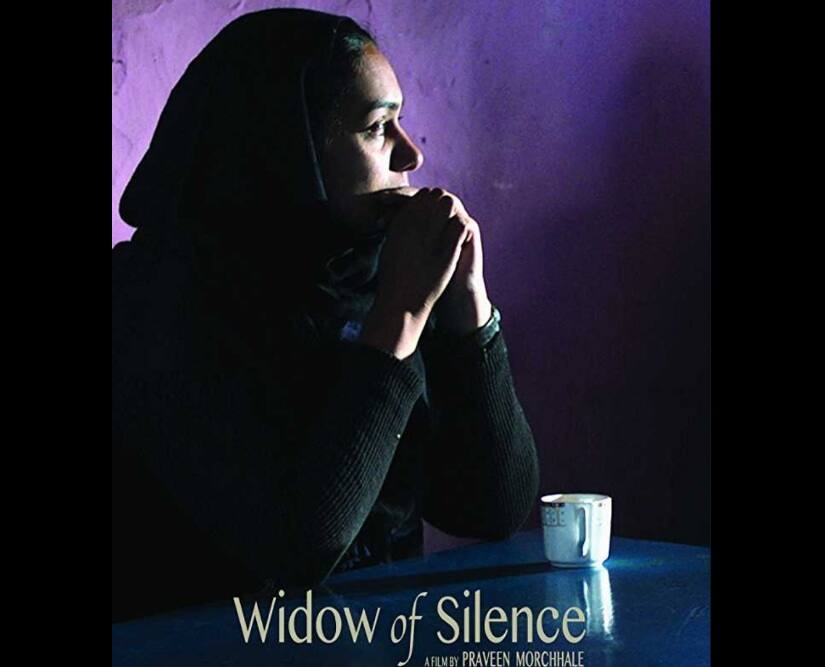

Film critic Roger Ebert spoke of cinema as the most powerful empathy machine in all the arts, one which helps us imagine more intensely than the other forms what it would be like to live someone else’s life; to know and experience, even if for a short while, how it feels to belong to a different race, class, gender or time. Cinema’s audio-visual nature has the innate power to generate the kind of identification and intimacy that is capable, Ebert believed, in its best moments, of turning us into better people. Focusing on one of the medium’s greatest virtues, the 48th edition of the International Film Festival Rotterdam (IFFR) developed its formidable programme around the theme of emotion. With its motto of ‘Feel IFFR’ appearing along with its tiger logo on posters, flags and advertisements all around the city and adorning the various festival venues, IFFR 2019 chose to showcase through its multiple segments, features and programmes, the visual image’s power to express and evoke emotion and to explore, as festival director Bero Beyer puts it in his Foreword to this year’s catalogue, “the importance of the cinematic experience as a way to find meaning in our existence…” [caption id=“attachment_6027911” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Poster of Widow of Silence. Image via Twitter/@CinemaRareIN[/caption] From works that explored the wonder produced by cinema giving it a tangible, physical form through toys made out of old 35mm film reels in a small village in Murshidabad (That Cloud Never Left) to those representing the anger and desperation of the half-widows in Kashmir (Widow of Silence) and even those that captured the universality, freedom and ardour of Gabriel García Márquez’s fiction (Sea of Lost Time), a variety of films from India were presented at IFFR 2019. In keeping with the overarching theme of this year’s edition, they managed to probe and uncover new ways to understand and convey human emotion but also, significantly, to push the boundaries of structure and form. This last is an aspect particularly relevant to IFFR given its traditional embracing and fostering of more experimental and innovative approaches to cinema and the visual arts in general. Yashaswini Raghunandan’s That Cloud Never Left and Gurvinder Singh’s Sea of Lost Time had their world premieres at IFFR this year. Raghunandan’s film, shot over a three-week period in Daspara in Murshidabad dives into a world of endless stories where children look for magic rubies in the forest, a buzzing television anticipates the appearance of a blood moon and toy sellers create toys out of cinema. Occupying a space somewhere between fiction and documentary, Raghunandan’s film, which she calls her “love letter” to the medium, engages with cinema both in terms of its history and form in a very real way. While a narrative around the rural space that she captures so intimately unfolds slowly, colourful bits of film that are used for the toys fill the screen and songs and dialogues from recognisable Indian films are periodically heard. Her images seem almost tactile and Raghunandan taps into themes of labour and craftsmanship not only through the shots of dye-stained hands delicately and yet rhythmically assembling the toys but also by tracing her story back to a culture of scrap where old discarded film is taken apart by tools only to be recycled and given new shape as toys which will continue to entertain people in still newer ways. It is a testament to the immense power of cinema which even as it changes form does not lose its ability to give joy or to generate employment for scores of people. [caption id=“attachment_6028001” align=“alignnone” width=“925”]  A still from The Cloud That Never Left which screened at The Rotterdam Film Festival. Image via Twitter/@AldoPadillaP[/caption] Gurvinder Singh’s 45-minute Sea of Lost Time is ‘an unfinished film’. An FTII-produced graduation project for acting students that Singh was invited to direct and that was stopped midway following a controversy around the appointment of Gajendra Chauhan as the chairman of the institute in 2015, Sea of Lost Time screened at IFFR under a programme entitled ‘Laboratory of Unseen Beauty’. This section was dedicated to ‘ruin films’ or works that could not be completed as planned, for reasons ranging from political interference and opportunism to the sudden death of key figures involved but were nonetheless given a new life for the purpose of presentation. Singh who had wanted to adapt elements from Marquez’s shorter fiction to an Indian setting for