The first G20 leaders’ summit to take place in Africa is already missing a major member as it kicks off in Johannesburg, South Africa on November 22-23, 2025.

President Donald Trump has opted to exclude the United States entirely from the summit, marking the first time in the group’s 26-year existence that a member state has not only avoided sending its head of government but has refused to participate at any level.

The move, rooted in Trump’s long-running allegations concerning the treatment of white Afrikaners in South Africa, has disrupted months of negotiations, at a moment when developing nations hoped to place their priorities at the forefront of the annual summit.

Why the US withdrawal from G20 summit is unprecedented

The G20 has weathered disagreements among its members before, but never has a participating country entirely vacated its seat.

Trump’s order prevents all officials — not just Cabinet-level figures — from attending discussions, workshops, or negotiating sessions.

South Africa, as this year’s chair, was informed of the decision through formal diplomatic channels, and other G20 governments were subsequently notified that the United States would be absent from the meeting in its entirety.

The boycott is especially striking because the United States is next in line to assume the rotating presidency of the club.

Under normal circumstances, the leader of the incoming host nation participates in the preceding summit to ensure a smooth transition, coordinate multi-year agenda items, and signal continuity.

This year, however, Trump has declined to travel, cancelled earlier plans to dispatch Vice President JD Vance, and instructed all federal agencies to avoid participating.

Only a representative from the US Embassy in Pretoria will attend the closing ceremonial exchange, as it is a formality that cannot legally be skipped.

Diplomats involved in preparing the summit say the absence of the US delegation has derailed efforts to craft a shared outcome document. Numerous G20 norms rely on unanimous agreement, and even minor wording typically requires negotiations.

One senior European diplomat involved in the lead-up told the Financial Times, “It’s bleak… There’s really nothing that we can hope to achieve without the Americans engaging.”

Another official expressed exasperation that the boycott had derailed what already promised to be a challenging round of talks, saying, “We knew Trump hates this kind of thing but it’s one thing to be difficult, and another to completely blow it up.”

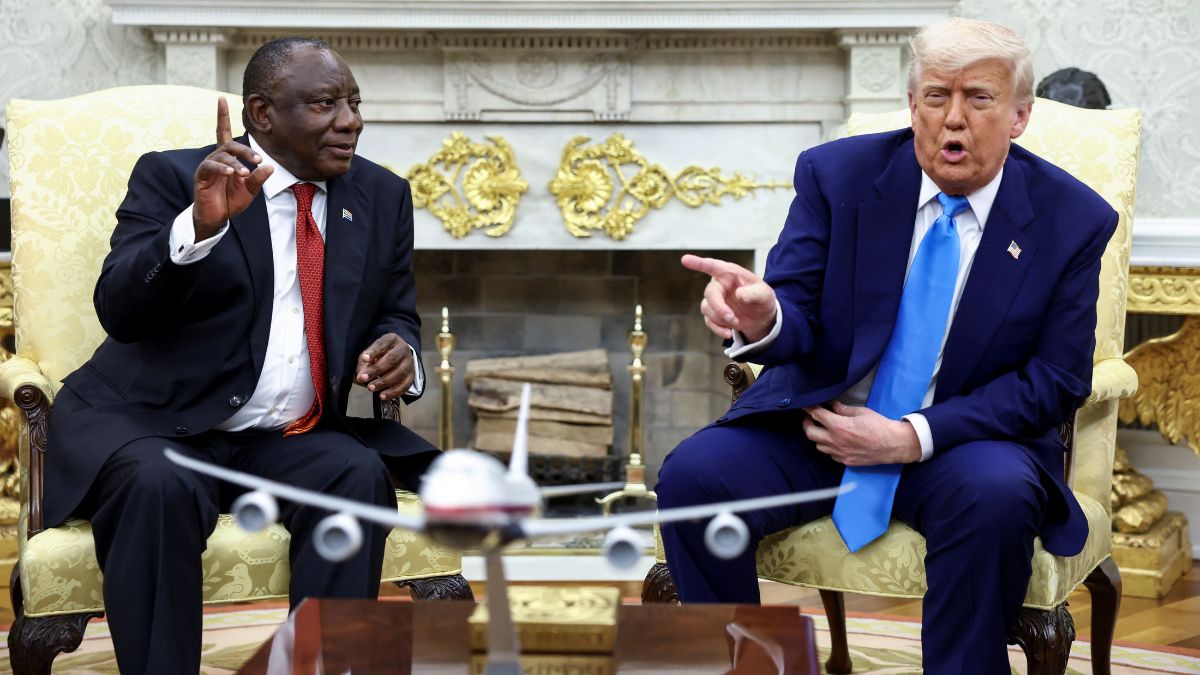

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa publicly criticised the withdrawal, remarking, “If you boycott an event or a process, you are the greatest loser because the show will go on.”

He added that he planned to follow protocol nonetheless.

“I don’t want to hand over to an empty chair, but the empty chair will be there.” Ramaphosa said he would complete the symbolic handover of the presidency before later speaking privately with Trump.

South African Foreign Minister Ronald Lamola echoed the stance that the summit must proceed regardless of Washington’s choices.

He argued that most international forums continue even when some leaders cannot participate, insisting, “It is important that a declaration must be adopted by the countries that are present, because the institution cannot be bogged down by someone’s [absence].”

South Africa is still hoping that a communique or partial statement can be endorsed by the members who attend.

Why Trump says he is boycotting

Trump has tied his decision to his belief that South Africa is discriminating against white Afrikaners, particularly farmers.

He claims that white landowners are being attacked and dispossessed at alarming rates, and that the South African government is encouraging or allowing racial targeting.

Trump has stated publicly that white Afrikaners are being “slaughtered” and that their property is being seized.

