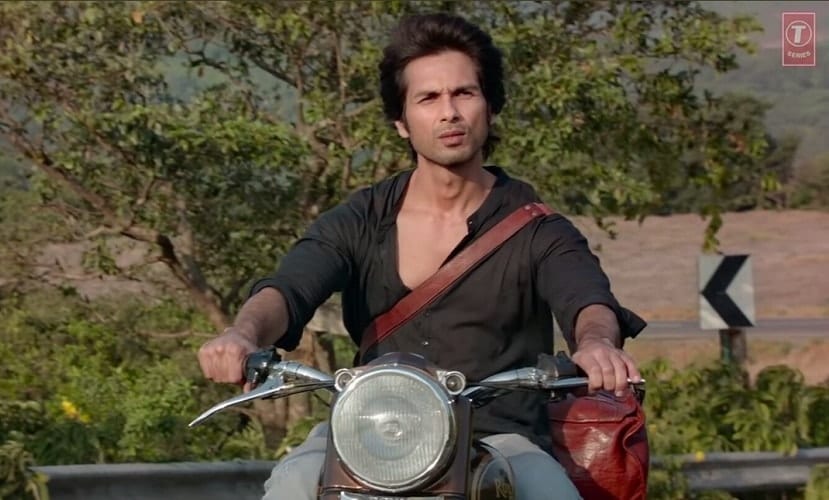

For a film critic, analysing a mainstream film like Kabir Singh should be much more pleasurable than watching it. The film is almost unbearable for its sexism, and if many Hindi film classics — as even some by Raj Kapoor (Sangam, 1964) — are similarly culpable, it nonetheless goes further in this direction. The major reason, I suspect, is that it is the faithful remake of a Telugu popular film and some of the things shown in regional language (especially Telugu) cinema cannot be shown to Hindi film audiences. Hindi cinema is meant for a pan-Indian audience, which means that it must tailor itself not only to be widely understood by non-Hindi speakers but must also try not to cause offence. It has therefore been relatively bland, not placed an emphasis on caste issues and antagonisms, which are in any case local. Kabir Singh is a remake of a film Arjun Reddy made by the same director (Sandeep Reddy Vanga) that belongs to a category wearing its caste affiliations on its sleeve by including it in the title. Many of these films — like Samarasimha Reddy (1999) and Narasimha Naidu (2001) are about caste-based feuds and very brutal. In Samarasimha Reddy the villain is an amputee whose two legs and one arm were severed by the protagonist as revenge for death of his parents, fiancée, sister and brother-in-law at the former’s hands. Some of these exercises — often termed ‘faction films’ locally — supposedly reflect caste antagonisms, both inter-caste rivalry and struggles for supremacy within a single caste. [caption id=“attachment_6734221” align=“alignnone” width=“829”]  Shahid Kapoor in a still from Kabir Singh[/caption] Caste in India has two implications, jati and varna, and while jati is operative locally, varna is an idealised grouping of jatis into four categories – brahmin, kshatriya, vaishya, shudra – that does not find correspondence on the ground, where the correlation between jati and varna is uncertain. The same jati that considers itself ‘kshatriya’ could be considered ‘shudra’ by those outside. Arjun Reddy was caught between two impulses, pride in the jati identity and a desire to downplay it and it therefore named its protagonist ‘Arjun Reddy Deshmukh’, an impractical name for someone in jati-driven society. As if to mirror this jati denial the director is also restricting his own name to ‘Sandeep Vanga’. When regional films invoking jati are remade in Hindi, caste tends to lose significance. ‘Kabir Singh’ could equally have been ‘Kabir Srivastava’, ‘Kabir Pandey’ or ‘Kabir Gupta’, though the kshatriya echoes in ‘Singh’ still suggest the protagonist’s capacity for violence as the appellation ‘Gupta’ might not have. Arjun Reddy may invoke jati but being a youth romance was remade in Hindi as ‘faction films’ could not have. Kabir Singh is a development of Devdas in narrative terms except that, rather than being a self-pitying drunkard, Kabir Singh (Shahid Kapoor) is a brilliant surgeon with ‘anger-management problems’. This sounds like a criticism but the camera photographs the protagonist from below to make him tower above us when he is out brawling or accosting women students in his medical college — implying that he is to be admired. The noisy music is also highly charged when Kabir Singh goes on the rampage, once again underscoring this glamour. Also conspicuous is the respectful responses he receives from everyone including the women, the associates always around attentive to his smallest whim. When he is held by the police and chided for smoking in their presence he continues to do so without being penalised. Kabir Singh, it can be argued, emerges as someone exercising feudal authority, seemingly out of place in cosmopolitan Hindi cinema but at home in the Telugu milieu. Andhra is the region in South-India with the greatest incidence of landed wealth. Land relationships are different from those under capitalism in that they are not contractual but create all-round dependencies and subservience; landowners are like absolute monarchs within their territory. Even the officials of the state fawn upon feudal landlords because of the political influence they exercise. Kabir Singh is a ‘brilliant doctor’ where Hindi films might have ‘inventor’ (3 Idiots) or ‘fund manager’ (Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara). The allure in the ‘doctor’ can be traced to medical graduates fetching the highest dowries in feudal Andhra. A key difference between Devdas and Kabir Singh is the latter’s desirability to women. The very first image in the film shows him in bed with an unknown young woman. He pursues the heroine Preeti Sikka (Kiara Advani) as if there was no possibility of her saying no to him but there is also the feeling deliberately created that he can have any woman he desires. This motif of the hero not