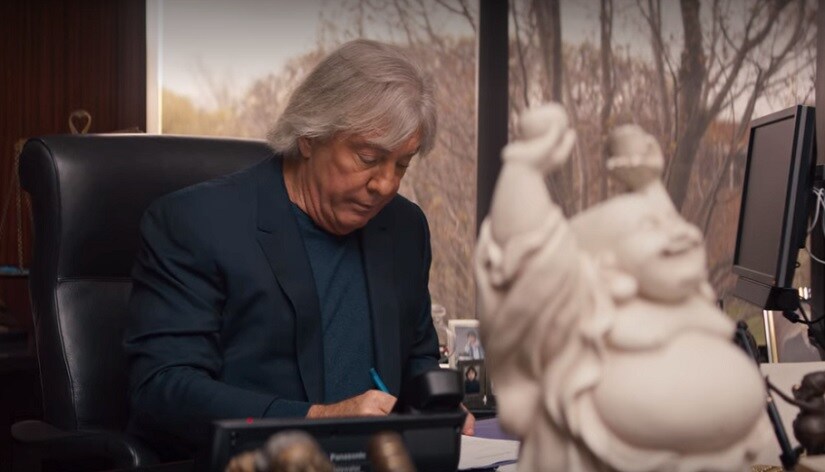

Having worked in the entertainment industry for over 36 years, George Clooney knows a thing or two about the media. In the last film he acted in — Jodie Foster’s Money Monster (2016) — Clooney played a TV personality who advises the audience on financial investments, but is abducted by a disgruntled viewer who is bankrupted after following his tips. Sometimes, a passing occurrence on TV can lead to unintended real life consequences. This is just what Clooney’s newest co-production — the Netflix docuseries Trial By Media — reiterates. Trial By Media highlights six instances (over as many episodes) where the media played a crucial role in shaping the narrative, and possibly influencing the verdict of a court case. (India of course is no stranger to the phenomenon, having seen this same effect in cases such as KM Nanavati vs The State of Maharashtra, and the Jessica Lal, Arushi Talwar murder cases.) The first episode/documentary in Trial by Media — ‘Talk Show Murder’, about the 1995 murder of Scott Amedure by his friend Jonathan Schmitz — traces these connections especially well. [caption id=“attachment_8364531” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Scott Amedeur and Jonathan Schmitz in a still from Trial By Media | Netflix[/caption] Amedure and Schmitz were invited to participate on a reality/talk programme known as The Jenny Jones Show — a Warner Bros production that typified the genre of “ambush” or “trash” TV, where regular citizens were invited to make “shocking” personal confessions on camera. ‘Talk Show Murder’ begins with a montage of these confessions, where participants on The Jenny Jones Show reveal their sexual orientations or the details of an affair. The manner in which the recipients of these admissions reacted — awkward smiles, stumped silence — is controlled, courtesy the cameras trained on them and the presence of the studio audience, hooting or chiming in with applause as indicated by the lighted sign looming overhead. The set-up is not dissimilar to contemporary reality TV shows. During their appearance on The Jenny Jones Show, Amedure confessed to having nursed a secret crush on Schmitz; four days later, Schmitz shot Amedure dead at the latter’s home, then turned himself in to the police. In court, Schmitz’s history of mental health issues and The Jenny Jones Show were presented as the causes for his killing Amedure. Schmitz was convicted of second-degree murder, while Warner Bros was later sued by the Amedure’s family on charges of negligence. In ‘Talk Show Murder’, Robert Lichter, director — Centre for Media and Public Affairs, comments that host Jenny Jones “started [by] wanting to be another Oprah Winfrey” but realised which way success (or infamy) lay, and became “a Jerry Springer” over time instead. Lichter notes that it was not only Jenny but also a host of other TV personalities who propelled the trend of ambush television. “In the 1990s, Hollywood realised the best opera is real life,” says Lichter, adding that everything from marital troubles to one night stands were being minted for money. “Nobody realised that these were real people, with real problems, and real secrets.” [caption id=“attachment_8364541” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  A still from Trial By Media[/caption] Amid the backlash over Amedure’s murder, Jenny Jones claimed that what happened was the result of an individual action, and had little to do with her show. Many of her peers justified the genre of “trash TV” with statements like, “You say it’s trash? That’s rather elitist. This is America!” and “[saying] trash TV is responsible for something is like saying the reason I’m getting fat is because of that refrigerator out there”. This defense is one that routinely comes up even today when debating the ethics of providing sensationalist, manipulative content. “But people love watching it. If they stop watching it, we’ll stop making such content.” This “demand-supply” rationale is also touted for 24/7 TV news channels that have eschewed information in favour of “entertainment”. The sort of crass sensationalising of news that has marked a section of Indian news media’s coverage