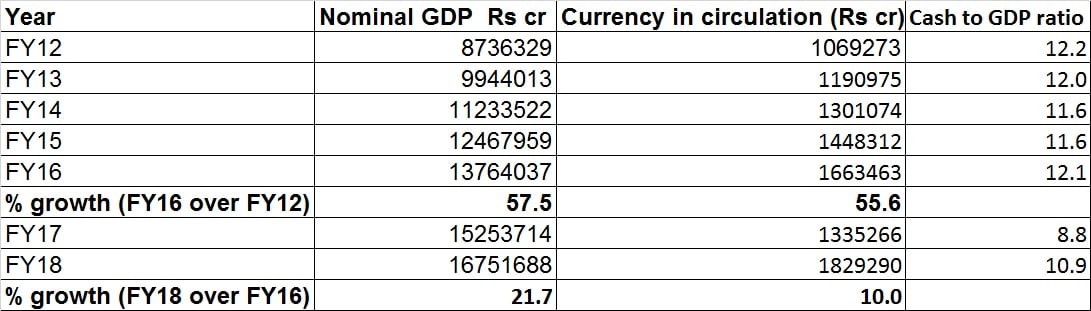

Multiple theories are doing the rounds about the reasons for the ongoing cash crunch that caught both the government and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) off-guard, forcing them to admit that the shortage is no made-up story. The theories point to large scale hoarding of Rs 2,000 notes, uneven distribution of currency notes moved to currency chests in different states, and to the work of hawala operators. [caption id=“attachment_4342295” align=“alignleft” width=“380”] ATM. Representational image. Reuters.[/caption] At least three senior bankers, including two former chiefs of the State Bank of India (SBI), and a few economists with large private institutions, told this writer that all of these reasons could have contributed to the current mess, but the biggest reason is that the growth in currency in circulation (CIC) in the economy doesn’t match the pace of GDP growth. To begin with, the currency shortage didn’t pop up overnight. The system was largely running short of cash since the note-ban, announced in November, 2016. To understand this mess, it is important to look at the trend in currency in circulation (CIC), an important metric to assess cash situation. It tells us that post demonetisation, the growth in CIC has not kept up with the growth in nominal GDP. The system is painfully short of cash and a State Bank of India (SBI) Research report pegged the shortage at Rs 75,000 crore. In reality, that shortage is much larger. The math To understand this, let’s look at the average growth in CIC for the last 10 years, which figures at around 14 percent. Just before demonetisation, as on 4 November, 2016, CIC was Rs 17.98 trillion. Suppose demonetisation never happened, and had the CIC grown at an average rate of 14 percent, the CIC in November 2017 would have been Rs 20.5 trillion. However, in November 2017, this figure stood at only Rs 16.5 trillion. This means, the system was short of almost Rs 4 trillion. Now, the abovementioned numbers need to be seen in conjunction with the cash-to-GDP ratio. India is a cash-intensive economy that comprises of a huge informal sector (which employs 70-80 percent of its people). The sudden withdrawal of 86 percent of all cash, during demonetisation, dealt a bloody blow to the informal segment. Since then, the point to note here is that cash-to-GDP ratio has shrunk substantially despite the CIC growing to Rs 18.3 trillion in FY18, or around 10.9 percent of GDP as compared with 12-13 percent of GDP prior to demonetisation. In FY17, it was 8.8 percent, while in FY16 it was 12.1 percent. Now, if one compares the growth in CIC and the growth in nominal GDP for the last six years, it is quite evident that post demonetisation, the CIC failed to catch-up with the pace in GDP growth by a significant margin. Between FY12 and FY16 (prior to demonetisation) the growth in CIC was 55.6 percent while the growth in the nominal GDP rate was 57.5 percent. But, in the two-years post demonetisation, the growth in CIC was a meagre 10 percent while nominal GDP grew at 21.7 percent. (see below table)

