aforementioned salwar suit) has clothing items from churidaars, to kurtis and jeans, to girls’ frocks and burkhas. The ‘ What Were You Wearing’ exhibit has pieces ranging from a bikini to a young boy’s collared shirt. Yet this perception remains. [caption id=“attachment_8279871” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Repeatedly, the evidence has shown there’s no correlation between what women wear and their being assaulted. Yet this perception remains. Artwork by Terre-des-femmes. Twitter/@theSA_brand[/caption] But this column is about what happens next. What do women wear to court when they go as accusers, the accused or as witnesses, to testify? A few things got me thinking about this. First was the drama surrounding the case of Anna Sorokin alias Anna Delvey, the fascinating story of a Russian-born New York socialite convicted of defrauding people by pretending to be a German heiress. The New York Post wrote of the Sorokin legal team’s wardrobe panic when she was brought to court in her prison outfit. Her defense lawyer, fearing this might make her “look guilty”, rushed an associate to H&M to get her “something that didn’t scream ‘inmate’". Then came an Instagram account documenting her court looks, and articles on the appointment of a specialised “ courtroom stylist” for Sorokin. Because, as her lawyer stated, “Anna’s style was a driving force in her business, and life, and it is a part of who she is. I want the jury to see that side of her.”

What a woman wears to court is telling of how clothes communicate in court, but does it influence the court’s judgement?

It might. A study in the UK found that women victims of sexual assault who cover their head or face in hijab or niqab are viewed as more credible witnesses. A reminder that the judge and jury are human, with biases based on social norms and moral frameworks that are so hard to shake off. Hyperaware fashioning of the self in court underlines, and uses, this fact. When I spoke to feminist and human rights lawyer Vrinda Grover about this, she told me an interesting anecdote from the late 80s of two cases where women were accused of murdering their husbands, in conspiracy with their lovers (in one case, in a particularly gruesome manner). Grover recalls how the women would come from jail to the trial court dressed very demurely, either in white or pale-coloured salwar suits. They presented themselves as “respectable women”, even culturally-appropriate widows in mourning. It was hard to imagine them having made any social transgressions, forget adultery and murder. “When one of them came out on bail and visited me,” Grover says, “I was pleasantly surprised to see her dressed in modern Western clothes, rather different from her image in court!” An image they’d created for their trial quite on their own, without anybody having asked them to do it. In a similar case, an American trial lawyer writes of his experience on Quora: “When I clerked for the public defender’s office I worked on a pretty horrific death penalty case. I recommended that we dress the defendant in a V-neck sweater and white tennis shoes, reasoning that no jury would send a man in a V-neck and tennies to the gas chamber (this was back in the preppie 1980s). Sure enough, he was spared the death penalty, which I attributed to my shrewd fashion sense.” As Grover remarks, “Isn’t the Court a site of performance, where like in theatre, everyone is in costume. So are the lawyers. Everyone is dressed for their role, whether accused or complainant.” [caption id=“attachment_8279841” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  One of the outfits Anna Delvey wore to court. Instagram/annadelveycourtlooks[/caption] Court is also seen to be a sacred space, which is why fashion policing literally seems to be on the rise there. The Bombay High Court imposed a dress code asking those entering court premises to dress modestly, as did the Himachal Pradesh High Court more recently. A court in Georgia turned away people who were wearing tank tops on a hot day, or made them wear coats. Courts in Dubai now actually have a coat-lending service for women. A piece in the Harvard Law Review suggests these dress codes are sexist, classist and even unconstitutional, as they prohibit free entry into courthouses and exclude several kinds of people – the poor, marginalised, those who cannot or do not dress as per white corporate cultures. Courts, after all, are for public access, not a sanctum sanctorum. There is an added burden for women when it comes to cases of sexual harassment or sexual violence. The maximum conversation online on how women should dress for court revolves around such cases. No tight clothes, no cleavage, no midriff — feminine but prim clothes, of neutral colour. In New Zealand, a victim of child sexual assault was cautioned not to wear a short skirt or “too much” jewellery and make up in case she was perceived as promiscuous. Some law firms have clear guidelines about this. “Don’t wear anything you’d wear out on a Saturday night!” says this directive from a New York firm. Instead, wear what you’d hopefully be wearing on a Sunday morning – to church.

Women accusers of sexual assault face extreme scrutiny because of what people believe a perfect victim should look like.

A woman about to testify in her rape trial shares the detailed response from her legal team that acknowledges, “how tough a balancing act dressing for court can be”. You are a victim, but you want to look in control, serious and most importantly, credible. For writer Eva Harberg Fisher, deciding what to wear to trial after filing a sexual harassment complaint against one of her professors was a lesson in “ how to look believable”. The message is this: Even if you’re not the one on the stand being judged, you have to prove yourself ‘innocent’ to be heard. If you dress like a ‘good girl’ — submissive, feminine, asexual, obedient — your chances of this are higher. Dress like a ‘slut’ and you’re guilty already — of dressing like a slut, if nothing else. Women participate in this charade, intuitively knowing these extra-legal parameters against which they will be judged. In India too, Grover agrees that in sexual assault cases, what women wear when they step into the witness box to testify does matter, at least subliminally. It’s a conversation “often initiated by the woman herself who is unfamiliar with court practices.” But Grover feels there’s a marked change from the 80s to now in trial courts in Delhi, where she practices. One reason for the change is the presence of many more young women lawyers practicing in courts these days. “I only wear sarees to court," she says, “but younger women lawyers wear trousers, and it is no longer seen as immodest or disrespectful.” Although this may be specific to Delhi, Grover feels the norms around court dressing for women have eased up, with the kurti-trouser look now quite common. “Women victims or witnesses will not wear flashy revealing clothes to court,” she notes, “but they are definitely not appearing in court in a saree or with their head covered with a dupatta." It’s significant when Grover says, “We are also no longer seeking justice for the woman by presenting her as ‘a good woman’ abiding by conservative or orthodox norms.” Nowadays in sexual assault cases quite often the accused is a friend, or someone known to the victim, or in a relationship with her. Her testimony often details this relationship. “We are compelling the court to comprehend this complex reality of sexual violence, and for this, the woman dresses in her usual apparel when she steps into the witness box,” says Grover. What a relief, I say. This might be a game-changer. We may no longer be forced to fashion ourselves as ‘good girls’ in the hope that this will help us find justice. High time we separated a woman’s ‘character’ from her clothing, in court or otherwise. Remember that when you’re dressing for your next court appearance. Manjima Bhattacharjya is the author of Mannequin: Working Women in India’s Glamour Industry (Zubaan, 2018)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)