At 350 crores, Saaho is supposedly the most expensive Indian film ever made. But it has received extremely negative reviews from critics. Its director Sujeeth made his first film Run Raja Run in 2014 at the age of 23. Wikipedia also adds the following about him: “He directed about 38 short films before entering Telugu cinema. Prior to films, Sujeeth started to study to be a chartered accountant, but eventually quit to pursue his passion for filmmaking. He is the best friend of Anirudh Tirunamalli.” Big budget films once rode on prestigious directors, but today, trust seems to be placed on marketing strategies rather than the product itself. Instead of reviewing Saaho, therefore, it may be more interesting to speculate on the condition of Indian cinema, if the industry is willing to risk Rs 350 crores on a greenhorn director.

At the very least, one might say that the director is no longer an important consideration in Indian popular film.

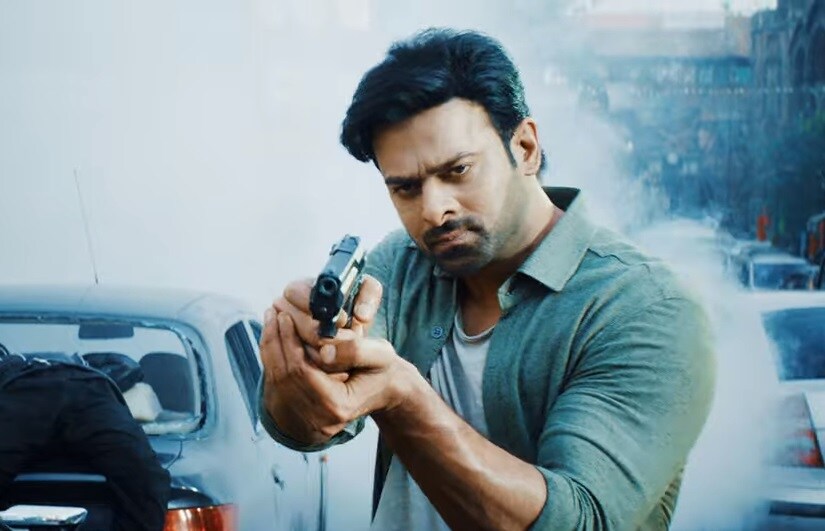

But it is not only Saaho which has been entrusted to a novice. The Kannada film KGF, also the most expensive film from the Kannada industry and its biggest earner, was also entrusted to a director with only one film to his credit. Both films have been described as visually impressive, but what they mostly offer are aerial views, digitally created spaces and close-ups of guns fired. The frames appear monochrome, the stars muscular people with small screen presences. One cannot be sure of their physiques, since they also look digitally enhanced. Yash, the hero of KGF, was not even visible in the film since he was hiding behind a beard. This fact about KGF leads us to wonder if even stars are an important consideration, except to their respective fan followings. [caption id=“attachment_6805491” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Prabhas in a still from the Saaho teaser. YouTube screenshot[/caption] Both KGF and Saaho are South Indian films targeting the Hindi film market, which suggests a larger audience for each film than a decade ago, when regional cinema and Bollywood were separate. The kind of cinema one watches, one might conclude, is not a marker of one’s cultural identity. Finally, if the story was what audiences once responded to, few engaging stories are being told. If one were to describe what Saaho is about, one could say that it was about a foreign criminal syndicate led by gangsters with Indian names, operating from a haven called Waaji that might be Wakanda from Black Panther. The syndicate, reminiscent of the Mission Impossible franchise, is not anti-Indian as Mogambo was in Mr India (1987) was. Rather, it is a patriotic picture of what Indians can be in the world, even its criminals never less than arch-criminals. The syndicate is called the ‘Roy Group’, headed by Narantak Roy (Jackie Shroff), and at the commencement of the film, this man is killed in a car accident in Mumbai. There is a struggle for power between his son and another criminal from the syndicate, Devraj (Chunky Pandey). The syndicate is well managed, since it has a legal advisor called Kalki (Mandira Bedi), who has a PhD from Oxford. The criminals are after something called ‘the black box’ that allows them access to a treasure worth two lakh crores – about the same magnitude as the government’s outlay on one of its schemes – stolen through mysterious robberies in Mumbai. The people hunting them are the police in Mumbai, its star Ashok Chakravarthy (Prabhas), his boss played by Prakash Belvadi, and other officers including Amritha Nair (Shraddha Kapoor), whose presence induces Ashok Chakravarthy to take up the assignment, though he is not inclined to. There are twists and turns and some supposed police officers are actually criminals affiliated to the syndicate. It is all so confusing that one needs to consult Saaho’s Wikipedia entry even while watching the film. Saaho is an action film, but there were, we supposed, requirements for laying out the action sequences. In the first place, there need be good guys and bad guys and we should be able to tell them clearly apart. We also identified with one lot against the others, and our excitement depended on this identification, our sense of elation or dismay depending on what was happening to whom. Saaho is a film in which this need for identification has been eliminated altogether, since those we supposed were good turned out to be criminals. Also, the fact that the good-turned-bad are with the police causes another difficulty. The police represent the State and they create a foundational basis for our emotional responses. Police officers identified with the protagonists cannot be found to be members of criminal gangs. Such turns make us lose our balance with regard to whom to identify with or what cause to back. The only emotion that seems to be stable in Saaho is the attractions of the sum of two lakh crores, and the action sequences all lead up to the protagonist and his girlfriend eventually pocketing it. One wonders if that is what keeps audiences in the cinema hall – dreaming of so much money. [caption id=“attachment_7285621” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  In Saaho, the frames appear monochrome, the stars muscular people with small screen presences[/caption] Saaho is a strong contender for the title of the Worst Indian Film Ever Made, but what needs sociological investigation is how it got made at all. Critics, while complaining about its confusion, have commended the action sequences, as though seeing nondescript people killing faceless others in various ways is itself a draw. Following popular film narrative was never an intellectual feat by any stretch of the imagination, but Saaho does not even demand that. Some critics have actually appreciated the fact that people laugh at dramatic moments, concluding that Saaho was hence highly enjoyable as entertainment. Sample one sequence in which Prabhas (I’m not sure whether as policeman or arch-criminal) jumps off a cliff chasing after a backpack containing a parachute, grabs it, fastens it onto his shoulders, pulls its chord and descends safely downwards to the ground. With the generous guess that the cliff was 2000 feet high, school physics tells us it would take only 11 secs for Prabhas to hit the ground. But this kind of thing is routinely shown in popular films as ‘exciting action entertainment’. When we contemplate the intellectual capacity in the general public, we consider things like modes of expression and the quality of imparted education, but we do not see popular entertainment as indicative? Whatever popular film as entertainment was available in the last century made greater demands on us as audiences, since we were asked to follow stories, regard stars in terms of the characters they were playing and there was no confusing the stars from one another. Dilip Kumar was not NT Rama Rao, but stars like Prabhas are disposable bodies. Even in terms of visual appeal, films shot on location or on sets had more items of interest per frame than the digitally created images proliferating in Saaho, the product of a stale imagination. In Saaho, one is not even sure that munching popcorn in the interval does not make fewer intellectual demands on us than watching the film. The decline of film entertainment in India could be a useful way to chart the country’s decline as a cultural space. MK Raghavendra is a film scholar and author of seven books including The Oxford India Short Introduction to Bollywood (2016)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)