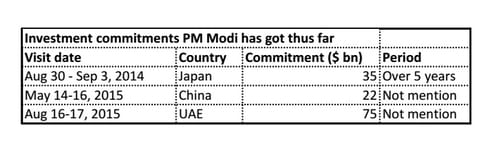

The proposal to create $75 billion fund jointly between India and the UAE is being seen as a major victory of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s just concluded foreign visit. This corpus, the government hopes, will fill the wide funding gap in India’s infrastructure sector to develop railways, ports, roads, airports and industrial corridors. If indeed the proposal works out in India’s favour, this can give a major boost to the country’s fund-starved, poorly managed infrastructure sector. While the government lacks the fiscal capacity to pump in large-scale investments and the private sector is reluctant to put money on the table, foreign money is key to develop the infrastructure sector. But before celebrating the $75 billion commitment, one must remember that huge commitments have rarely translated into actual action in the past. At least that is what evidence from the past has taught us in India. It’s easy to make announcements about billions of dollars that are to be invested but when it comes to putting the money on the table, investors tend to look at the ground realities and the chances of getting their money back with a higher return. [caption id=“attachment_2396896” align=“alignleft” width=“380” class=" “]  Image courtesy: PTI[/caption] In India, most promises have remained just that in the past. As Firstpost noted in an earlier article , this is one reason why real growth has eluded the country all these years. An excellent study conducted by rating agency, CARE, gives a true picture. According to the study, the actual investments made across all industries in the last five years stand at Rs 2.71 lakh crore, while Rs 31.93 lakh crore investments were proposed across 11,784 projects in the country. In other words, this means only 8.4 percent of the committed funds have actually been invested. There has been a continuous slowdown in the proposed amount and number of investments over the last five years with the former declining from Rs 15.4 lakh crore in 2011 to Rs 4.05 lakh crore in 2014 and further to Rs 1.5 lakh crore for the five months of 2015. Similarly, the number of investment proposals declined to 1,843 in 2014 as against 4,336 in 2011. During the first five months of 2015, number of proposals stood at 826, compared with 868 in the corresponding period of 2014, the CARE study shows. What has acted as a hurdle between the promises and actual actions? The biggest problem lies in the difficulties in getting environmental clearances on time and securing go ahead braving the bureaucratic red-tapes. Over the years, several projects got stalled on account of clearance issues, mainly in the infrastructure sector. When projects get delayed, the cost burden of the companies increases since there is a cost over-run on these projects.  This impacts the cash flows and repayments to banks, eventually forcing companies to seek financial restructuring of the loan. If one looks at the restructured loan portfolio under the corporate debt restructuring (CDR) mechanism, the biggest chunk is restructured loans for infrastructure. Rejigged loans from iron and steel and infrastructure together constitute almost half of the total stock, as of end June, about Rs 1.1 lakh crore in absolute number. Due to the difficult environment to operate and also because of the inability of banks (loaded with bad debt) to lend further, the number of fresh projects too has declined sharply in the recent past. According to the data from Centre for Monitoring India Economy (CMIE), at an absolute level, the number of project announcements in the first quarter of 2015-16 has gone down by 53 percent compared with the previous quarter. Of course, the CMIE adds that the number of stalled projects has come down in the recent months but this has to be seen in the backdrop of scrapped projects as well. Although scrapping unviable projects makes business sense one needs to understand the factors that led to this eventuality. According to CMIE chief Mahesh Vyas, new projects announced during April-June stood at Rs 1.2 lakh crore. Also, in the first quarter, the announcements of new government projects have seen a second straight quarter of decline. Vyas attributes the fall in stalled projects partly to the abandoned projects in the first quarter. Companies typically abandon projects when the project becomes unviable due to cost escalation due to prolonged delays or demand slowdown. Secondly, difficulties in acquiring land for industries have acted as a major deterrent to foreign investors. There has been no progress on the land acquisition bill in Parliament, where the Modi government has been successfully cornered by the opposition ploy to stall progress of reforms. The government needs to find its way around the opposition to get the land bill passed since it is crucial to get industries kick off their investment plans. Also, it is critical to go ahead with other large ticket reforms, labor and tax, in particular. Thirdly, the government’s flip-flops on the decisions taken earlier, including the taxation rules, and frequent judicial interventions in policy decisions have been a major turn off to foreign investors who wants to invest in the country. The government needs to offer some certainty to the investors and be consistent with its policies. No one wants to experiment with their money. The government has not been able to fulfil the high expectations it gave on fast-paced reforms and ease of doing business. Investors waiting for ‘achhe din’ have begun to get impatient and international rating agencies have begun sounding words of caution. On Tuesday, rating agency Moody cut India’s fiscal year 2016 GDP target to 7 percent from 7.5 percent earlier, noting the slow progress of industrial recovery in the economy. To be sure, the Modi government has indeed made efforts towards easing the process of doing business but how much of these efforts have been absorbed by bureaucracy at lower levels is doubtful. The point is unless there is a conducive environment to do business on the ground and make long-term investments, it is unwise to expect actual investments beyond tall promises. Billion dollar investment announcements surely catch headlines, but Modi must get the groundwork done by fast-tracking reforms. That is where India lacks as of now.

Modi has indeed made efforts towards easing the process of doing business but how much of these efforts have been absorbed by bureaucracy at lower levels is doubtful

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)