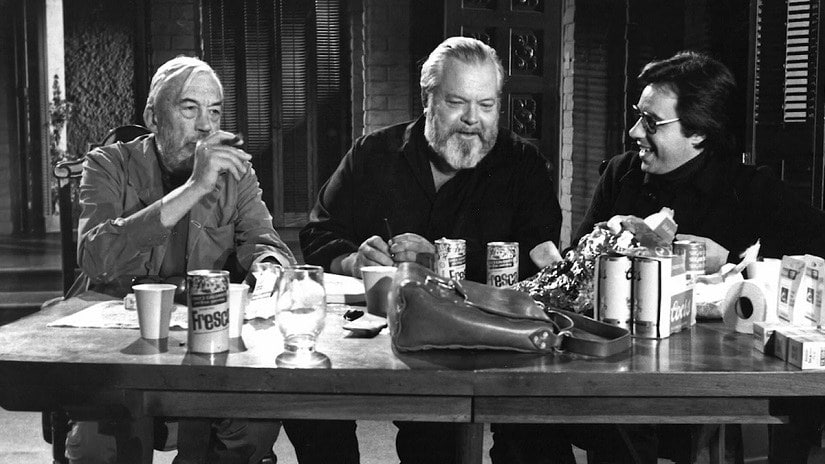

Hollywood loved calling it the “Greatest Movie that was Never Made.” That jinx about Orson Welles’ last feature film, The Other Side Of The Wind, was broken this month when it finally released on Netflix, 42 years after its shooting was completed. Few films sum up the word enigma as Welles’ swan song does, in terms of its back story as well as cinematic content. The back story first: Hollywood titan Welles shot the film between 1970 and ’76 and then futilely struggled to complete post-production till his death in 1985. Thirty-three years after his demise, veteran producer Frank Marshall and Oscar-winning editor Bob Murawski took the initiative to craft out a 122-minute feature for commercial release, carefully sifted out of the massive footage Welles had shot but could not ultimately edit into a feature film. [caption id=“attachment_5537051” align=“alignnone” width=“825”] (From L-r) John Huston, Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich on the set of The Other Side Of The Wind. Netflix[/caption] “Wells died in 1985, leaving behind nearly 100 hours of footage, a workprint consisting of assemblies and a few edited scenes, annotated scripts, memos, thoughts and directives. The film is an attempt to honour and complete his vision,” runs an announcement at the start of the film. Obvious question: Would Welles have edited the film the same way Marshall and Murawski have done? Can anyone say for sure the (definitely brilliant) end product that the duo — masters of their respective arts — has catered is exactly what Welles had in mind? We will never know, and for that reason a conventional review of The Other Side Of The Wind as an Orson Welles film would perhaps seem unfair. If post production, particularly editing, is a significant aspect of filmmaking, Welles never wholly participated in that process. Movie buffs are thrilled with the layered feast in store. The film, shot in cinema-vérité style to underline its quasi-autobiographical intent, is centered on Jake Hannaford (played by the late John Huston), a Hollywood lion in his winter. The character is obviously modeled on Welles. Hannaford is struggling to release his last movie, titled The Other Side Of The Wind, and which is to be screened at a big-ticket party hosted in Hannaford’s honour by a close friend. Welles uses a film-within-film approach, with parallel narratives setting apart the real and the reel. While the brooding back story of Hannaford and his party animal cohorts underlines his physical and mental state, the film within the film becomes a mirror reflecting Hannaford’s (and, by proxy, Welles’) creative state of mind in his last years. The film within the film, in fact, renders edge to the overall narrative. Wanton in spirit and soaked in moody psychedelia, it is executed with new-wave relish and looks surprisingly uninhibited for a Hollywood feature of the seventies, in its graphic depiction of sex, nudity and drug use. Welles, returning to the movies after a decade in exile, is clearly angry at a lot of what was going on in Hollywood at that point — a fact evident from Hannaford’s character sketch. He reserves no apologies in introducing Hannaford as the “Ernest Hemingway of cinema” early on. The self-congratulatory note continues in a scene where Hannaford is seen discussing the art of filmmaking: “It’s relatively easy to make a good movie… not a great one, that’s something else.” His bitterness for a lot of what was succeeding in Hollywood of the seventies is obvious in the ridicule-tinted sadness communicated through words of a lesser character: “It’s a whole new business. The actors, the stars even… I don’t know their names.” A couple of harmless merry winks at Italian arthouse powerhouses Bernardo Bertolucci and Michelangelo Antonioni don’t go unnoticed, but Welles is far more ruthless towards those he abhors. Film critic Pauline Kael, for instance, and author Charles Higham, who wrote a trashy biography of Welles, are scathingly spoofed. But then, there are the self-depreciatory notes too, laden with caustic wit. A character modeled on a business partner who fell out with Welles in his final years, describes Hannaford thus: “Then we must wait, my dear, for him to eat us alive, unless you are a critic. He does rather tend to push them to the side of his plate. But others, we who glow a little in his light, the fireflies he does quite often swallow whole. It is a fact that some of us he chews on rather slowly.” The film within film, starring Croatian actress Oja Kodar as its mysterious protagonist, makes for the really intriguing watch, revealing the innermost thoughts of a thespian in his twilight phase. With flourish, Welles’ on-screen mouthpiece Hannaford declares: “Just like me and God. If it wasn’t the difference in sex, how could you tell us apart?” More interesting than Welles equating himself with God is his classifying God as a female entity. It is an interesting departure from what the western world continues to believe. The Other Side Of The Wind was one three film projects Welles left incomplete at time of death (the others being Don Quixote and The Merchant Of Venice). Of these, a reconstructed version of The Merchant Of Venice was screened at the Venice fest in 2015. Not much footage remains of Don Quixote, but an attempt to screen a print constructed out of available footage was done in 1992, to negative reactions. Perhaps these incomplete films, as well as 20-odd screenplays that lie pending since his death, reveal a maestro’s crumbling conviction for his art in his last days.

