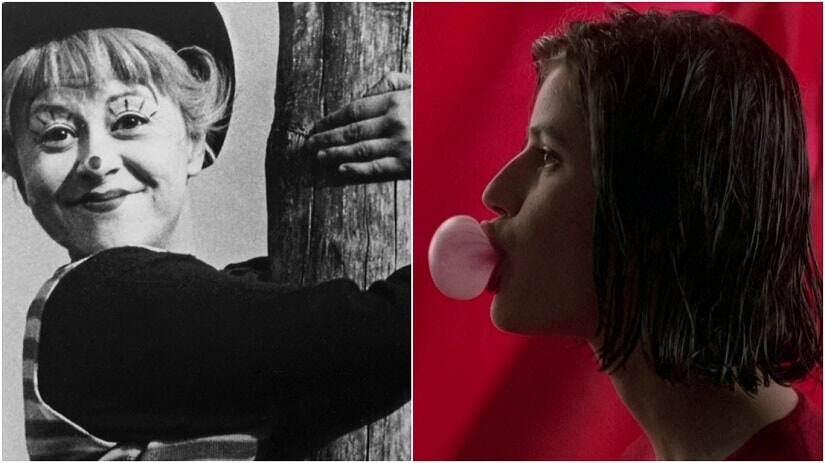

My editor asked me to follow up last week’s column with a list of foreign-film favourites, and there are two ways to go about this. One is to follow the establishment-approved route, and talk about Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai, Jiří Menzel’s Closely Watched Trains, Fritz Lang’s M, Jean Renoir’s Rules of the Game, one of the many Buñuels, Alain Resnais’s Hiroshima Mon Amour, so on and so forth. These are all… worthy films. They are all… must-sees. They are all… landmarks in the history of cinema. They are all… not the films that instantly spring to mind when I think of “favourites”. In the sense that these are films that I admire, that I have seen several times, that have taught me a lot – and yet, they’re not the films I’d reach for unless I’m in the mood. You know the mood I’m talking about. It’s the mood that says “I think I’ll have some steamed broccoli for dinner”. Hence, the other route, which is a list of films I don’t just admire but also love. These are films I’d sit down to watch anytime. They’re personal. For various reasons, they speak to me. And if I’ve not mentioned two absolute favourites (Pedro Almodóvar’s Talk to Her, Alfonso Cuarón’s Y Tu Mamá También), it’s because I have spoken about them many times and I wanted to make space for other films. [caption id=“attachment_5870121” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Stills from Fellini’s La Strada (L) and Kieslowski’s Three Colours: Red. Wikipedia commons[/caption] Making such a list is at once useful and meaningless. The latter, because it’s my list and the films may not speak to you the same way at all. But useful, because it tells me that French is my go-to language for foreign films, or that I don’t love Iranian cinema as much as I admire the films (not a single one popped up instantly). Also, I was amused that the same year kept popping up, with two films from 1965, two from 1971, two from 1982. Is my subconscious telling me something? Anyway, here’s the list. 1. La Strada (Federico Fellini, 1954): My favourite Fellinis are his more out there existential extravaganzas (say, 8½), but this is my first memory of watching a foreign film on the big screen. I was a teenager. This was at the Madras Film Society. I had trouble keeping my eyes open after a point, at the time, but now, this drama about a waif sold to a travelling showman is my definition of a personal piece. 2. The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (Jacques Demy, 1964): Oh, how I love this musical. It took me a while, though. The whole film is sung (like an opera), and it took multiple watches to get a handle on the tunes (many of which get repeated, and are crucial motifs for the characters). But once you know the score, I dare you not to be moved. Every time I watch the last scene, it breaks my heart. 3. Pierrot Le Fou (Jean-Luc Godard, 1965): Godard is always interesting on some level, though I admire most of his films than actually love them. But the Raoul Coutard-shot colour films from this period (including Contempt) are gorgeous, as much a feast for the eye as brain fodder, and surprisingly (for this filmmaker) emotional. Jean-Paul Belmondo and Anna Karina as – in Godard’s words – the “last romantic couple”. Enough said. 4. Red Beard (Akira Kurosawa, 1965): Toshirô Mifune, who gets one of the greatest “hero-introduction shots” of all time, plays a gruff doctor in 19th-century Japan. The film, filled with astonishing compositions (even for this director), is like King Lear – it plays better as you grow older, when you have seen more of the world. “Even bad food tastes good if you chew it well. Same with our work here, if you try hard.” When younger, this line appears to be just poster-worthy philosophy. When older, you realise it’s life. 5. Playtime (Jacques Tati, 1967): The first few times I tried watching this hilariously deadpan comedy (which is more like a complex piece of choreography), I gave up after thirty-odd minutes. (I think I expected more straight-out laughs.) But something clicked eventually, and I saw why the film theorist Noël Burch called it, “the first [film] in the history of cinema that not only must be seen several times, but also must be viewed from several different distances from the screen”. That may be a bit of oversell, but Playtime is a gift that keeps on giving. 6. Solaris (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1971): One trick to get into “difficult” films (or filmmakers) is to pick one whose subject fascinates you. With Robert Bresson, for me, it was Lancelot du Lac (I am a huge fan of the Arthurian legends), and the sci-fi/romance aspect of Solaris makes it a relatively easy entry point for Tarkovsky. And with multiple viewings, when you finally sync into the film’s rhythms without the crutch of “genre’, it’s as much a space/time experience for you as the protagonist. 7. Two English Girls (François Truffaut, 1971): In the Godard-versus-Truffaut war, I’ve always been more of a fan of the latter. (The camp you pick says something about you. It’s as much a Rorschach test as “Beatles or Stones?” or “Tintin or Asterix?”.) Watch this Jean-Pierre Léaud drama as a double bill with Jules et Jim, and you can spend many a happy hour debating which bohemian love triangle is more devastating. 8. Fanny and Alexander (Ingmar Bergman, 1982): I’m trying to remember the first Bergman I saw, and it’s not coming to mind. Oh well! But I do know it’s one of the grim ones, like Winter Light. The magical Fanny and Alexander, though, is as sunny as that other film is dark. One of my favourite films from one of my favourite filmmakers, and about one of my favourite subjects: about the “can’t live with them, can’t live without them” nature of large families. 9. Fitzcarraldo (Werner Herzog, 1982): This isn’t just the story of a magnificent madman who wants to build an opera house in a remote Amazonian port. It’s about everyone who sits down in front of a blank screen and sets out to write. Or paint. Or compose. Sounds pompous? But then, several friends of mine in “regular” jobs have said they don’t seem to connect to the film beyond the fact that it’s just… a bloody great film. You tell me. 10. Three Colours: Red (Krzysztof Kieslowski, 1994): I’d always been a fan of the Trilogy (Red is my favourite), but what really changed the way I viewed the films were the DVD commentary tracks by film scholar Annette Insdorf. This is not to say you have to interpret these interlocking puzzle-films the very same way, but it was an eye-opener for me on how to read cinema. And few filmmakers’ films allow themselves to be “read” more.

Here’s Baradwaj Rangan’s list of his favourite foreign films.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)