Indian public sector banks have been in bad shape for a while now, thanks to an overload of bad loans, which are close to topping Rs 3,00,000 crore. But the issue now is no longer about providing them with additional capital and giving them better leadership untainted by crony links. With the emergence of payment banks as a new competitive threat, public sector banks (PSBs) will be reduced to carcasses if they are not privatised or - in the alternative - downsized. Two PSBs are already close to the 10 percent mark on bad loans - which means they are walking zombies pretending to be vibrant banks. If bad loans are blighting their assets, soon payment banks will be stealing their low-cost deposit bases, as

State Bank Chairman Arundhati Bhattacharya said the other day

. This means their cost of funds will rise as competition for funds gets sharper, making it even tougher for them to provide for bad loans through higher profitability. [caption id=“attachment_2395416” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]

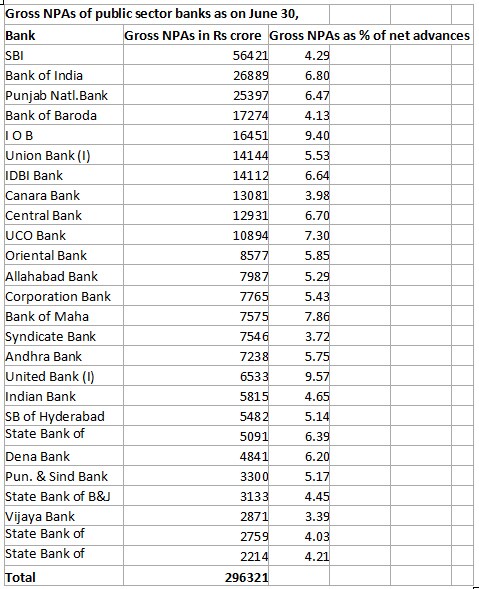

Reuters image[/caption] This is why privatisation – the P word that Narendra Modi has been unenthusiastic about - has to be brought back to the table as an option. If this isn’t done, in three or four years’ time he will have at least four or five stretcher cases on his hands. As at the end of June, just nine PSBs had gross bad loans below 5 percent of assets; four had non-performing assets (NPAs) in excess of 7 percent, and two of them were heading towards double-digits - Indian Overseas Bank and United Bank, with 9.4 percent and 9.6 percent respectively (see table). Modi should shudder at the prospect of having five Air Indias or BSNLs to feed from the public exchequer just when he is seeking re-election in 2019. Improved management and greater autonomy to boards will certainly improve matters, but may not eliminate the rot that has accumulated in the public sector banking system, which has been ruined by cronyism, excess manpower, and poor management. The truth is PSBs are high-cost monsters and they are also relatively poorly invested in technology vis-a-vis private banks. This means they not only need more capital for providing against bad loans, but also extra money for offering voluntary retirement schemes (VRS) to excess staff, and for investments in upgrading technology. PSBs are also psychologically ill-equipped to take the risks the future holds. The banking business is no longer a simple one of taking money from depositors and lending to corporates and individuals. A bank has to continuously invest in technology as it has to face new competition not only from other banks, but non-banks like payment wallets, gold loan companies, and even ecommerce players, who will become quasi-financial companies in due course.

Reuters image[/caption] This is why privatisation – the P word that Narendra Modi has been unenthusiastic about - has to be brought back to the table as an option. If this isn’t done, in three or four years’ time he will have at least four or five stretcher cases on his hands. As at the end of June, just nine PSBs had gross bad loans below 5 percent of assets; four had non-performing assets (NPAs) in excess of 7 percent, and two of them were heading towards double-digits - Indian Overseas Bank and United Bank, with 9.4 percent and 9.6 percent respectively (see table). Modi should shudder at the prospect of having five Air Indias or BSNLs to feed from the public exchequer just when he is seeking re-election in 2019. Improved management and greater autonomy to boards will certainly improve matters, but may not eliminate the rot that has accumulated in the public sector banking system, which has been ruined by cronyism, excess manpower, and poor management. The truth is PSBs are high-cost monsters and they are also relatively poorly invested in technology vis-a-vis private banks. This means they not only need more capital for providing against bad loans, but also extra money for offering voluntary retirement schemes (VRS) to excess staff, and for investments in upgrading technology. PSBs are also psychologically ill-equipped to take the risks the future holds. The banking business is no longer a simple one of taking money from depositors and lending to corporates and individuals. A bank has to continuously invest in technology as it has to face new competition not only from other banks, but non-banks like payment wallets, gold loan companies, and even ecommerce players, who will become quasi-financial companies in due course.