(From L-r) John Huston, Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich on the set of The Other Side Of The Wind. Netflix[/caption] “Wells died in 1985, leaving behind nearly 100 hours of footage, a workprint consisting of assemblies and a few edited scenes, annotated scripts, memos, thoughts and directives. The film is an attempt to honour and complete his vision,” runs an announcement at the start of the film. Obvious question: Would Welles have edited the film the same way Marshall and Murawski have done? Can anyone say for sure the (definitely brilliant) end product that the duo — masters of their respective arts — has catered is exactly what Welles had in mind? We will never know, and for that reason a conventional review of The Other Side Of The Wind as an Orson Welles film would perhaps seem unfair. If post production, particularly editing, is a significant aspect of filmmaking, Welles never wholly participated in that process. Movie buffs are thrilled with the layered feast in store. The film, shot in cinema-vérité style to underline its quasi-autobiographical intent, is centered on Jake Hannaford (played by the late John Huston), a Hollywood lion in his winter. The character is obviously modeled on Welles. Hannaford is struggling to release his last movie, titled The Other Side Of The Wind, and which is to be screened at a big-ticket party hosted in Hannaford’s honour by a close friend. Welles uses a film-within-film approach, with parallel narratives setting apart the real and the reel. While the brooding back story of Hannaford and his party animal cohorts underlines his physical and mental state, the film within the film becomes a mirror reflecting Hannaford’s (and, by proxy, Welles’) creative state of mind in his last years. The film within the film, in fact, renders edge to the overall narrative. Wanton in spirit and soaked in moody psychedelia, it is executed with new-wave relish and looks surprisingly uninhibited for a Hollywood feature of the seventies, in its graphic depiction of sex, nudity and drug use. Welles, returning to the movies after a decade in exile, is clearly angry at a lot of what was going on in Hollywood at that point — a fact evident from Hannaford’s character sketch. He reserves no apologies in introducing Hannaford as the “Ernest Hemingway of cinema” early on. The self-congratulatory note continues in a scene where Hannaford is seen discussing the art of filmmaking: “It’s relatively easy to make a good movie… not a great one, that’s something else.” His bitterness for a lot of what was succeeding in Hollywood of the seventies is obvious in the ridicule-tinted sadness communicated through words of a lesser character: “It’s a whole new business. The actors, the stars even… I don’t know their names.” A couple of harmless merry winks at Italian arthouse powerhouses Bernardo Bertolucci and Michelangelo Antonioni don’t go unnoticed, but Welles is far more ruthless towards those he abhors. Film critic Pauline Kael, for instance, and author Charles Higham, who wrote a trashy biography of Welles, are scathingly spoofed. But then, there are the self-depreciatory notes too, laden with caustic wit. A character modeled on a business partner who fell out with Welles in his final years, describes Hannaford thus: “Then we must wait, my dear, for him to eat us alive, unless you are a critic. He does rather tend to push them to the side of his plate. But others, we who glow a little in his light, the fireflies he does quite often swallow whole. It is a fact that some of us he chews on rather slowly.” The film within film, starring Croatian actress Oja Kodar as its mysterious protagonist, makes for the really intriguing watch, revealing the innermost thoughts of a thespian in his twilight phase. With flourish, Welles’ on-screen mouthpiece Hannaford declares: “Just like me and God. If it wasn’t the difference in sex, how could you tell us apart?” More interesting than Welles equating himself with God is his classifying God as a female entity. It is an interesting departure from what the western world continues to believe. The Other Side Of The Wind was one three film projects Welles left incomplete at time of death (the others being Don Quixote and The Merchant Of Venice). Of these, a reconstructed version of The Merchant Of Venice was screened at the Venice fest in 2015. Not much footage remains of Don Quixote, but an attempt to screen a print constructed out of available footage was done in 1992, to negative reactions. Perhaps these incomplete films, as well as 20-odd screenplays that lie pending since his death, reveal a maestro’s crumbling conviction for his art in his last days.

The Other Side Of The Wind reveals Orson Welles' crumbling conviction in cinema in his twilight years

Vinayak Chakravorty

• November 14, 2018, 13:51:15 IST

In The Other Side Of The Wind, Orson Welles uses a film-within-film approach, with parallel narratives setting apart the real and the reel.

Advertisement

)

End of Article