United States President Donald Trump’s sweeping tariff programme, one of the most ambitious in modern US trade policy, is now facing its greatest test in American courts.

Last week, the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in Washington, DC, ruled in a 7-4 decision that the administration overstepped its authority when it invoked the 1977 International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) to impose broad-based tariffs on a wide range of trading partners.

The judges concluded that the statute, historically used to address emergencies tied to national security and foreign threats, did not give the US president unlimited authority to levy reciprocal duties on imports.

The ruling addressed two separate sets of tariffs. One was the “reciprocal” regime introduced in April this year, covering a wide group of US trading partners.

The second involved duties announced in February against China, Canada, and Mexico, which the administration argued were necessary to combat the inflow of fentanyl into the United States.

The decision did not touch tariffs imposed under other legal authorities, such as the steel and aluminium duties originally set in 2018 under a different statute.

Although the appeals court found the use of IEEPA unlawful in this case, it allowed the contested tariffs to remain in effect until October 14, giving the Trump administration time to appeal to the US Supreme Court.

If the high court upholds the ruling, much of Trump’s current tariff structure could unravel.

How did Bessent defend the IEEPA tariffs?

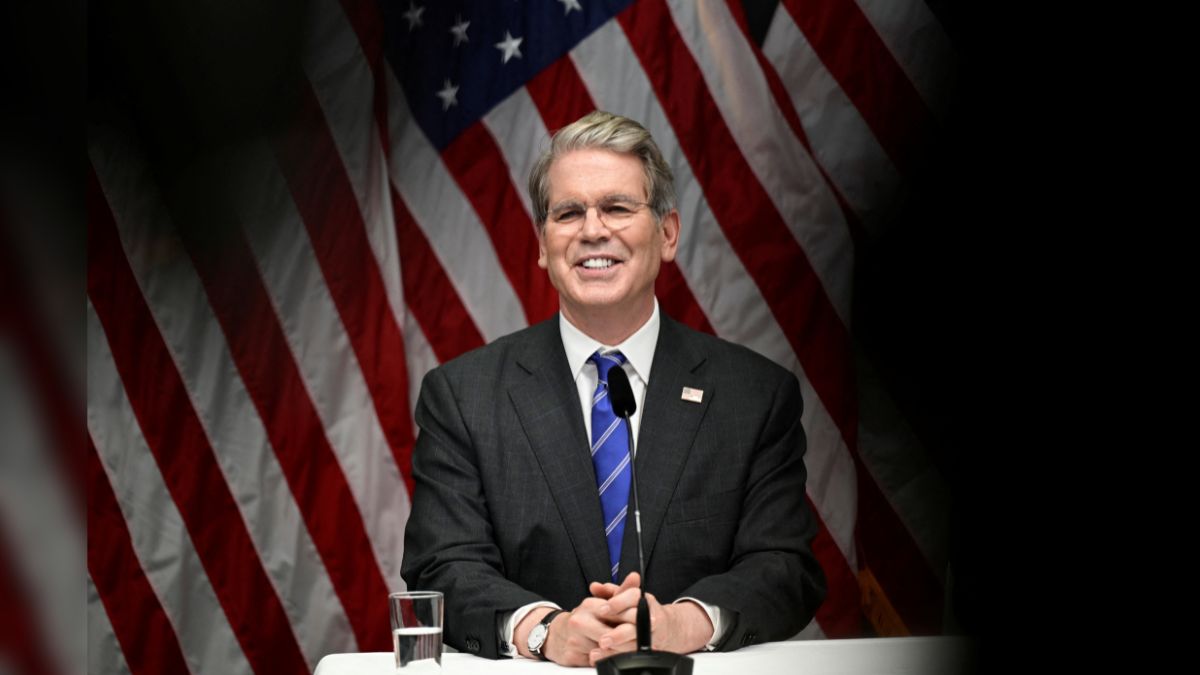

US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has strongly defended the administration’s reliance on IEEPA, describing it as a necessary response to what he called long-neglected economic and security threats.

In an interview with Reuters on Monday, he expressed confidence that the Supreme Court would validate the president’s actions.

“I’m confident the Supreme Court will uphold it – will uphold the president’s authority to use IEEPA. And there are lots of other authorities that can be used – not as efficient, not as powerful,” he said during a visit to a suburban diner near Washington.

Bessent is preparing a legal brief for the US solicitor general that will highlight two central arguments: that decades of persistent trade deficits have put the US economy in a precarious position, and that the fentanyl epidemic represents an extraordinary danger that justifies emergency trade measures.

The Treasury chief pointed to history, arguing that inaction in the face of mounting risks can have devastating consequences.

“We’ve had these trade deficits for years, but they keep getting bigger and bigger,” he explained. “We are approaching a tipping point … so preventing a calamity is an emergency.”

He cited the global financial crisis of 2008-2009, suggesting that earlier interventions in the mortgage market by then-US President George W Bush could have lessened the impact of the housing bubble’s collapse.

By analogy, he said, failing to address trade imbalances and illicit drug flows today could lead to another major crisis.

What is the scope of Trump’s tariffs under IEEPA?

