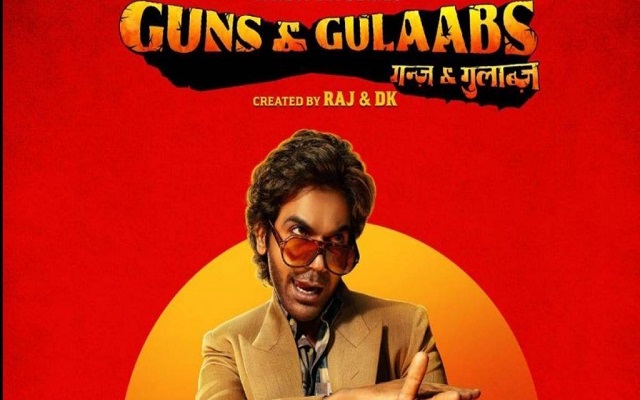

In a scene from Raj and DK’s Netflix show Guns and Gulaabs, Tipu, played by the show-stealing Rajkummar Rao, exclaims “Main Tipu Tiger nahi Tipu Motor hi theek hun.” Tipu is of course referencing his late father’s violent legacy. A legacy that he is expected to carry forward. Except, he is cut from a different fabric. This bit of dialogue probably applies to Rao’s work as well. For long, justifiably lauded as the finest of his generation, Rao’s career had, briefly, begun to circle the lid of self-absorbed projects that eventually sunk down the pipeline of visible self-regard. At one point, it even felt like the actor had keeled over to the pressure of his own hype, spilling himself into poor scripts and tacky, grave, what they call in Hollywood ‘Oscar-bait’ roles. As Tipu, Rao marks a stellar resurgence, as maybe a comedic master whose desire to be taken seriously, adds to the farce his characters eventually come to represent. For a few months after the release of Hansal Mehta’s Omerta(2017), Rao seemed to speak with an air of superficiality. Every interview, roundtable or bite he sat in for, he sounded the kind of self-serious artist who obsessed about the perception of his methods far more than the work itself. For some time, his career even looked to being going astray. Half-assed roles like Made in China, Roohi, Hum do Humare Do, with the undeniably awkward turn as an English-speaking NRI from The White Tiger sandwiched in between, for a couple of years at least, nothing seemed to click into gear. And this is an actor who started out with promise so exotic and trailblazing, it practically ushered in an era of filmmaking that he considered synonymous with. Maybe the key to rediscovering that streak was to let go of the burden of damp perfection, in favour of crisp vivacity. Through the years of this rough patch – by his own standards - there were signs of what might rejuvenate, or maybe even reconfigure a gifted actor in ways he himself maybe could not visualise. In Anurag Basu’s messy, eccentric comedy caper Ludo, Rao plays Kabir, a sweet, gullible man whose relentless pursuit of a woman, opens him up to both ridicule and tragedy. It isn’t Kabir’s stupidity that humanises him, but his lovable doggedness, the suicidal conviction with which he pursues that which is destined to destroy him. In Badhaai Do, perhaps the film to signal Rao ’s return to form, he plays Shardul, a gay man hiding behind the steely but fragile exterior of a police officer. It’s a landmark role, made iconic by Rao’s lightness of touch, the fact that for a change, it was the featherweight actor driving the character, as opposed to the pomp that a reputation like his could so easily turn to. Rao’s comedic abilities had been established by the hit Stree, but with Badhaai Do, he helmed an interiority, capable of exhibiting the humanity wrapped inside the superficial skin of a joke. In Monica Oh My Darling, Rao plays Jayant, a robotics expert, who despite the sheen of scientific knowledge, sports the arms of social incompetence. He panics easily, can’t think straight under pressure, and doesn’t quite possess the authority expected of men, faced with a draining turn of events. Fragility, isn’t quite the anchor of new-age masculinity yet, but Rao has extracted humour from exhibiting vulnerability in its physical form. In a hilariously dark scene he runs out of breath trying to fist-fight Huma Qureshi. It’s a widely discussed scene that underlines why the actor’s diffidence, works in his favour. That he has recently played love-struck men, hopelessly pursuing women, also contradicts the jingoistic 90s. His is a softer, more dogged pursuit but with ample room for kindness and empathy. It’s a world, where the idealism of love is as vulnerable as the idea of machoism. And Rao’s ability to build comedy around these dated ideas, elevate them to more than mere slapstick. Guns and Gulaabs is sluggish in its middle, somewhat handicapped by its own varied canvas. The characters appear to have ticks, but rarely do they exhibit something akin to an organic inner life. Everyone except Tipu, whose clueless extremes, Rao perfectly assembles within a fidgety, nervous body. It’s comic, in a tragic sort of way. Tipu has inherited violence but refuses to claim it until the last moment. He has inherited innocence, but love, at least its carnal pursuit, mandates a bit of wildness, maybe even menace. It’s probably why the woman he is chasing, admires him for the man he can become, as opposed to the man he thinks he is. He’s here and nowhere at the same time, a character so loony, reckless and unsure, he could so easily be lost. Except with Rao, he isn’t.

As Paana Tipu in Netflix’s Guns and Gulaabs, Rao embellishes a rich, at times tediously self-serious career, with the crown of undeniable comedy gold.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)