Clearly, killing cash in India wasn’t a good idea as reflected in the decline in growth figures and demand slowdown. The fall in the cash-to-GDP ratio mainly happened due to a forced change to non-cash methods and the fact that not enough cash was printed post demonetisation, to bridge the gap in a growing economy. What the RBI and the government focused on was printing of Rs 2,000 notes. These reflected in a higher value of the total currency in circulation but lower units to go around. It was easy to hoard the new pink notes and presumably politicians and cash hoarders stashed away a large number of Rs 2,000 notes. This sharply increased the demand for the next high denomination, the Rs 500 note. There aren’t many countries where currency denominations have been managed as badly as India did post-demonetisation. The issuance of the Rs 2,000 note post demonetisation went against the idea of nudging the economy to a cashless society. The government and the RBI miserably failed to understand the simple fact that people needed more lower denomination currencies to transact, and not the ‘hard-to-break’ Rs 2,000 notes. The utopian idea of changing India to a digital, non-cash society worked to an extent, in the case of large institutional transactions (by forcing companies to deal in non-cash) but not with the layman as reflected in retail electronic payment data. Digital transactions picked up significantly in the weeks that followed the demonetisation announcement mainly because there was no cash available. But that pace has slowed down. The growth has been mainly on large institutional transactions but not on retail transactions. Even though the usage of instruments such as the UPI has gone up, the quantum is not substantial. Then came reports that the RBI stopped printing or circulating Rs 2,000 notes, apparently a few months back, as part of a plan to gradually withdraw the hard-to-break pink notes. This worsened the situation as there weren’t any Rs 1,000 notes to bridge the gap. Also, cash hoarders loved the Rs 2,000 bills. Amid regional elections and ahead of general elections in 2019, it isn’t illogical to imagine that political parties are busy hoarding cash to fuel their election machines. But all these happened later. To sum up, the Indian economy doesn’t have adequate CIC in tandem with economic growth ration and demand. Demonetisation induced a severe cash crunch, from which the system has not recovered yet. The pace of the CIC growth was disturbed. When the cash-to-GDP ratio dropped sharply, digital transactions didn’t play a supporting role to the extent needed. Adding to the crisis, the RBI might have stopped printing and circulating Rs 2,000 notes. Cash hoarders played their part, triggering a full blown cash crisis. The Modi government and the RBI together built a self-made currency crisis in India beginning with the destructive demonetisation exercise. In hindsight, it is fair to say that India wouldn’t have faced a cash shortage like the one impacting daily life these days if the demonetisation-induced cash crunch hadn’t dealt a blow to the economy. (Data support from Kishor Kadam)

Clearly, killing cash in India wasn’t a good idea as reflected in the decline in growth figures and demand slowdown. The fall in the cash-to-GDP ratio mainly happened due to a forced change to non-cash methods and the fact that not enough cash was printed post demonetisation, to bridge the gap in a growing economy. What the RBI and the government focused on was printing of Rs 2,000 notes. These reflected in a higher value of the total currency in circulation but lower units to go around. It was easy to hoard the new pink notes and presumably politicians and cash hoarders stashed away a large number of Rs 2,000 notes. This sharply increased the demand for the next high denomination, the Rs 500 note. There aren’t many countries where currency denominations have been managed as badly as India did post-demonetisation. The issuance of the Rs 2,000 note post demonetisation went against the idea of nudging the economy to a cashless society. The government and the RBI miserably failed to understand the simple fact that people needed more lower denomination currencies to transact, and not the ‘hard-to-break’ Rs 2,000 notes. The utopian idea of changing India to a digital, non-cash society worked to an extent, in the case of large institutional transactions (by forcing companies to deal in non-cash) but not with the layman as reflected in retail electronic payment data. Digital transactions picked up significantly in the weeks that followed the demonetisation announcement mainly because there was no cash available. But that pace has slowed down. The growth has been mainly on large institutional transactions but not on retail transactions. Even though the usage of instruments such as the UPI has gone up, the quantum is not substantial. Then came reports that the RBI stopped printing or circulating Rs 2,000 notes, apparently a few months back, as part of a plan to gradually withdraw the hard-to-break pink notes. This worsened the situation as there weren’t any Rs 1,000 notes to bridge the gap. Also, cash hoarders loved the Rs 2,000 bills. Amid regional elections and ahead of general elections in 2019, it isn’t illogical to imagine that political parties are busy hoarding cash to fuel their election machines. But all these happened later. To sum up, the Indian economy doesn’t have adequate CIC in tandem with economic growth ration and demand. Demonetisation induced a severe cash crunch, from which the system has not recovered yet. The pace of the CIC growth was disturbed. When the cash-to-GDP ratio dropped sharply, digital transactions didn’t play a supporting role to the extent needed. Adding to the crisis, the RBI might have stopped printing and circulating Rs 2,000 notes. Cash hoarders played their part, triggering a full blown cash crisis. The Modi government and the RBI together built a self-made currency crisis in India beginning with the destructive demonetisation exercise. In hindsight, it is fair to say that India wouldn’t have faced a cash shortage like the one impacting daily life these days if the demonetisation-induced cash crunch hadn’t dealt a blow to the economy. (Data support from Kishor Kadam)

Post demonetisation, the growth in currency in circulation has not kept up with the growth in India’s nominal GDP.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)