of events such as the actress Sridevi’s death is a throwback to how parts of the American press reported on Schmitz’s murder trial, promising “gavel-by-gavel coverage” of the court proceedings. In ‘Talk Show Murer’, Lori Braiser, a reporter with the Detroit Free Press, remembers her unease with the media coverage of the case: “We were exploiting the people who were exploiting others,” she says. “I still battle with the thought of how we covered that entire case.” Among the many dubious aspects of the case was Court TV’s detailed coverage of the Amedure family’s trial against Warner Bros. Court TV was owned by Warner Bros. Scott Amedure’s older brother, understandably incensed, says in ‘Talk Show Murder’: “First, they exploit my brother for their ratings. Then they exploit him further by covering a case where we’ve sued their company for causing my brother’s murder.” [caption id=“attachment_8364551” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Jenny Jones in a still from Trial By Media | Netflix[/caption] For their fight against a corporate giant, the Amedures brought in celebrity lawyer Geoffery Fieger. Dismissed by his rivals as a “press animal” and “publicity hound”, Fieger specialised in high-profile cases that may not have been easy to win, but certainly added to the story he wished to tell of himself. A Drama major in college, Fieger equated a lawyer’s job to a painter’s: “I like to tell a story. I like to paint a picture. If you want to convince the jury, you need to be able to tell a story to a human,” he says in ‘Talk Show Murder’, encapsulating the philosophy of his courtroom appearances. Fieger led the Amedures to victory against Warner Bros in what the press described as a David-Goliath match, even though a higher court overturned the verdict three years later. The Amedure-Schmitz case illumined how drama and sensationalism — two integral constituents of entertainment — pervade various spheres of our society, be it the media, law or personal relationships. The drama is both cause and effect, and so insidious that even the makers of Trial by Media/‘Talk Show Murder’ do not realise the many times they exploit the case and those associated with it. Like The Jenny Jones Show, Trial By Media also cashes in on the plight of real people and their emotions, inadvertently triggering past trauma that perhaps these individuals have since moved on from. The story becomes the story, and the practice of emotional manipulation for the sake of entertainment operates cyclically. [caption id=“attachment_8364591” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Geoffery Fieger in a still from Trial By Media[/caption] While Scott Amedure’s brother consented to speak on camera, Schmitz and Jones refused. We see Jones blaming the press for manipulating the narrative against her show. And the last we see of Schmitz is him evading the waiting camera as he walks out of prison on completing his sentence. An associate rebukes the reporter chasing Schmitz: “Mister, you need to get a life.” The Jenny Jones Show claimed to have sought verbal consent from Amedure and Schmitz for their participation in the programme (and all that it entailed); there doesn’t seem to be any documentary proof to support that assertion. But even if the evidence indicated otherwise, does the mere seeking of permission then make it okay to exploit another’s emotions? Trial By Media/‘Talk Show Murder’ at least seems to be aware of the collateral damage involved in bringing the Amedure-Schmitz case back into the spotlight’s glare. Its final scene shows Amedure’s brother being asked by the documentary team: “What do you think he would be doing today?” “Maybe he’d be with you guys. He loved doing all this. He wanted to be on TV. It was his thing,” Scott’s brother replies. Clearly, the lure of entertainment might have proved too hard to resist.

The very first episode of the George Clooney-produced docuseries reexamines the 1995 murder of Scott Amedure by Jonathan Schmitz, and the reality TV circus that both fed and followed it.

Advertisement

End of Article

Written by Devansh Sharma

Twitter handle - @inkedinwhite see more

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)