fearing rejection is familiar and Shammi Kapoor clowned his way confidently after the heroine in films like An Evening in Paris (1967). Popular films earmark hero and heroine as only for each other by making the audience pair them off through filming/editing strategy. Never is the issue of who is to be paired off with who left in suspense. The hero’s confidence in his sexual desirability therefore rests in his knowing about the ‘pairing-off’. But Kabir Singh is different in that he is made the glamorous object of universal feminine desire and never made to doubt it. When he sets about wooing Preeti, she is in dread of him initially but he forces his attentions upon her continually, warning everyone else that she is only for him. But this encounters no resistance from her side and he ultimately seduces her. What should be disconcerting here is the unfairness of his project, as one-sided as that of the villains in Pink (2016). That film, to remind the reader, was focussed on the woman’s right to say ‘no’. Preeti eventually marries someone else due to parental compulsion and Kabir Singh takes to drugs, but his allure remains intact. A celebrity patient of his, an actress, also falls in love after being initially agreeing to a ‘no-strings relationship’. But even his failure to win Preeti is only temporary because he gets her at the end and the child inside her is his. It is evidently impossible for someone as authoritative as Kabir Singh to suffer Devdas’ fate. Kabir Singh should rightly be shunned but it is turning out to be a super hit among young audiences composed of both sexes. Looking at some youth films that became blockbusters – Bobby (1973), Ek Duuje Ke Liye (1981) and Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak (1988) – one finds the protagonists to be fragile, not even capable of defending themselves. Youth films are usually about rebellion and that is true of the films of James Dean (Rebel Without a Cause, 1955) and Marlon Brando (The Wild One, 1953) as well but in Indian youth films rebellion is manifested entirely in who the protagonists wish to marry. But considering that popular films are set in a world where family and romance are the key aspects and socio-political aspects rarely play a part, rebellion-through-romance should be treated as metaphor, ie: that it points to socio-political implications even though it does not invoke them explicitly. In Bobby, for instance, it points to the class differences between Mr Nath and Jack Braganza. Kabir Singh’s treatment of women should also be treated as a metaphor implying a world beyond family relationships. Kabir Singh is a ‘rebel’ in that he wishes to marry someone whose family is averse to the idea, but this goes along with his doing everything else without meeting resistance from his family, friends or even the law. While he often articulates untenable positions, never are they contradicted or counter-arguments. In one sequence, after his disappointment with Preeti’s marriage, he urinates on the terrace of his friend’s apartment, the latter’s family not taking exception – “that’s his way and it should be allowed,” is the indulgent impression. Given that each act of Kabir Singh spells domination over others, his rebellion should be interpreted socio-politically, as a eulogy of those breaking social codes simply because they can. Conventions and codes are for weaklings, is the message. The first sense anyone gets in a democratic society is that one cannot have one’s way even if one believes he or she is right, since right and wrong have to be tested in the public space and duly judged as such. Kabir Singh contradicts this notion by making its protagonist immune to such processes and its success makes it seem that there is an aspect immensely attractive to Indians (especially the young) in personal authority exercised unchecked. One cannot imagine a film like Kabir Singh made in another country and this leaves us wondering if there is not something today that makes Indians favour the ‘might is right’ maxim. Kabir Singh suggests that getting one’s way without opposition can itself be immensely glamorous in today’s milieu and this valorisation of brutal strength has implications in the political space. Those who are powerful can do what they wish unchallenged, even if their action is in fact unjustified and the public that responds positively to Kabir Singh will not be averse to it. MK Raghavendra is a film scholar and author of seven books including The Oxford India Short Introduction to Bollywood (2016). He is deeply interested in social, political and cultural issues in India, an interest that informs his books on film.

Kabir Singh should rightly be shunned but it is turning out to be a super hit among young audiences composed of both sexes.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)