New Delhi - Hardening food inflation is making everyone cringe. Though many analysts have dismissed the spike in prices of daal and vegetables as seasonal, there is no respite in sight in the short run. Prices of pulses may continue to climb, especially in the upcoming festival season, as there is still no mechanism put in place by the government to procure from Indian farmers and sell this commodity to control abrupt price fluctuations, despite an increase in acerage of pulses’ sowing. Prices of vegetables and fruits are also unlikely to subside anytime soon, partly because of traditional spikes in the northern parts of the country throughout the monsoon. Another reason for the further rise is the reluctance of state governments to dismantle APMCs which encourage middle men and push up prices for end consumers. Maharashtra seems to have moved ahead with APMC dismantling while Delhi is the only other state which has scrapped this mechanism. In short, food inflation is not going away in the short term and daal-roti will continue to be dearer. [caption id=“attachment_2904020” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]

Reuters[/caption] In fact, the pulses’ headache has now grown to such an extent that

the Competition Commission of India is now

planning to study their pricing. A

report

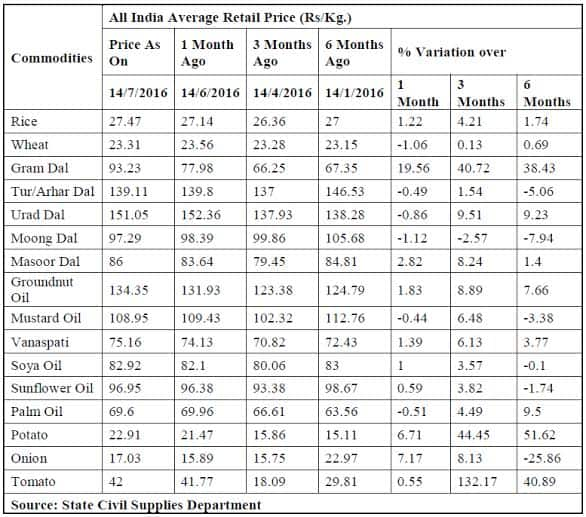

in the DNA newspaper says pulses could cost up to Rs 300 a kg soon. According to data compiled by the government, the biggest price increase has been seen in tomatoes, which were retailing at just about Rs 18 a kg in April but had risen to Rs 42 by July 14. That is an over 132 percent increase. The humble chana daal is also making Indians cry. Billed as one of the cheapest sources of protein and among the cheapest pulses in the country, this daal saw a massive spike in retail prices by almost 20% in a month and by over 40% in the last three months. Not just pulses, potatoes are also on fire with prices up by almost 45 percent in the last three months and by over 50 percent in the last six. These percentages have been derived from data given in the Lok Sabha this week by Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution Minister Ram Vilas Paswan. So chana daal was retailing at an average price of Rs 93.23 per kg on July 14 against Rs 66.25 per kg on April 14 while aloo was at Rs Rs 22.91 versus Rs 15.86 per kg in the same period.

Reuters[/caption] In fact, the pulses’ headache has now grown to such an extent that

the Competition Commission of India is now

planning to study their pricing. A

report

in the DNA newspaper says pulses could cost up to Rs 300 a kg soon. According to data compiled by the government, the biggest price increase has been seen in tomatoes, which were retailing at just about Rs 18 a kg in April but had risen to Rs 42 by July 14. That is an over 132 percent increase. The humble chana daal is also making Indians cry. Billed as one of the cheapest sources of protein and among the cheapest pulses in the country, this daal saw a massive spike in retail prices by almost 20% in a month and by over 40% in the last three months. Not just pulses, potatoes are also on fire with prices up by almost 45 percent in the last three months and by over 50 percent in the last six. These percentages have been derived from data given in the Lok Sabha this week by Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution Minister Ram Vilas Paswan. So chana daal was retailing at an average price of Rs 93.23 per kg on July 14 against Rs 66.25 per kg on April 14 while aloo was at Rs Rs 22.91 versus Rs 15.86 per kg in the same period.

