It is likely you may not know of Anthony Powell, who passed away at the age of 85 last weekend, but you would likely be intimately familiar with his work. Like me, you might have watched the 1978 film Death on the Nile multiple times, and savoured its precise and sumptuous costumery that brought alive Agatha Christie’s murder mystery. Powell won an Oscar for costume design for the film, one of three Oscars that he won in his lifetime in addition to several BAFTAs and many other accolades across his incredible career.

Spanning almost four decades (the mid-1960s through the mid-2000s), Powell’s body of work looks like a capsule of Hollywood history.

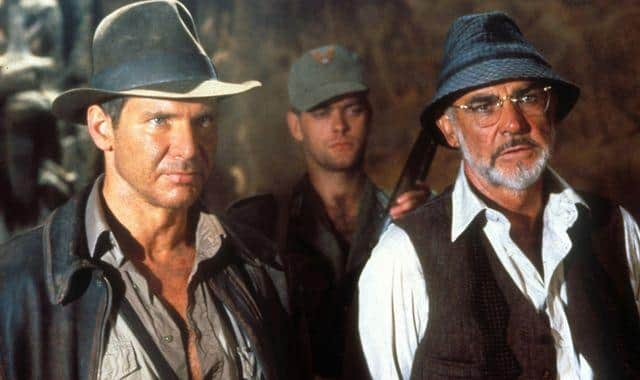

From the subtle to the ostentatious, Powell’s talent was visible across a wide spectrum of films. He was, in fact, the costume designer behind many iconic films and Broadway plays including films with unforgettable costumes such as Indiana Jones Temple of Doom and The Last Crusade, Steven Spielberg’s Hook, Disney’s live action film 102 Dalmations, and Broadway versions of Sunset Boulevard. He clothed characters played by most major stars over the decades, clothes that defined their stardom, whether it was Harrison Ford and his fedora as Indiana Jones or Glenn Close and her flamboyant ostrich feathers as Cruella de Vil, or Maggie Smith and her jaunty hats in the several films they did together. But perhaps his most loved works were the period films, that took you straight to another time and another place like a time machine. Period films are challenging to do (even though they are more likely to win awards or recognition for costume than contemporary films) because of the danger of costumes becoming either a caricature or too much like a documentary film. Powell was often called the “master of period detail,” fastidious about detail right down to the “correct period underwear”, who managed to strike this balance between being realistic and artistic. With his craft, he transported you. Death on the Nile (now being remade by Kenneth Branaugh, and scheduled for a 2022 release) perhaps is the more celebrated of his period films for its magnificent costumes showcasing 1930s Hollywood glamour. In the film (a murder mystery aboard a pleasure cruise on the river Nile), Powell was charged with costume design for a high-power ensemble cast – Peter Ustinov, David Niven, Bette Davis, Maggie Smith, Angela Lansbury, and Mia Farrow amongst them – set against the dusty landscape of Egypt and the River Nile. One of the defining characteristics of the film is the colour palette that Powell chose for the costumes – whites, creams, beiges, taupe - desert tones against the dusty brown and blues of its Egyptian backdrop. It is astounding how many kinds of white and ivory and cream and beige he was able to show the viewer, through texture, through fabric ranging from lace to linen and silks and fur, and through clever detailing and silhouettes. [caption id=“attachment_9552361” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Still from Death on the Nile (1978)[/caption] Not only did he manage to showcase a range within one colour scheme, he was able to make each character distinct from the other, even within this palette in which everyone could just have ended up looking like everyone else in a 1930s fashion show. For example, he gives the wealthy American socialite played by Bette Davis an Edwardian wardrobe of lace. Her nurse and attendant played by Maggie Smith wears boyish, queer-influenced outfits, even a tuxedo in the evenings. An ageing romance novelist played by Angela Lansbury gets to wear fantastical caftans and jewelled turbans as if she is still famous, while her subdued daughter in contrast is defined by soft feminine chiffon dresses with flouncy sleeves. Powell brought each character to life by imbuing them with more than just a costume, but with taste and style, and importantly - an individuality. He had a deep understanding of how internal qualities of a character could be expressed through clothes and accessories to create a persona. He also understood how costumes helped actors get into character. In an interview, Powell says, “Our job is to make it easier for the actors or singers to do their job”. It is also, he observes, to bring closer the inherent qualities of the actor playing the role, with what’s in the script to a point where they merge perfectly. Powell’s insights on his craft are quite wonderful to listen to, as I found in this small snippet where he talks of costuming for another shimmering Agatha Christie film, Evil Under The Sun. He appears to have been a hands-on costumier, steeped in the script, even using the blank page on the left to draw his first ideas as he read the script in solitary confinement. Powell says of creating each frame, “It’s like doing a painting. It has to make a picture”. [caption id=“attachment_9552371” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Still from Evil Under The Sun[/caption] Powell’s stories are reminiscent of a time when films were made luxuriously with time and attention (he had a whole year to prepare for a film in the 1970s, as compared to two weeks in the 2000s) – and even an extra scene at the last minute meant trouble! The story goes that when a new scene was suddenly added to Death on the Nile on location in Egypt, Powell had no cloth left to create anything new for the scene. In a situation of spirited jugaad, he repurposed a “a grubby tea towel covered in grease and garlic and olive oil” (being used by the tailor’s mother who was cooking paella on board the ship) into a chic striped waistcoat for Farrow’s character. He boiled it four times to get rid of the grime and get the linen tea towel to regain its original luster, but he could not fully remove the smell of garlic! Another fabulous story is the clever innovation in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. When Sean Connery refused to wear a tweed suit in the heat of Petra (where the shoot had been shifted) – but the script had to have him wear a tweed suit through the film – Powell thought of screen printing a tweed print on a cotton voile suit instead! [caption id=“attachment_9552391” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Still from Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade[/caption] Fabrics of all kinds are a recurring theme in Powell’s oeuvre. He says, “All through my career, I’ve collected interesting fabrics knowing that one day they would solve a problem, which they always do. That one day they’ll be perfect for something”. Also recurring are fabulous hats. Oh, the hats. From turbans to top hats to bonnets and feathers, cloches and skull caps, tricorn pirate hats, bowler hats, Powell was a champion of glorious headgear. The importance of accessories overall in creating a memorable character, whether it was collars, hats or neckpieces, was never lost on Powell. [caption id=“attachment_9552401” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Still from Evil Under The Sun[/caption] Powell’s work had an influence beyond cinema, in fashion. The relation between fashion and cinema has been tricky, with one constantly trying to stay apart and distinguish itself from the other. According to writer Mark O’Connell, Powell noted that, “I once realised that whenever I did a period film that had interesting or amusing hats, one or two of those would always appear in the next Paris collections.’ Powell leaves behind a feast of a legacy, with delicious costumes and unforgettable designs. He gave generations of film viewers great pleasure, evoking feelings without saying a word, and so very often finding that sweet spot of perfect harmony between the story and the style.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)