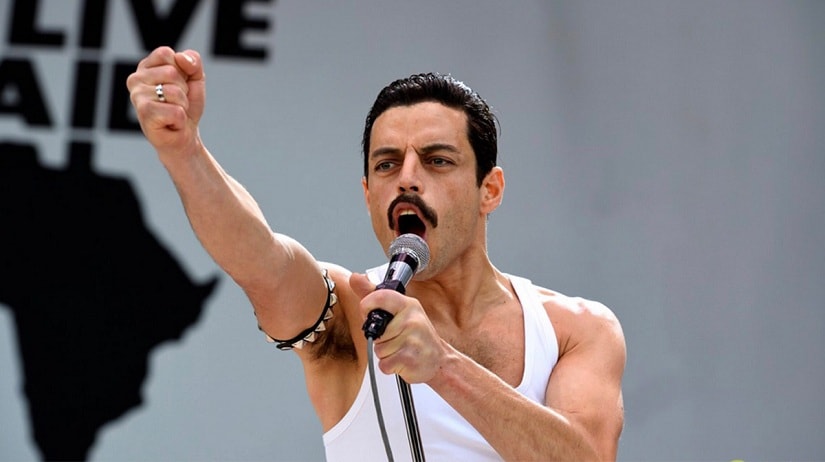

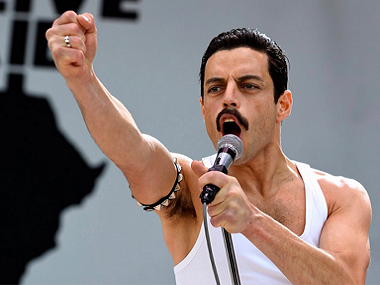

The Freddie Mercury biopic, Bohemian Rhapsody, made me recall many dramas about singers, but for different reasons. I enjoyed this film, flaws and all. It didn’t bother me much that Freddie’s decision to pursue a solo career is treated by his fellow band mates with the kind of incredulity that suggests they’ve never heard of John Lennon. It didn’t bother me much that Freddie’s gay friends (and boyfriend) are all painted with the same unsympathetic brush. It didn’t bother me much that the songwriting seems so easy, that hits seem to roll off the practice sessions like magic. All because the music kept coming. Music I knew. Music I grew up with. Music that, combined with nostalgia, reduced me to an emotional puddle. One huge plus can compensate for many smaller minuses. [caption id=“attachment_4474203” align=“alignnone” width=“825”]  Rami Malek as Freddie Mercury in a still from Bohemian Rhapsody[/caption] It’s very different while watching the biopics on, say, Édith Piaf. The most famous one, of course, is Olivier Dahan’s La Vie en rose (2007), with Marion Cotillard as Piaf. There’s also Claude Lelouch’s Édith et Marcel (1983 ), which focuses on the relationship between Piaf (Évelyne Bouix) and the already-married boxer Marcel Cerdan (played, curiously, by his real-life son, Marcel Cerdan Jr; this is surely the only time a son has re-enacted the love affair that broke up his parents’ marriage). Vincent Canby, in the New York Times, sniffed that the director “doesn’t just photograph Edith and Marcel. Their every appearance in this film amounts to a celebration, which often makes the camera so giddy that it sweeps in great dizzy circles around them…”

You get a sense of this style in the clip above (it concludes the film), but unlike the Times critic, I welcomed this giddiness, this sense of “staging” around the song. Because the song itself is not known to me. It doesn’t invoke a fond smile or nostalgia (like the songs in Bohemian Rhapsody did). While films themselves work differently for different people, this truth is even more pronounced in the case of biopics. If we know the subject, if we know his/her works, then even a problematic production like Bohemian Rhapsody can become quite pleasurable. If not, there’s additional pressure on the film to work as a film, to seduce us with its cinematic aspects. The song in Édith et Marcel didn’t sweep me away in “great dizzy circles”, but I was grateful at least the camera did. Another biopic that’s making waves this season (and which I saw at the Venice Film Festival) is Julian Schnabel’s At Eternity’s Gate, which imagines the last few years of the life of Vincent van Gogh (Willem Dafoe). Schnabel is a painter himself, and he details the creation of (or the circumstances behind) van Gogh’s works like A Pair of Shoes and Portrait of the Postman Joseph Roulin. The director does on film what the Post-Impressionists did on canvas. The fevered colours are mirrored by the feverish camerawork, with shivering frames. The multi-layered coats of paint (pal Paul Gauguin tells van Gogh, “Your surface looks like it is made of clay. Looks more like a sculpture than a painting”) become overlapping voices and superimposed images. Schnabel doesn’t just showcase an artist and his art. He creates an art installation about the insides of van Gogh’s head. But what about the man himself? van Gogh, for me, is a curious case. I cannot claim I know his paintings as intimately as Queen’s music. And yet, given how famous his paintings are – or, indeed, his style is – some amount of familiarity does exist. So the various biopics about his life become various ways to approach the man. Vincente Minnelli’s _Lust for Life (_1956), with Kirk Douglas as the tortured artist, is a good, old-fashioned, Hollywood biography, dramatising key episodes of van Gogh’s adult life (the ear-slicing, the breakup with Gaugin, the relationship with his brother Theo, the time spent in a mental asylum). At the other end, we have Maurice Pialat’s Van Gogh (1991), which restricts the action to van Gogh’s final months in Auvers-sur-Oise. In other words, a passage that occupied some ten minutes in Minnelli’s film is stretched to two-and-a-half hours here. As a result, we spend less time with the paintings, more time with the people. One of the problems I had with Bohemian Rhapsody is that the people around the protagonist, Freddie Mercury, are reduced to one-note caricatures. Van Gogh is different. It gives us a full sense of the painter and his brother (who supports him financially) and the latter’s wife (Johanna), even more than Robert Altman’s Vincent & Theo (which released in 1990, a few months before Pialat’s film) did. In The New Yorker, Pauline Kael summed up, succinctly, the core of the Altman film. She said, we get the “interpretation of the bond between the brothers – the bond that helps to keep Vincent alive while it tears Theo apart… Their bond of love of art is also a bond of shared rage at the world of commerce.”

How much nicer Bohemian Rhapsody would have been had it given us a similar sense of the warp and weft of the protagonist’s environment, and not just the narrative threads of his life. In Pialat’s film, Johanna and Theo keep arguing about Vincent. At one point, she says, “We can’t do anything except relieve our own guilt. Like charity, that makes the donors feel good. Those 50 franc bills… they relieve you more than him.” But later, she bursts out, “[If you stopped giving him money] He’d get a job like everyone else. I’ve known men as talented as he, who wanted to live off their art. They took jobs. Like everyone. Real jobs. Being an artist is a luxury. You must be able to afford it.” Luckily, in Bohemian Rhapsody, the music transports you to a place your critical faculties remain suspended. The art on screen may not be much, but oh, the art behind it! Baradwaj Rangan is Editor, Film Companion (South).

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)