Worryingly enough, Narendra Modi continues to draw all the wrong lessons from Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s defeat. There is a counter argument to this statement. Like any other entrepreneurship, political entrepreneurship, too, is governed by the law of returns. Reforms couldn’t save PV Narasimha Rao, neither did Vajpayee return for a second term. If the median of Indian politics continues to shift further to the Left — despite a so-called right-of-Centre government at helm — blame it on the rather disturbing conclusion that instead of wealth creation, welfare and redistribution of wealth bring better political dividends. The end result of this position is that reforms of the kind that we saw during the Vajpayee era — such as on taxation, a separate divestment ministry, privatisation of government’s businesses, freeing businesses of bureaucratic control, progressive trade policies and cooling off of interest rates — have been absent in Modi regime. [caption id=“attachment_6941591” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]

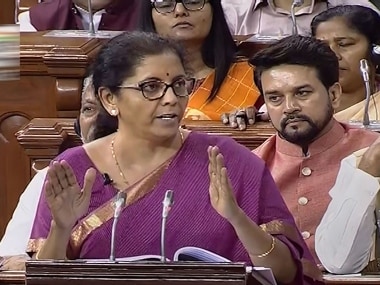

Nirmala Sithraman presenting the budget. PTI[/caption] As we may recall, PSUs such as Bharat Aluminium, CMC, Hindustan Zinc, HTL, Indian Petrochemicals, Modern Food Industries, Paradeep Phosphates, VSNL, Maruti, two hotel units of Hotel Corporation of India Ltd and 17 hotel units of ITDC

were sold to private firms

, while the Supreme Court stopped the government from divesting its stake in oil refiners HPCL and BPCL. In contrast, Modi has strengthened the command-and-control bureaucratic structure and seems to be doubling down on Gandhian socialism as the backbone of economic policymaking. There are, of course, many aspects to this argument. Welfare policies aimed at uplifting the poor cannot be anathema in a country where

per capita income is lower than Congo or Nigeria

. Nobody can argue in favour of reforms without welfare policies and an efficient redistributive mechanism, or else growth may end up fueling more inequality. We must acknowledge three factors where Modi has made a difference. One, there has been a renewed focus on ramping up public spends for welfare schemes so that it may spur higher economic growth. Two, the Modi government has improved significantly upon the last-mile delivery mechanism. Three, policy initiatives such as GST (despite multiple slabs and teething problems) and demonetisation have been successful in increasing compliance and expanding the tax base. It basically means more money in government’s hands. Some commentators have argued that Modi’s stress on social welfare schemes does not necessarily mean that he is a populist. It could be the East Asian model, as Pranab Dhal Samanta points out in The Economic Times

, where “social welfare was seen as a necessary first step towards achieving higher economic growth. These were not rich states like Europe, but they rationalised that without raising social standards they will not be able to create the aspirational conditions necessary to develop a skilled workforce for industrial manufacturing, thus modernisation.” So far, so good. At the same time however, no welfare schemes can be sustained if the economy isn’t registering growth. To register growth and fund the welfare schemes that may kick off a virtuous cycle of the kind we have been in East Asian nations, it is essential that the government makes it easier for companies to start businesses, makes policies that are compatible with expansion of these businesses, make them more competitive in the global arena. Government policies must be focused on encouraging asset creation and there must not be policies that are hostile to entrepreneurs and antithetical to asset creation. This is where, one fear, that the Modi government is losing the plot by focusing too much on socialist policies that choke the arteries of businesses and see asset creation and profit-making as some sort of crime. A case in point is the recent changes in Section 135 of the Companies Act that makes it mandatory for the companies to meet their corporate social responsibility or else face penal action in case of non-compliance. Non-compliance with CSR norms, according to reports, will attract pecuniary penalties for both the company and defaulting officers ranging from Rs 50,000 to Rs 25 lakh. The officers may also be jailed for up to three years as per the provisions in the Companies Amendment Bill, 2019, that received Parliament’s nod on Tuesday. While replying to a debate on Companies (Amendment) Bill, 2019, in the Rajya Sabha, Union finance minister N Sitharaman argued that the amendments that are being brought now are in line with Mahatma Gandhi’s trusteeship principle that holds that profit-making cannot be devoid of social responsibility.