Using IEEPA, Trump has imposed duties on imports from multiple countries, targeting both broad categories of goods and specific products.

His administration has described these measures as necessary to establish “reciprocal” treatment, with US tariffs set at levels equivalent to those charged by trading partners.

The tariffs have also been tied to national security objectives. In February, Washington imposed additional duties on China, Canada, and Mexico, specifically linking them to efforts to curb the flow of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid responsible for tens of thousands of overdose deaths annually in the United States.

Referring to thousands of drug overdoses linked to fentanyl, Bessent told Reuters, “If this is not a national emergency, what is?”

“When can you use IEEPA if not for fentanyl?”

While critics questioned the connection between tariffs and drug enforcement, the administration argued that economic leverage could be used to pressure foreign governments into taking stronger action.

These moves build on earlier trade policies from Trump’s first term. Between 2018 and 2020, the administration used various statutes to introduce duties on steel, aluminium, solar panels, washing machines, and hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of Chinese imports.

Those measures reshaped US trade relations and remain partly in force, even after adjustments during US President Joe Biden’s administration.

What is Trump’s Plan B for tariffs?

Bessent made clear that the White House is not relying solely on IEEPA to defend its tariff programme. He pointed out that “other authorities” exist within US trade law that could be used to maintain tariffs if the Supreme Court strikes down the current approach.

One of the provisions under consideration is Section 338 of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, which allows the president to impose tariffs of up to 50 per cent for five months on imports from countries that discriminate against US commerce.

“There are lots of other authorities that can be used – not as efficient, not as powerful,” he noted.

The Smoot-Hawley law, notorious for escalating global trade tensions during the Great Depression, has rarely been cited in modern policymaking. The US Senate’s official history describes it as “among the most catastrophic acts in congressional history.”

While Section 338 has never been used to impose duties, its existence provides a potential legal pathway for the administration. Bessent indicated that the possibility of invoking it was part of the administration’s contingency planning.

Beyond Smoot-Hawley, the administration has a menu of statutes that could be deployed, each with different processes and limitations:

Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 authorises tariffs on imports deemed to threaten national security. It requires a US Commerce Department investigation, with conclusions delivered to the president within 270 days. Trump has already used this statute to impose tariffs on steel and aluminium, automobiles, and copper. Additional investigations are underway into timber, semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, trucks, critical minerals, aircraft, unmanned aerial systems, polysilicon, and wind turbines.

Section 201 of the Trade Act of 1974 allows tariffs if increased imports cause or threaten serious injury to US manufacturers. Investigations must be conducted by the US International Trade Commission, which is required to hold public hearings and submit findings within 180 days. Tariffs under Section 201 are capped at 50 per cent above existing rates and can last up to eight years with gradual reductions after the first year. Trump used this authority in 2018 to impose duties on solar panels and washing machines.

Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 gives the president, through the US Trade Representative, the ability to impose tariffs in response to discriminatory practices or violations of trade agreements. While investigations and consultations with foreign governments are mandatory, the statute does not cap tariff levels. Trump’s first administration relied heavily on Section 301 during its trade conflict with China, targeting hundreds of billions of dollars in imports. In July this year, a new investigation was launched into Brazil, focusing on trade practices, intellectual property, deforestation, and ethanol access, with tariffs introduced on August 6 under IEEPA.

Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974 permits temporary tariffs of up to 15 per cent for 150 days to address severe balance-of-payments deficits or protect the US dollar. Congress must approve extensions beyond this initial period. Though never used, courts have noted that this statute is more directly relevant to trade deficits than IEEPA.

Together, these authorities form what might be called a “Plan B” for the Trump administration.

How have markets & global players responded?

The appeals court’s ruling, announced just before the Labour Day holiday, left financial markets without a chance to immediately react. On Monday evening, futures tied to US stock indexes were little changed, suggesting that investors were adopting a wait-and-see stance.

Market participants appear to have grown accustomed to the volatility surrounding Trump’s tariff policies, with the expectation that legal battles and policy shifts are ongoing features rather than short-term shocks.

Still, the possibility of an eventual Supreme Court decision against the administration raises significant questions for businesses that have already adjusted supply chains and pricing strategies in response to the current duties.

Critics of Trump’s tariff approach argue that it risks isolating the United States and encouraging rival powers to align against it.

China recently hosted leaders from 20 non-Western countries at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit, drawing attention to growing coordination among states wary of US trade restrictions.

Bessent, however, dismissed the significance of such gatherings. “It happens every year for the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation,” he said.

“It’s more of the same. And look, these are bad actors … India is fuelling the Russian war machine, China is fuelling the Russian war machine … I think at a point we and the allies are going to step up.”

He also suggested that Washington was gaining traction with European partners in efforts to penalise India for its purchases of Russian oil.

A 25 per cent tariff was imposed on those imports, and discussions continue with allies about broader measures.

By contrast, he did not comment on whether similar pressure would be applied to China.

According to Bessent, China faces inherent limitations in diversifying away from Western markets. “They don’t have a high enough per capita income in these other countries,” he noted, arguing that alternatives to the US and European markets are insufficient to absorb China’s export capacity.

With inputs from agencies

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)