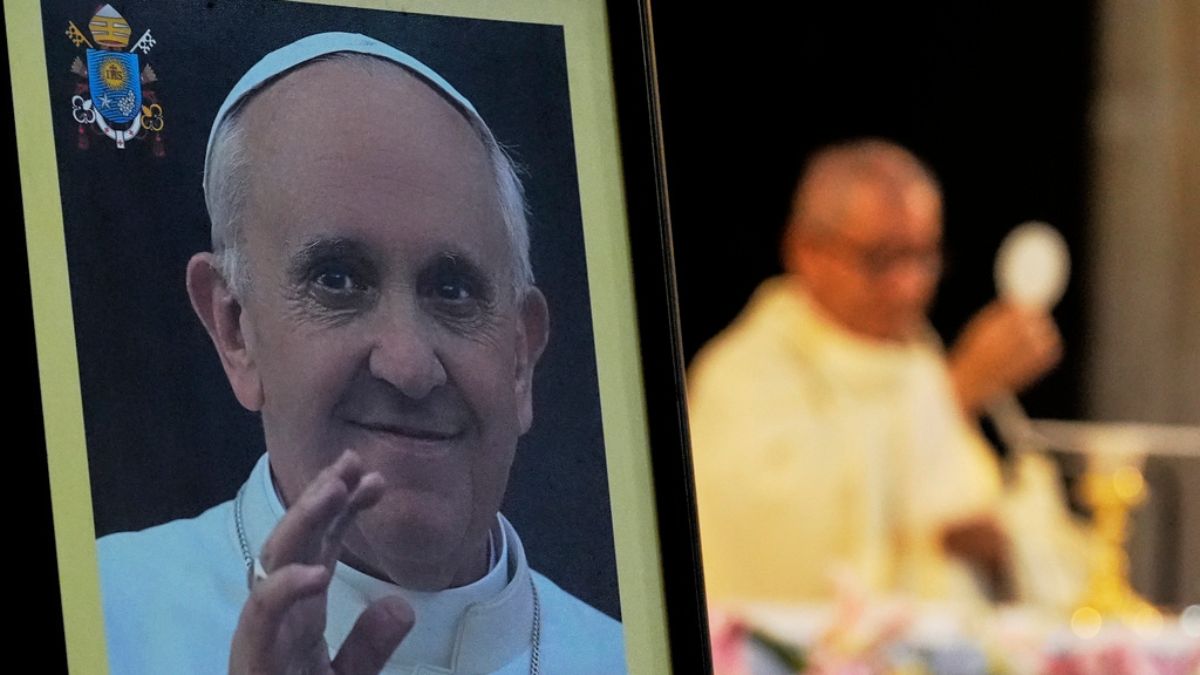

Pope Francis was born Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Buenos Aires.

In 2013, Francis ascended to the Chair of St Peter.

But despite being the first pope from Latin America, Francis never once returned home to Argentina.

The decision left many who knew Francis during his stint as Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio of Buenos Aires perplexed.

But why did Francis never visit Argentina?

Let’s take a closer look:

Political factors at play

According to Vatican insiders, Francis rarely spoke of his decision not to visit Argentina.

But those that knew the late Pontiff said he wanted to avoid becoming part of its volatile political scene.

“It’s sad, because we should have been proud to have an Argentine pope,” said Ardina Aragon, 94, a long-time friend and neighbour of Francis said.

Aragon hails from the middle-class neighborhood of Flores where Francis was born in 1936.

“I think there were political factors that influenced him.”

Francis , who loved soccer, tango and other aspects of Argentine culture, was known to have fraught relationships with some of his country’s leaders.

His ideological issues with far-right President Javier Milei, who took office in 2023, complicated things even further.

Popularity at home wanes

Argentina celebrated Francis becoming Pope with an ecstasy otherwise reserved for the country’s three World Cup soccer championships.

But that initial excitement over the former archbishop of Buenos Aires becoming Pope gave way over the years to a more jaded outlook.

A recent Pew Research Center report showed that Francis’ popularity had dropped more in Argentina than anywhere else in the region over the last decade. About 64 per cent of respondents said they had a positive view of Francis in September 2024, compared with 91 per cent in 2014.

“There are many among us who think he made mistakes. Not everyone in our community is proud of the association,” said Adriana Lombardi, 62, a retired teacher in Buenos Aires, referring to traditionalist Catholics in Argentina and beyond who accused Francis of leading the Church astray.

Some in Buenos Aires felt slighted by Francis’ avoidance of Argentina.

“Despite his history here, it seems like he doesn’t care about us,” said Bruno Rentería, 19, who was praying in front of an icon of the Virgin Mary at the Basilica of San Jose de Flores in Buenos Aires. Older churchgoers recalled the very confessional where Bergoglio, at age 16, had first heard the call to the priesthood. “It’s odd because it seems like he has time for everyone else.”

