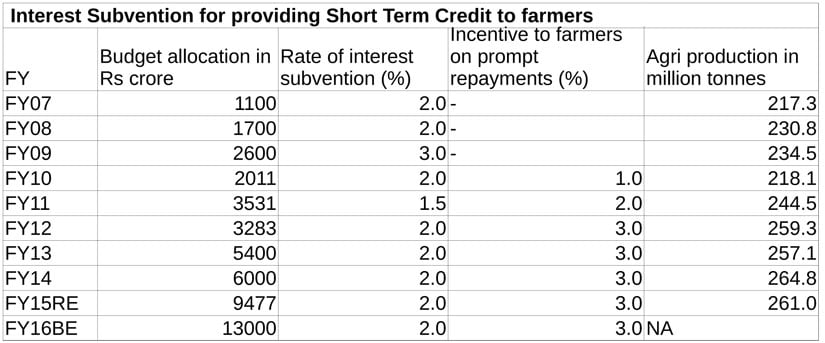

On Tuesday, the union cabinet approved the extension of the interest rate subvention on farm loans for 2015-16. A practice that is religiously followed every year, the scheme offers short-term crop loans to small and marginal farmers at 7 percent. The government compensates banks for 2 percent interest. For the current year, the target is to disburse Rs 3 lakh crore under the scheme. On proper repayment, the interest rate further falls by another 3 percent, taking the final rate of interest for the borrower at about 4 percent. As a point of comparison, small-sized industries looking for bank loans, get money at almost double rate (of 13-14 per cent). [caption id=“attachment_2356522” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  AFP[/caption] The question here is does the farm sector deserve to be subsidised so heavily at the cost of industries? Probably, it is time the government did a re-look at the actual impact of subsidised money on the country’s farm output and to what extent such mechanisms have contributed to the income generation of small farmer. This needs to be seen against the backdrop of small industries still struggling to get funding at reasonable rates. Contribution of the farm sector to the gross domestic product (GDP) has been declining steadily over years, now about 15-16 percent, while the share of micro, small and medium-sized firms has shown promising growth. Various estimates put the share of Indian SMEs to GDP at 22 percent and that of MSMEs at about 20 percent in the next five years. A look at the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) data shows farm loan outstanding of Indian banks is currently around Rs 8 lakh crore and is targeted to increase to Rs 8.5 lakh crore this year. A major chunk of the money lent to agriculture is disbursed through Kisan Credit Cards (KCC). A member of the RBI’s central board, on condition of anonymity, told this author that the repayment on money disbursed through KCC has been poor while use of the funds for consumption-related activities has grown in size. Moreover, the guaranteed availability of cheap money has given rise to wrong practices among the beneficiaries. Farmers often divert the money borrowed from banks for other consumption related purposes. The RBI has woken up to this problem and has begun a probe on the actual disbursement of the money to assess the risk in the sector.  Besides pure agriculture loans, loans given against gold, is also categorised as farm loans in many parts of the country. As the report notes, there have been instances of farmers diverting the cheap farm/ gold loans (availed at 4 percent) to fixed deposits and deploy tractors, originally bought from farming, in construction works. The RBI has further noted that the repayment ability of the small, landless farmer to banks is poor given the lower income levels and high share of consumption spending. Recently, quoting the 70th round of NSSO survey, RBI deputy governor H R Khan had said that an average farmer earns Rs 6,400 a month. “If we take out his expense and consumption needs, he is left with a surplus of a paltry Rs 200 a month. So, how is he going to service a loan, which is an average of 4,700 a month?” Khan asked. The short message here is that the small farmer is getting more indebted to the banking system, while his income levels have hardly grown enough to support his family and pay his bills. The government clearly needs to think why the average income of farmers and the farm output have not grown despite pumping in highly subsidized money year after year. Clearly, something is amiss beyond the funding aspect. The problem might be lying with small land parcels used by average farmer, archaic methods of cultivation, high dependence on monsoon for irrigation and large-scale diversion of funds to consumption-oriented purposes, not crop production. As Firstpost has noted before blindly forcing banks push cheap money to farm sector to appease the vote bank, has worsened the risk in the banking system. For a government dealing with the puzzle of how to save the weak state-run banks, it makes immense sense to rethink on the subvention scheme for farmers. Farm loans are a big stress area for banks, especially state-run ones. Perhaps, instead of subsidising interest rates, the money can be directly invested in developing the agriculture infrastructure or improve the distribution mechanism. The government shouldn’t be blind to the woes of industries since the next leg of growth should come from that segment. Small industries have been struggling to get money to fund their growth. Credit growth to industries has slowed to a trickle in the recent years and hasn’t picked up yet partly due to slow demand and partly on account of high bad loans on the balance sheets of banks. For the 12 months ending March, bank lending to MSMEs grew at 5 percent compared with 11 percent in the year-ago period. In the first two months of 2015-16, the loan book has actually shrunk. The government, which is targeting double-digit GDP growth rates in the foreseeable future, must prioritise resource allocation. India’s farm economy is broke beyond repair, but still half of the countries population is employed in the sector. The focus should be to increase the efficiency of farming and increase production. The latest estimates show that even as an income generator, agriculture has lost its shine for rural households to manufacturing and service sectors. The bottomline is the current funding structure of India’s ailing agriculture sector is flawed primarily due to absence of mechanism to monitor the end-use of the money. Where the subsidised funds disappear every year without a trace (they don’t show on the income or agriculture production) remains as a big question mark. Data inputs from Kishor Kadam

The bottomline is the current funding structure of India’s ailing agriculture sector is flawed primarily due to absence of mechanism to monitor the end-use of the money

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)