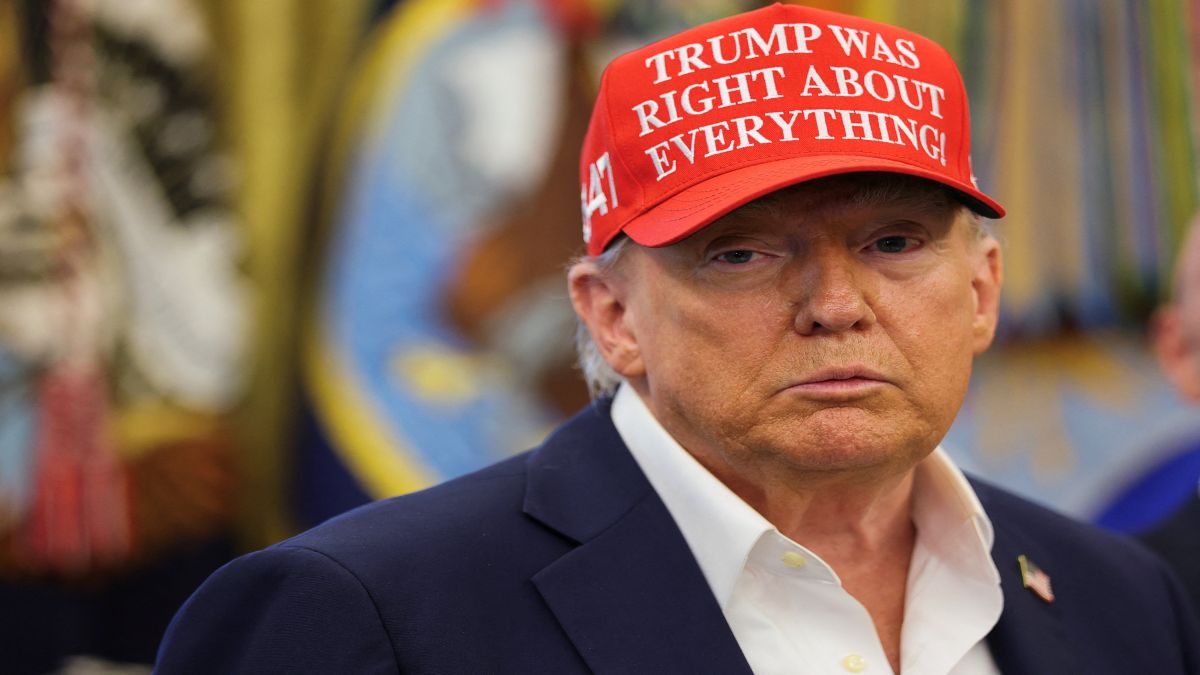

US President Donald Trump has targeted India over the trade deficit with the United States yet again.

Trade deficits have emerged as something of a bugbear for Trump. His obsession with them, which began during his first term, has seemingly reached new heights this year.

Trump in April announced his ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs, in a move that rattled trading partners and temporarily shook the world economy.

Data show that the United States in 2025 imported goods worth $56.3 billion from India , while New Delhi imported goods worth $22.1 billion from Washington. India thus has a trade surplus of $34.3 billion with the United States this year.

However, did you know that the United States secretly mints billions from its trade relationship with India?

Analysis from the Global Trade Research Initiative (GTRI) shows that the US actually is at a $35–40 billion surplus with India when certain revenue streams are counted.

The GTRI says this is because of ’non-merchandise income’ that standard trade calculations fail to take into account.

This comprises earnings from education, digital services, financial and consulting operations, intellectual property licensing, arms deals and entertainment.

“These massive earnings don’t show up in the narrow goods trade statistics. When you factor them in, the US isn’t running a deficit with India at all — it’s sitting on a $35–40 billion surplus,” Ajay Srivastava, founder of GTRI, explained.

US is actually at a surplus

As per GTRI’s estimates, the US takes in between $80-$85 billion each year from India through several revenue channels not listed in the bilateral goods trade balance.