Banking will move towards mobiles and cashless payments, which will make the huge branch infrastructure of PSBs unviable, unless these are put to value-added use like selling financial products or even as pickup points for ecommerce purchases. Banks will have to manage multiple relationships with ecommerce sites and other vendors, even while their most bankable borrowers - big corporations - start raising money directly from savers. Put another way, banks are going to lose their best borrowers and best lenders (ordinary depositors) even while the old banking business model is under threat. In this scenario, the nimble HDFC Banks and ICICI Banks will leave their public sector counterparts far behind because the latter are less entrepreneurial than private banks. The Airtels and Vodafones will enter banking through the payment banking route, taking away many customers with them. Modi and his finance minister thus have two options - both difficult choices. They have to get legislation in place to privatise some public sector banks before they become complete basket cases. At least four of them currently have non-performing assets above 7 percent – a danger mark that indicates that the real situation may be even worse. At the very least, if the word privatisation is anathema to this government, it will have to legislate a golden share where majority voting rights remain with the government, but economic ownership and management can pass into private hands. Privatisation is vital not only to tank up on vital capital, but also to handle difficult labour downsizing issues and avoid the moral hazard of further increasing crony lending. The other option is to shrink the worst-performing public sector banks into narrow banks. Narrow banks have freedom to raise deposits, but their lending operations are either severely curtailed or restricted to investments only in triple A borrowers and the government. Right now, four banks – United Bank, IOB, Bank of Maharashtra, and Uco Bank – should be considered ripe candidates for narrow banking. The other thing to do is to force these banks to hive off their bad loans into a separate legal entity whose only job will be to retrieve what they can from borrowers. Here’s an idea: in the short run, let the government designate one public sector bank – say Indian Overseas Bank – as a bad bank and sell all the bad loans to it. IOB should focus all its energies on retrieving bad loans and focus only on deposit taking in its newly narrowed down brief. Both these options - narrow banking and hiving off bad loans into “bad banks” - can be done without legislation through regulatory action on the part of the Reserve Bank and support from the finance ministry. Modi and Jaitley have very little room to manoeuvre on public sector banks. It’s time to accept the inevitable and embrace the P-word. The alternative is multiple negative versions of the B word - bankruptcy, bailout and basket cases.

Banking will move towards mobiles and cashless payments, which will make the huge branch infrastructure of PSBs unviable, unless these are put to value-added use like selling financial products or even as pickup points for ecommerce purchases. Banks will have to manage multiple relationships with ecommerce sites and other vendors, even while their most bankable borrowers - big corporations - start raising money directly from savers. Put another way, banks are going to lose their best borrowers and best lenders (ordinary depositors) even while the old banking business model is under threat. In this scenario, the nimble HDFC Banks and ICICI Banks will leave their public sector counterparts far behind because the latter are less entrepreneurial than private banks. The Airtels and Vodafones will enter banking through the payment banking route, taking away many customers with them. Modi and his finance minister thus have two options - both difficult choices. They have to get legislation in place to privatise some public sector banks before they become complete basket cases. At least four of them currently have non-performing assets above 7 percent – a danger mark that indicates that the real situation may be even worse. At the very least, if the word privatisation is anathema to this government, it will have to legislate a golden share where majority voting rights remain with the government, but economic ownership and management can pass into private hands. Privatisation is vital not only to tank up on vital capital, but also to handle difficult labour downsizing issues and avoid the moral hazard of further increasing crony lending. The other option is to shrink the worst-performing public sector banks into narrow banks. Narrow banks have freedom to raise deposits, but their lending operations are either severely curtailed or restricted to investments only in triple A borrowers and the government. Right now, four banks – United Bank, IOB, Bank of Maharashtra, and Uco Bank – should be considered ripe candidates for narrow banking. The other thing to do is to force these banks to hive off their bad loans into a separate legal entity whose only job will be to retrieve what they can from borrowers. Here’s an idea: in the short run, let the government designate one public sector bank – say Indian Overseas Bank – as a bad bank and sell all the bad loans to it. IOB should focus all its energies on retrieving bad loans and focus only on deposit taking in its newly narrowed down brief. Both these options - narrow banking and hiving off bad loans into “bad banks” - can be done without legislation through regulatory action on the part of the Reserve Bank and support from the finance ministry. Modi and Jaitley have very little room to manoeuvre on public sector banks. It’s time to accept the inevitable and embrace the P-word. The alternative is multiple negative versions of the B word - bankruptcy, bailout and basket cases.

Some PSU banks are dead ducks: Modi has to rethink his aversion to the P-word

R Jagannathan

• August 22, 2015, 13:41:36 IST

Competition is set to intensify for public sector banks, and some of them will be dead ducks unless the Modi government either privatises or downsizes them to become narrow banks

Advertisement

)