Archbishop of Buenos Aires

Some trace those tensions to when he was archbishop of Buenos Aires during the leftist tenures of the late former president Néstor Kirchner and his successor and wife, the divisive Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, whose strain of populism dominated Argentine politics for decades.

Francis and Fernández de Kirchner were unfriendly neighbours in Plaza de Mayo, the central square that hosts both the government headquarters and the cathedral where Francis delivered homilies during much of her presidency from 2007-15.

From the pulpit, Francis criticised the “exhibitionism” and autocratic tendencies of Argentina’s political class — a subtle dig that the Kirchners interpreted as a direct attack. His support for the Vatican’s conservative positions on key social issues deepened rifts with Fernández de Kirchner’s progressive government as it expanded sex education and, in 2010, legalised same-sex marriage — a first for Latin America.

Perhaps most significantly, supporters of the Kirchners accused Francis of complicity in Argentina’s 1976-83 military dictatorship, when as many as 30,000 people were estimated by human rights groups to have been killed or simply “disappeared.”

Francis was head of Argentina’s Jesuit order during those violent years, when the junta targeted radical clerics and priests who worked with the poor.

Francis rejected the accusations of complicity. In his 2024 memoir, “Life: My Story Through History,” he recalled hiding wanted activists and pressing military officials behind the scenes to free two abducted priests from his order.

Eventually, Kirchner’s social welfare policies resonated with Bergoglio. The two drew closer after he became pontiff and set about softening the image of an institution that had long seemed forbidding.

“Conservatives in Argentina failed to understand his change of attitude,” said Sergio Berensztein, who runs a political consultancy in Buenos Aires.

The ‘Peronist Pope’

Unsettled by his critiques of the excesses of capitalism, right-wing critics branded Francis the “Peronist Pope” — a reference to the Argentine populist movement founded by three-time President Juan Domingo Perón, who employed an authoritarian hand and powerful state to champion social justice causes.

From that point on, Berensztein said, Francis “felt everything he said or did would lead to fighting on either side of the divide.”

Francis’ politics came under more scrutiny in 2016, when he wore an unusually grim expression while posing for a photo beside former president Mauricio Macri, Kirchner’s conservative successor, whose austerity program battered the poor.

The awkward photo-op paled in comparison to Francis’ discomfort with what followed.

President Milei, a former TV pundit and corporate economist, called Francis an “imbecile” and “the representative of the Evil One on Earth” before coming to power in 2023.

He lashed out at the pope for promoting social justice, supporting taxes and sympathising with “murderous communists.”

Francis expressed sympathy for the strife of Argentines pulled into poverty as they bore the brunt of Milei’s fiscal shock therapy, voicing concern over his radical libertarian views and criticizing Argentine security forces for using pepper spray and tear gas against Argentine retirees protesting for better pensions.

The Vatican described a meeting between Francis and Milei in 2024 as “cordial,” but ideological differences resurfaced with the ascension of Milei’s political ally, US President Donald Trump.

Since Trump’s reelection, Francis has intensified direct attacks on the administration, criticising its mass deportation of migrants and other policies.

“Francis cultivated a social doctrine in the church that generated opposition, particularly among conservatives in the United States,” said Sergio Rubin, an Argentine journalist and Francis’ authorized biographer.

‘Pains me’

After a dozen years of papal travel — including to nearly all Argentina’s neighbors — Francis referenced a plan to visit his native land last year. Nothing came of it.

“He went to Brazil, Peru, Chile; he passed over our heads,” said Lucia Vidal, a retired nurse who attended Bergoglio’s Mass when he was archbishop. “That pains me.”

In contrast, Pope John Paul II visited his native Poland less than a year after becoming pontiff in 1978. His successor, Pope Benedict XVI, chose his native Germany for his first foreign trip in 2005.

Other Argentines seemed less indignant about the snub and more grateful for his contributions to the impoverished neighbourhoods of Buenos Aires, where Bergoglio first earned fame as the “slum bishop,” leading processions, creating a cadre of priests who follow in his footsteps and founding shelters for homeless addicts and community centers on violence-scarred streets.

“I can’t express what his humility, his open hands, meant to me, my family, my neighbourhood,” said Angela Cano, 51, at a Mass held in his honor Monday at Villa 21-24, a neglected suburb near the railroad. “We saw up close how he was the pope of the people. He helped us find God.”

Back in Flores, Carlos Liva, 66, a retired cab driver, said he couldn’t begrudge the pope for prioritising the rest of the world after spending most of his years in Argentina.

“It’s clear that he felt at ease in Rome,” Liva said. “In his own country, people found every reason to question him.”

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)