Paswan said in a written reply that average retail prices of tur and moong among pulses; mustard, soya and sunflower in edible oils; and onion in vegetables declined during the last six months. “While there has been increase in the prices of gram and urad dal in pulses, groundnut and palm oil in edible oils and potato and tomato in vegetables, details is at Annexure I. Rise in the prices of essential food items are due to factors such as shortfall in production owing to adverse weather conditions, increased transportation costs, supply chain constraints like lack of storage facilities and hoarding and black marketing.” The minister went on to list various steps taken by the Centre to mitigate price increases of these food items but the moot point is lack of any long term planning in this regard. Sudhir Panwar, President of Kisan Jagriti Manch, points out the absence of a long-term plan for pulses’ procurement. “Around October, when there will be pulses available for procurement, the government must come up with a comprehensive plan. Food Corporation of India has little expertise in procurement or storage of pulses… the government must offer remunerative prices for pulses’ procurement so that farmers get incentivised to grow more,” he said. India’s pulses’ production has been lagging demand year on year, with the gap being filled by imports. Panwar gives the example of Madhya Pradesh, where a farmers’ cooperative called Small Farmer Agri Consortium (SFAC) purchased arhar and moong daals at Rs 90 per kg this year against a government MSP price of about Rs 40-50 per kg. Such incentives will mean increased pulses’ cultivation and therefore narrowing of the demand-supply gap. This will then obviously cool prices. But D K Joshi, Chief Economist at Crisil, says food inflation should cool this fiscal. “We think CPI inflation will average 5% this fiscal, which is in line with the target set by RBI,” he said. Joshi said area sown under pulses has increased and import contracts are being tied up so that there should be a moderation in the price of pulses in the next few months. In a report in November last year, Crisil had said that a rise in prices of pulses can have a huge impact on inflation expectation and can influence wage-price negotiations. This report had listed out areas where the government needs to focus such as setting medium to long term target of attaining self-sufficiency in pulses. The Indian Institute of Pulses Research has forecast demand at 39 million tonnes by 2050, which will require production to grow at an annual rate of 2.2%, compared with the 0.9% seen in the last decade. Then, raising the irrigated area under pulses and sustained efforts to prevent hoarding and maintaining price stability are also key initiatives. On vegetable price spike, it seems better mechanism for distribution and retailing is the only way for end consumers to get reasonable prices. Agricultural markets across the country are regulated at the state-level Agricultural Produce Marketing Committees (APMC) Act and farmers have to mandatorily sell their produce at APMCs.

This piece

says creating competition to the existing APMC mechanism will go a long way in controlling food inflation. It quotes the Economic Survey of 2014-2015 to say that “The levies and other market charges imposed by states vary widely. Statutory levies/mandi tax, VAT etc are a major source of market distortion. Such high level of taxes at the first level of trading has significant cascading effects on the prices as the commodity passes through the supply chain.” In short, lessen the role of middlemen for farmers to sell directly to consumers. Maharashtra has lead the way, other states also need to examine the feasibility of this.

Paswan said in a written reply that average retail prices of tur and moong among pulses; mustard, soya and sunflower in edible oils; and onion in vegetables declined during the last six months. “While there has been increase in the prices of gram and urad dal in pulses, groundnut and palm oil in edible oils and potato and tomato in vegetables, details is at Annexure I. Rise in the prices of essential food items are due to factors such as shortfall in production owing to adverse weather conditions, increased transportation costs, supply chain constraints like lack of storage facilities and hoarding and black marketing.” The minister went on to list various steps taken by the Centre to mitigate price increases of these food items but the moot point is lack of any long term planning in this regard. Sudhir Panwar, President of Kisan Jagriti Manch, points out the absence of a long-term plan for pulses’ procurement. “Around October, when there will be pulses available for procurement, the government must come up with a comprehensive plan. Food Corporation of India has little expertise in procurement or storage of pulses… the government must offer remunerative prices for pulses’ procurement so that farmers get incentivised to grow more,” he said. India’s pulses’ production has been lagging demand year on year, with the gap being filled by imports. Panwar gives the example of Madhya Pradesh, where a farmers’ cooperative called Small Farmer Agri Consortium (SFAC) purchased arhar and moong daals at Rs 90 per kg this year against a government MSP price of about Rs 40-50 per kg. Such incentives will mean increased pulses’ cultivation and therefore narrowing of the demand-supply gap. This will then obviously cool prices. But D K Joshi, Chief Economist at Crisil, says food inflation should cool this fiscal. “We think CPI inflation will average 5% this fiscal, which is in line with the target set by RBI,” he said. Joshi said area sown under pulses has increased and import contracts are being tied up so that there should be a moderation in the price of pulses in the next few months. In a report in November last year, Crisil had said that a rise in prices of pulses can have a huge impact on inflation expectation and can influence wage-price negotiations. This report had listed out areas where the government needs to focus such as setting medium to long term target of attaining self-sufficiency in pulses. The Indian Institute of Pulses Research has forecast demand at 39 million tonnes by 2050, which will require production to grow at an annual rate of 2.2%, compared with the 0.9% seen in the last decade. Then, raising the irrigated area under pulses and sustained efforts to prevent hoarding and maintaining price stability are also key initiatives. On vegetable price spike, it seems better mechanism for distribution and retailing is the only way for end consumers to get reasonable prices. Agricultural markets across the country are regulated at the state-level Agricultural Produce Marketing Committees (APMC) Act and farmers have to mandatorily sell their produce at APMCs.

This piece

says creating competition to the existing APMC mechanism will go a long way in controlling food inflation. It quotes the Economic Survey of 2014-2015 to say that “The levies and other market charges imposed by states vary widely. Statutory levies/mandi tax, VAT etc are a major source of market distortion. Such high level of taxes at the first level of trading has significant cascading effects on the prices as the commodity passes through the supply chain.” In short, lessen the role of middlemen for farmers to sell directly to consumers. Maharashtra has lead the way, other states also need to examine the feasibility of this.

Veggie, daal prices likely to hit roof again as middle-men raj continues

Sindhu Bhattacharya

• July 20, 2016, 12:08:51 IST

On vegetable price spike, it seems better mechanism for distribution and retailing is the only way for end consumers to get reasonable prices

Advertisement

)

End of Article