Nirmala Sithraman presenting the budget. PTI[/caption] As we may recall, PSUs such as Bharat Aluminium, CMC, Hindustan Zinc, HTL, Indian Petrochemicals, Modern Food Industries, Paradeep Phosphates, VSNL, Maruti, two hotel units of Hotel Corporation of India Ltd and 17 hotel units of ITDC

were sold to private firms

, while the Supreme Court stopped the government from divesting its stake in oil refiners HPCL and BPCL. In contrast, Modi has strengthened the command-and-control bureaucratic structure and seems to be doubling down on Gandhian socialism as the backbone of economic policymaking. There are, of course, many aspects to this argument. Welfare policies aimed at uplifting the poor cannot be anathema in a country where

per capita income is lower than Congo or Nigeria

. Nobody can argue in favour of reforms without welfare policies and an efficient redistributive mechanism, or else growth may end up fueling more inequality. We must acknowledge three factors where Modi has made a difference. One, there has been a renewed focus on ramping up public spends for welfare schemes so that it may spur higher economic growth. Two, the Modi government has improved significantly upon the last-mile delivery mechanism. Three, policy initiatives such as GST (despite multiple slabs and teething problems) and demonetisation have been successful in increasing compliance and expanding the tax base. It basically means more money in government’s hands. Some commentators have argued that Modi’s stress on social welfare schemes does not necessarily mean that he is a populist. It could be the East Asian model, as Pranab Dhal Samanta points out in The Economic Times

, where “social welfare was seen as a necessary first step towards achieving higher economic growth. These were not rich states like Europe, but they rationalised that without raising social standards they will not be able to create the aspirational conditions necessary to develop a skilled workforce for industrial manufacturing, thus modernisation.” So far, so good. At the same time however, no welfare schemes can be sustained if the economy isn’t registering growth. To register growth and fund the welfare schemes that may kick off a virtuous cycle of the kind we have been in East Asian nations, it is essential that the government makes it easier for companies to start businesses, makes policies that are compatible with expansion of these businesses, make them more competitive in the global arena. Government policies must be focused on encouraging asset creation and there must not be policies that are hostile to entrepreneurs and antithetical to asset creation. This is where, one fear, that the Modi government is losing the plot by focusing too much on socialist policies that choke the arteries of businesses and see asset creation and profit-making as some sort of crime. A case in point is the recent changes in Section 135 of the Companies Act that makes it mandatory for the companies to meet their corporate social responsibility or else face penal action in case of non-compliance. Non-compliance with CSR norms, according to reports, will attract pecuniary penalties for both the company and defaulting officers ranging from Rs 50,000 to Rs 25 lakh. The officers may also be jailed for up to three years as per the provisions in the Companies Amendment Bill, 2019, that received Parliament’s nod on Tuesday. While replying to a debate on Companies (Amendment) Bill, 2019, in the Rajya Sabha, Union finance minister N Sitharaman argued that the amendments that are being brought now are in line with Mahatma Gandhi’s trusteeship principle that holds that profit-making cannot be devoid of social responsibility.

Sitharaman’s attitude, that is reflected in argument that she made during the Rajya Sabha debate, is a worrying sign. Penal provision in case of violation of CSR is a bad idea. The UPA had introduced these norms and it was expected of the NDA government led by Modi, who carried a business-friendly image from his Gujarat chief ministership days, that he will rationalize taxation and do away with these growth-retarding policies. Unfortunately, Modi government seems to be driven by a higher morality of Gandhian principles which leads it to look upon asset creation as a liability. This is a self-defeating posture. It is for the companies to do what they do the best — create assets — and it is the government’s job to put in place a fair taxation policy, welfare schemes and redistributive mechanism that ensures equal distribute of wealth. Doubling down on companies for failing to comply with CSR — which is a form of perverted taxation — is not only unfair, it carries an impression that the government is hostile towards entrepreneurs and the phenomenon of asset-creation itself. Instead of perverted posturing, the government would do well to do away with CSR altogether and convert it into taxes. At least that will fix the inverted paradigm where the companies are asked to what is essentially government’s job — deliver public goods and services — and free the companies to pursue profit and expand their businesses. As it is, India has some of the highest corporate taxation rates that discourages entrepreneurs from expanding their businesses and encourages tax evasion. Adding the CSR burden on companies leave them with very little capital to invest and expand, and that in turn dampen the climate for private investment. While on the one hand the Modi government pitches for private investment to boost growth, on the other hand the finance minister brings in penal provision for non-compliance with CSR that discourages private investment. The government must understand that generating wealth and creating assets is not a crime. Instead it is the best way to pull the population out of poverty. Modi had expressed similar sentiment while addressing a recent seminar of business leaders. One wonders whether he is aware and in control of the growth-retarding policies that his government is belting out, or has he given bureaucrats — who still suffer from a socialist hangover — a free run.

)