He has repeatedly insisted the country is unsafe for them, and earlier this year, he began offering refugee status to Afrikaners who wish to leave. The first group — 59 individuals — arrived in the United States in May.

These claims, however, have been flatly rejected by South Africa and by many Afrikaners themselves.

Security data released by the South African Police Service, statements from government officials, and independent investigations have concluded that farm-related crimes are not targeted solely at white farmers and that violent incidents on rural properties remain a small portion of overall crime in the country.

In the first quarter of this year, six murders took place on farms; five of the victims were Black and one was white.

Officials have stressed that these crimes should be seen in the broader context of South Africa’s high rates of violent crime, which disproportionately affect Black citizens.

Earlier this year, the South African police minister described public narratives around farm attacks as historically being “distorted and reported in an unbalanced way.”

Many Afrikaners have rejected claims of racial victimhood. A group of Afrikaner journalists, academics and civil society members released a public statement arguing that they did not believe they were facing systematic persecution.

They wrote that they rejected the idea that they were “victims of racial persecution in post-apartheid South Africa” and objected to becoming “pawns” in foreign political debates.

Groups such as AfriForum, a right-wing lobby in South Africa, have nevertheless criticised the government’s new land expropriation law, which updates an apartheid-era statute. Critics contend it could open the door to land seizures without compensation.

The legislation only allows uncompensated expropriation in specific scenarios — for instance, when land is unused or abandoned — and only after negotiations with owners have failed.

Most large commercial farms remain under white ownership despite white citizens comprising roughly 8 per cent of the population.

Trump’s boycott has largely been interpreted abroad not as a reaction to new developments but as an extension of a narrative he has championed since early in his current term.

His administration has repeatedly signalled mistrust of South Africa’s political alignment with Russia, China and Iran, and has portrayed the country as unfriendly to US interests.

Who else is missing from G20 South Africa

The US boycott is the most consequential absence, but it is not the only one.

Chinese President Xi Jinping, who has reduced his international travel schedule, is not attending, though China has dispatched Premier Li Qiang to lead its delegation.

Russia’s delegation is also being led by lower-ranking officials due to the International Criminal Court warrant for President Vladimir Putin, which obliges South Africa — an ICC member — to detain him if he arrives on its territory.

Russia’s representative is Maxim Oreshkin, deputy chief of staff in the presidential executive office.

Argentina’s President Javier Milei has also chosen to stay away, citing his close political alignment with Trump.

Other leaders — including Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, France’s Emmanuel Macron, Germany’s Friedrich Merz and Britain’s Keir Starmer — are attending as planned.

The absences have left South Africa’s government confronting a summit that looks very different from the one it envisioned.

Ramaphosa had hoped the event would showcase Africa’s growing relevance in global affairs and strengthen the continent’s voice at the international table. Instead, the focus has shifted to the implications of the US decision.

What South Africa intended to showcase at the G20

This year’s host aimed to use the summit to highlight issues faced by developing nations, drawing on its position as both an economic anchor on the continent and a representative of lower- and middle-income countries. South Africa’s priorities include:

Strengthening support for nations dealing with climate disasters

Improving access to financing for green energy transitions

Expanding international programs to help countries contending with escalating debt burdens

Addressing disparities in global wealth distribution

South African officials argue that climate-related catastrophes — such as droughts, floods, cyclones and heatwaves — have created enormous economic pressures on countries with limited resources to rebuild.

Pretoria has pushed for more substantial commitments from wealthier economies in disaster relief and sustainable development.

South Africa also commissioned a report led by Nobel laureate and American economist Joseph Stiglitz.

The research concluded that the planet is confronting an “inequality emergency,” describing widening gaps in income and wealth that risk destabilising societies.

In response, South Africa has suggested forming an independent international commission to examine global inequality, modelled on the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Alongside these priorities, the summit is a traditional venue for bilateral meetings between leaders. Discussions were expected to address new trade negotiations, particularly in light of the Trump administration’s recent tariffs that have reshaped global commerce.

Civil society organizations, as in past G20 cycles, have organised parallel meetings and demonstrations. One counter-summit held in Johannesburg criticised what activists described as “a global economic system rigged in favour of elites and billionaires.”

Why this boycott by Trump & Co. matters

The G20 brings together 19 countries plus the European Union; the African Union joined as a permanent member in 2023 during India’s G20 presidency.

Its membership includes major economies from every region, ranging from the world’s largest industrialised nations to key developing states.

Unlike the G7, which focuses primarily on wealthy democracies, the G20 functions as a bridge between high-income and emerging economies, giving developing nations a platform to raise concerns and influence global policy discussions.

The forum was established in 1999 to improve cooperation on international economic issues, especially after the financial disruptions of the late 1990s.

The group does not have a permanent headquarters or binding enforcement powers.

Instead, it relies on collective political will and annual summits hosted by rotating presidencies.

Participants typically include leaders of member nations as well as heads of the United Nations, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

Yet the organisation often struggles to reach full agreement due to competing interests among its most influential members.

Tensions involving the United States, China and Russia frequently shape negotiations, while disagreements between major European powers and developing states add further strain.

Even under ordinary circumstances, drafting joint declarations can be a lengthy process.

Now, with the withdrawal of the entire US delegation, negotiators expect that no consensus-based statement can be produced.

For South Africa, the moment is bittersweet. Hosting the summit is symbolically important, especially as African nations push for stronger representation across global institutions.

With the handover of the presidency to the United States scheduled for the end of the summit, the future direction of the G20 is unclear.

Trump has already criticised the forum, saying it has “become basically the G100,” and has pledged that meetings during the US term next year will be more streamlined.

With inputs from agencies

)