In the mid 1950s, Charles Erwin Wilson, who had served as CEO of General Motors, was appointed US Defence Secretary under President Dwight Eisenhower. But during the process of his confirmation by Congressional committees, a controversy broke out because of the blatant conflict-of-interest situation that arose from Wilson’s continuing to hold large holdings of stocks in General Motors.

Wilson was, therefore, pointedly asked if he could ever make a decision as Defence Secretary that would adversely affect the interests of General Motors. Wilson responded to say that he would, but added that he couldn’t possibly conceive of such a situation ever arising because “for years I thought what was god for our country was good for General Motors, and vice versa.“Over time, however, that statement morphed into the more definitive “What’s good for General Motors is good for the country,” and came to represent the wholesale identification of a nation’s destiny with the interests of an industrial group.

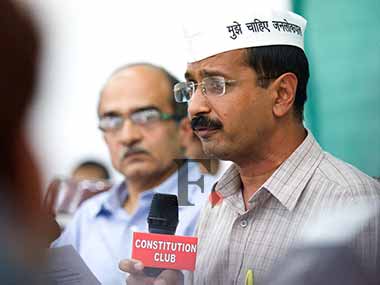

[caption id=“attachment_510037” align=“alignright” width=“380”]

Arvind Kejriwal and Prashant Bhushan want to end ‘business as usual’. Naresh Sharma/Firstpost[/caption]

Arvind Kejriwal and Prashant Bhushan want to end ‘business as usual’. Naresh Sharma/Firstpost[/caption]

In much the same way, for much of the late 1970s and 1980s in India, a period when the early fortunes of the Reliance empire of Dhirubhai Ambani came to be built, the entire edifice of the government - from politicians to bureaucrats - appeared to have internalised the belief that what was good for Reliance was good for India.

In large part, it accounts for how the Reliance empire was built in double-quick time. Dhirubhai Ambani used famously to say that his biggest task was to manage the Indian government, which was “the most important external environment” impacting his business. And because he was a complete newcomer to the business landscape where the Tatas and Birlas were already entrenched players, Ambani had fewer qualms about bending the rules.

What was valorised in the Indian media of the 1980s as a model of dazzling entrepreneurship was, in large part, about bending the arc of government and policy to his advantage. Of Pranab Mukherjee, who served as Finance Minister in Indira Gandhi’s Cabinet in the early 1980s, it was tauntingly asked: “Is he Minister of Finance or Reliance?”

Impact Shorts

More ShortsSo, Arvind Kejriwal’s and Prashant Bhushan’s targeting of Reliance as the master puppeteer that works the levers of the UPA government only carries forward the long-held belief that the Ambanis, even more than other business tycoons, are the real movers and shakers in the government, presiding over ministerial destinies and in turn profiting from the tweaking of policy to their advantage.

In fact, just how much rides on the minutiae of policy - and how deep the political influence of industrial groups runs -was revealed rather more tellingly two years ago, in another of those conversations from the Niira Radia storehouse that made it to the public domain. In that conversation ( details here ), with former bureaucrat and Janata Dal (United) MP NK Singh, Radia reveals that she’s been working overtime to spike news reports that Reliance Industries would reap windfall profits to the tune of Rs 81,000 crore if a tax concession on gas production that the government had announced were to take retrospective effect.

NK Singh in turn briefs her on the elaborate lengths he is going to to ensure that the Opposition - the BJP - doesn’t throw a spanner in the works by creating a ruckus on the windfall profits that would accrue to one company. He frets that Arun Shourie (whom he suspects of working to advance Anil Ambani’s interests at a time when the brothers Ambani were estranged and were at corporate war) would raise the issue, and therefore spoil the party for Reliance Industries. He then peddles his influence to ensure that Shourie is replaced as the BJP’s lead speaker in Parliament by M Venkaiah Naidu.

As Singh reasons: “If (Naidu) is the firsst speaker, and he already takes a party line, then it will be very difficult for Shourie, in his second intervention, to take a different line. Then we have to orchestrate who will speak, you know, this is the immediate problem right now. Because, frankly, if this doesn’t go through, this tax thing, then it’s a major initiative taken that then fails to materialise.”

And, sure enough, in line with Singh’s strategem, Naidu spoke up in defence of tax concessions on the grounds that it enhanced Indi’s “energy security”.

The proposal, however, didn’t go through, because a revenue secretary turned down the proposal to implement the tax concession with retrospective effect, but the episode is illustrative of how well-oiled the machinery of ‘crony capitalism’ is.

Kejriwal and Bhushan may have picked on Reliance as the most proximate target, but their firepower could just as easily have been directed at any other industrial group. So benighted have the fair names of industrial houses become in the wake of recent scandals, and particularly after the Radia tapes exposure of their modus operandi, that even Bollywood lyrics bad-name them in songs that give voice to widespread public anguish about corporates that are reaping unjust riches.

Kejriwal and Bhushan, being newbie politicians, may be making a polemical point and harnessing public outrage. And there may well be inconsistencies in their articulation of how natural resources out to be auctioned, and how they ought to be priced at the end-user level. Butwhat they are effectively signalling is that the old ways ofstriking deals behind closed doors and shifting goalposts to favour one industrial house or another are over.

It is impossible for governments and businesses not to work together, but the results of such interactions will increasingly face demands to meet heightened levels of transparency. Businesses and politicians can carry on with business as usual only at grave risk of having their names tainted in the public imagination. The notion that what’s good for business is good for the country has gone well past its sell-by date.

Venky Vembu attained his first Fifteen Minutes of Fame in 1984, on the threshold of his career, when paparazzi pictures of him with Maneka Gandhi were splashed in the world media under the mischievous tag ‘International Affairs’. But that’s a story he’s saving up for his memoirs… Over 25 years, Venky worked in The Indian Express, Frontline newsmagazine, Outlook Money and DNA, before joining FirstPost ahead of its launch. Additionally, he has been published, at various times, in, among other publications, The Times of India, Hindustan Times, Outlook, and Outlook Traveller.

)