For the first time ever, scientists have managed to capture clear images of the Sun’s north and south poles.

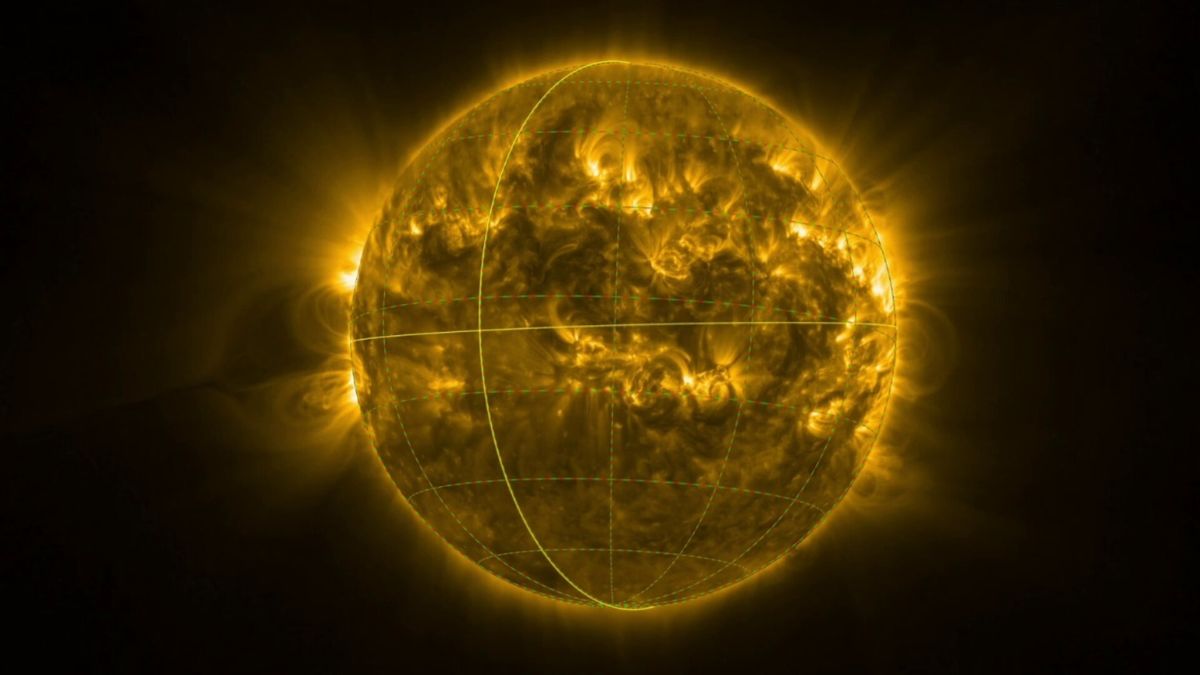

On Wednesday, the European Space Agency (ESA) shared photos taken in March by three instruments aboard the Solar Orbiter. These images show the Sun’s south pole from a distance of about 40 million miles (around 65 million kilometres).

Notably, Solar Orbiter was launched in 2020 from Florida. It is a joint mission between ESA and the American space agency, Nasa.

ALSO READ | 2 delays in 2 days: What’s happening with Shubhanshu Shukla’s Axiom-4 mission?

These latest pictures could help experts understand how the Sun shifts between calm phases and violent solar storms.

But why does this matter? What do the images actually reveal? And how will they support future research?

We will answer these questions in the explainer.

First-ever images of Sun’s poles revealed

Until now, all views of the Sun have come from a single angle, looking straight at its equator from the same plane where Earth and most other planets orbit, known as the ecliptic plane.

But in February, Solar Orbiter performed a slingshot manoeuvre around Venus, helping it move out of that plane and view the Sun from around 17 degrees below the solar equator. More such flybys are planned in future, which could allow views from more than 30 degrees.

On Wednesday, the European Space Agency released images taken in March using three instruments onboard the Solar Orbiter.

These images show the Sun’s south pole from a distance of around 40 million miles (65 million kilometres), captured during a period of peak solar activity. Images of the north pole are still being sent back by the spacecraft.

Impact Shorts

More ShortsProf Carole Mundell, Director of Science at ESA, said, “Today we reveal humankind’s first-ever views of the Sun’s pole.

The Sun is our nearest star, giver of life and potential disruptor of modern space and ground power systems, so it is imperative that we understand how it works and learn to predict its behaviour. These new unique views from our Solar Orbiter mission are the beginning of a new era of solar science.”

According to Prof. Mundell, these are the closest and most detailed images ever taken of the Sun, and they will help researchers better understand how our star functions.

ALSO READ | Soviet-era spacecraft likely to crash back to Earth this week: Should you be worried?

Explained: Why these images matter

The Sun is huge, about 865,000 miles (1.4 million kilometres) across, making it over 100 times wider than Earth.

Hamish Reid, a solar physicist at University College London’s Mullard Space Science Laboratory and UK co-lead for the Solar Orbiter’s Extreme Ultraviolet Imager, told Reuters that while Earth has clear north and south poles, the Solar Orbiter has detected both polarities of magnetic fields currently present at the Sun’s south pole.

“The data that Solar Orbiter obtains during the coming years will help modellers in predicting the solar cycle. This is important for us on Earth because the sun’s activity causes solar flares and coronal mass ejections, which can result in radio communication blackouts, destabilise our power grids, but also drive the sensational auroras,” he said.

Lucie Green from University College London, who was involved in developing the Solar Orbiter, told New Scientist that studying magnetic fields at the Sun’s south pole could improve our understanding of the solar cycle. This cycle tends to rise and fall in intensity roughly every 11 years.

🌞 See the Sun from a whole new angle.

— European Space Agency (@esa) June 11, 2025

For the first time, our Solar Orbiter mission has captured close-up images of the Sun’s mysterious poles, regions long hidden from our view.

In 2025, Solar Orbiter gave us a first-ever look at the Sun’s south pole.

Remarkably, it… pic.twitter.com/EhyYxtDyaR

Notably, scientists already know that the Sun enters a calm phase when its magnetic fields are well organised, with set north and south poles.

During this time, the Sun is less likely to erupt violently. But as the poles switch places every 11 years, the magnetic fields become more tangled and unstable.

This turbulent phase causes the Sun to try and settle the disorder, leading to solar storms, with fragments of the Sun being flung towards Earth. These storms can interfere with satellites and electricity grids, though they also trigger stunning auroras in the sky.

The Solar Orbiter has also captured some images of the Sun’s north pole, but ESA is still waiting for the data to be sent back to Earth.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)