a while chose a host of colourful characters plucked from different stories and decided to set his film near the sea, noticing how important water was to Marquez’s narratives. The film however developed as a theatre workshop and with its actively non-realist approach looks and feels like a play which was shot on camera. Themes of dreaming and wakefulness, greed and betrayal are all touched upon while an exquisite rendition of a song translated from Pablo Neruda’s Alberto Rojas Jiménez Comes Flying ties the many fragmented stories together. Ridham Janve’s The Gold-Laden Sheep & the Sacred Mountain which had screened at the Mumbai Film Festival last year had its international premiere at IFFR. A slow, ruminative film about the sheep-rearing Gaddi community of Himachal Pradesh and the myths and legends that have prevailed within it for generations, the film employs members from the community in its cast and depicts the harshness of the terrain which they are forced to navigate daily. The community’s deep ties to the land are explored which pertain not just to subsistence but are also strangely mystical. On the other hand, the film offers a profoundly humbling vision of man’s place in the natural world which he is powerless to control or manipulate for his own selfish ends. Praveen Morchhale’s Widow of Silence and Devashish Makhija’s Bhonsle, both of which were shown at the Busan International Film Festival last year, travelled to IFFR. The former looks at the politically volatile state of Kashmir and the plight of its women whose husbands have been taken away for reasons unknown to them and who are now left to fend for themselves and those dependent on them. Theatre actress Shilpi Marwaha offers a robust central performance as the half-widow who must withstand devious forces even as the last traces of freedom and the possibility happiness slowly slip away from her. Morchhale’s film begins and ends memorably, opening with the powerful image of an old woman who has been silenced by shock and trauma being bound by rope to a chair and closing on a clever and vital act of rebellion with its long-suffering half-widow ultimately deciding to turn an oppressive bureaucratic system on itself. Bhonsle which takes the immigrant issue and its attendant insider-outsider crisis head on also sees its eponymous retired constable pushed to take matters into his own hands. The sustained tension and sense of outrage at the predicament of the common man, along with Makhija’s very productive association with Manoj Bajpayee, all of which had resulted in the explosive Taandav in 2016, find their true and complete realisation in this film. [caption id=“attachment_6027981” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Manoj Bajpayee in Bhonsle. Image via Twitter/@Apurvasrani[/caption] Also at IFFR 2019 were The Blood of Stars, a short video essay by the New Delhi-based Raqs Media Collective exploring the uses of iron, and Srinagar, an installation by artist Praneet Soi combining dual slide projection, papier mâché tiles and wall drawings to present a view of Kashmir distinctly separate from the distorted ways in which it has been portrayed by the media. The Blood of Stars, through the use of poetic text, identifies iron as the element uniting mortal and celestial beings and locates its importance in human history and evolution. Soi’s Srinagar on the other hand was one of 11 installations in Blackout, an exhibition focused on historical memory and amnesia and the unearthing of deliberately forgotten histories through personal narratives. While the artistic history of Kashmir was represented through the motifs on the papier mâché tiles which can be traced back to hundreds of years of travel and migration of people from Iran and Central Asia to northern India, the realities of the political scenario of the state and its misrepresentations in the media were depicted through the slideshows and wall drawings. India was thus represented at IFFR this year through an eclectic mix of films and projects that explored fresh stories and new perspectives while also extending the limits of form in inventive ways, and thereby managed to find a home for themselves within the festival’s expansive framework and vision. With the year begun on such an optimistic note, one can certainly hope that more exposure and travel await these films and their makers in the months to come.

Indian filmmakers managed to find a home for themselves within the Rotterdam Film Festival’s expansive framework and vision, setting the pace for the year

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)