Among the largest contributors to America’s kitty comes from the higher education sector. Indian students studying in the United States spend a total of over $25 billion annually — around $15 billion in tuition fees and another $10 billion in living expenses.

These students attend leading universities such as the University of Southern California, New York University, Purdue University and Northeastern. Their average yearly expenses range from $87,000 (₹76 lakh) to $142,000 (₹1.25 crore) per student. This education-related expense makes higher education one of America’s biggest “exports”, though it does not register in conventional goods trade figures.

When it comes to technology, US digital giants such as Google, Meta, Amazon, Apple and Microsoft reportedly generate $15–20 billion in yearly revenues from India through various services.

These include cloud storage, digital advertisements, app store sales, subscription models and software services. These substantial earnings are further increased by what GTRI refers to as “limited local rules on data and taxation” — which allows the tech giants take most of their earnings back to the United States.

The US also earns $10–15 billion in annual revenue through investment banking, financial advisory, and consulting services in India. Firms such as JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs, Citibank, McKinsey, Deloitte, KPMG and PwC operate across India’s growing financial and corporate ecosystem, advising on mergers and acquisitions, risk management and business transformation.

From pharma to Hollywood: the overlooked value chains

Intellectual property and licensing comprises another major but less visible source of income. US pharmaceutical firms including major players such Pfizer, Merck and Johnson & Johnson gross around $1.5–$2 billion each year via licensing agreements, patent royalties and technology transfers with Indian partners.

Meanwhile, US automobile companies, including General Motors and Ford, make between $800 million and $1.2 billion annually through technical service fees and licensing deals with Indian auto manufacturers and component suppliers.

Then you have culture and media with Hollywood studios and American streaming platforms — such as Netflix, Amazon Prime and Disney — are estimated to earn $1–$1.5 billion annually from India.

These earnings arise via box office revenues, content licensing and growing subscription-based digital platforms targeting Indian consumers.

Global Capability Centres (GCCs) & Defence

A major but frequently ignored component of the US’ economic footprint in India is the vast network of Global Capability Centres (GCCs) operated by American multinationals. Companies such as Walmart, Dell, IBM, Wells Fargo, Cisco and Morgan Stanley run these centres in Indian cities like Bengaluru and Hyderabad.

While they employ thousands of Indian professionals in fields such as analytics, technology development and operations, the real economic value is often recorded back in the US, rather than in India.

According to GTRI, these GCCs generate $15 – 20 billion annually from India-based operations, most of which accrues to the US parent entities.” These earnings, again, are not factored into bilateral trade deficit figures, even though they represent a substantial inflow of value to the American economy.

In addition to the economic sectors mentioned above, defence exports represent another substantial but confidential component of US earnings from India. While specific numbers remain classified, the cumulative value of American arms deals and technology transfers to India has run into billions over the past decade.

This includes fighter aircraft, helicopters, surveillance systems, and missiles — many of which are secured under the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) programme and other government-to-government channels.

What the facts say

Despite this deep commercial engagement, the US continues to demand further concessions from India in upcoming trade negotiations.

Trump has repeatedly claimed a $100 billion trade deficit with India, although official data puts it at under $34 billion for 2025.

As GTRI rightly pointed out, the deficit narrative doesn’t capture the full picture of value exchange between the two countries.

“Far from being a victim in the relationship, the US is a top beneficiary,” Srivastava said.

“If the US insists on focusing solely on the trade deficit, then India should narrow the conversation strictly to tariff cuts — and firmly refuse to entertain talks on government procurement, digital trade, intellectual property and the many other areas where US firms stand to massively expand their profits inside India.”

Negotiating from a position of strength

The GTRI report urges Indian negotiators to push back against “hollow deficit arguments” and to resist pressure to make unilateral concessions in areas like digital trade, intellectual property rights, and market access — areas where American companies are already dominant earners.

“India is not just a passive trade partner but a major contributor to American wealth across education, technology, finance, and defence,” Srivastava pointed out.

“India can and should negotiate the free trade agreement from a position of strength — rejecting hollow deficit arguments and demanding fair, balanced, and reciprocal terms.”

Also Watch:

With inputs from agencies

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)