In 28 February 1997, Palaniappan Chidambaram presented what was called a Dream Budget perhaps the only effort by a finance minister in independent India to be extolled to the skies.

It was a path-breaking reforms budget which cut taxes (corporate, personal and dividend), promised fiscal rectitude, disinvestment and public sector autonomy, offered swashbuckling capital market reforms, reduced peak customs duties, and revamped the excise structure to three basic slabs. These were the reforms that delivered growth in subsequent years, and particularly over the last decade.

If Manmohan Singh’s 1991 reforms freed the economy, Chidambaram provided the mid-course energisers.

And remember, his was a United Front coalition government where the Left was actually inside the ministry. Chidambaram still pulled it off - the budget at least.

It was a disaster. In less than a year, the Dream Budget produced a nightmare scenario of falling growth, with GDP growth almost halving from 8 percent in 1996-97 to 4.3 percent in 1997-98.

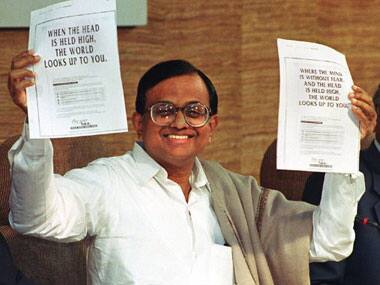

[caption id=“attachment_207913” align=“alignleft” width=“380” caption=“In less than a year, the Dream Budget produced a nightmare scenario of falling growth, with GDP growth almost halving from 8 percent in 1996-97 to 4.3 percent in 1997-98. AFP”]

[/caption]

[/caption]

Looking back, it seems as if Chidambaram must have got everything wrong - and the budget must offer lessons on what not to do.

Well, sure.

But the reason why the dream soured had nothing to do with what the budget contained. It had the right ideas, but the timing was wrong. Chidambaram’s luck went phut. After two years of robust growth in the economy (7.3 percent in 1995-96 and 8 percent in 1996-97), Chidambaram was staring into a cyclical downturn with agriculture and industry both set to disappoint in 1997-98. Commercial interest rates were still a usurious 14-15 percent, just starting to ease up after C Rangarajan had put them up viciously after Manmohan Singh’s fiscal overspend (ditto now).

As his successor as FM, Yashwant Sinha of the BJP, noted the following year: “In my interim budget speech I had already drawn attention to some disquieting trends: overall economic growth slowed to 5 percent in 1997-98; agricultural growth was negative, with foodgrain production dropping to194 million tonnes from199 million tonnes in the previous year; growth of industrial production slackened to 4.2 percent; export performance was weak for a second successive year, recording growth in dollar terms of less than 3 percent; the fiscal deficit worsened to 6.1 percent of GDP; the capital market remained in the doldrums and infrastructure bottlenecks continued to plague the economy. But I am not daunted by the situation. Only the weak are tamed by adversity, the strong rise above them.”

It is a moot point if Sinha really rose above his adversity, but the fact is Chidambaram’s reforms started delivering the goods the year after the economy went into a tailspin. In 1998-99 and 1999-00, growth rebounded to 6.7 percent and 6.4 percent respectively, thanks in part to Chidambaram’s efforts. The dotcom boom and bust followed, but when global liquidity conditions improved under George W Bush in the early 2000s, the Indian economy took off. Chidambaram, Sinha and Jaswant Sinha are the people to thank.

On 16 March this year, when Finance Minister Pranab Mukherjee will present his fourth budget under the UPA dispensation, it could be time to risk another Dream Budget. While the economic situation is troublesome - and hence he could borrow from Manmohan Singh’s 1991 budget speech as well (see here) - India is not the economic weakling it was 20 years ago. So the right mix is the Singh austerity combined with Chidambaram’s Dream Budget audacity (Read the Dream Budget Speech here ).

Hopefully, it could lead to better results a year or two down the line.

Like 1997-98, agriculture will remain an unknown till we actually see what happens with the monsoon this year. But industry could begin to bounce back, given the likely fall in interest rates over the coming months, and the return of some optimism in the capital markets. As the third quarter results showed, corporate profitability is still holding up, and if capital inflows retain their buoyancy, 2012-13 will mark a bottoming out of the economy, setting the pace for a robust revival in 2013-14 - just in time for the next general elections.

In short, we need a Dream Budget in 2012-13 not because it will stoke growth this year itself, but because it will work the year after that.

In 2012-13, thanks to high inflation, still high interest rates, a slowdown in capital spending, and fiscal profligacy due to excess social sector spending, the budget has to be long on supply side reforms and fiscal consolidation, and aggressive in cutting non-merit subsidies - especially oil and power.

The following are some of the key ideas Pranab-da can borrow from Chidambaram’s Dream Budget. The text in italics is from Chidambaram’s 1997 original. The text in bold is our addendum.

Chidambaram said then: Drawing on the CMP (Common Minimum Programme), my first budget articulated seven broad objectives. These objectives embraced vital elements such as growth, basic minimum services, employment, macroeconomic stability, investment (particularly in infrastructure), human development and a viable balance of payments. I believe these objectives remain as valid today as they were eight months ago. We agree.

The one commitment that I have been unable to keep is to set up an Expenditure Management and Reforms Commission. I failed because I wanted an A team and I was not content with a B team. Key members of the A team are in this House and in the Rajya Sabha, and they still elude me. I shall keep trying. Meanwhile, I have not let up on my resolve to keep expenditure within the budget, and I have achieved a fair measure of success. Pranab’s challenges are to rein in unproductive spending. He needs an A-Team, too.

Two areas of great concern are the sharp drop in domestic crude oil production and the sluggish performance of the power sector. Other matters of concern include a deceleration in the growth of exports, a rise in the rate of inflation and a volatile capital market. Government has addressed these concerns through some far-reaching initiatives in the last three months. I have also fresh proposals in this budget. Ditto this year for Pranab. He needs to address these concerns through “far-reaching reforms” of his own.

Macroeconomic management involves, inevitably, striking a balance between various objectives and considerations. As Hon’ble Members are aware, in 1995-96, the growth in money supply was reduced sharply to 13.2 percent. Although this helped to contain inflation, it also led to high real interest rates, a widespread perception of a liquidity crunch and a slackening of investment proposals. Since June 1996, corrective action has been taken which has eased the availability of money and brought down the interest rates. The long-delayed increase in the prices of petroleum products and supply side problems, arising mainly out of lower production and lower procurement of wheat in the last season, exerted pressure on the price level. The only difference this time is that prices are rising for the opposite reason: high procurement prices and high pre-emption of supplies from the market to feed the Food Security Bill, apart from supply side issues in protein-based items like pulses, fruits, eggs, and milk. Energy prices need to be hiked to cut subsidies and enable fiscal consolidation.

Continues on the next page

Maintaining price stability is high on the agenda of this government. Apart from supply side management, we have to adopt prudent fiscal and monetary policies that will stabilise prices. For the year 1997-98, government and the RBI will act in concert towards a further reduction in the fiscal deficit, containment of the growth of money supply within 16 percent and adoption of a liberal import policy for essential commodities. Our goal is to break inflationary expectations and reduce the rate of inflation from the present level. Ditto for Pranab, barring the dates and updated money supply figures.

The CMP said that all controls on agricultural products will be reviewed and, wherever found unnecessary, will be abolished. Only some regulations are by the Central government, and a beginning is being made by abolishing a few. The Rice Milling Industries (Regulation) Act, 1958, and the Ginning and Pressing Factories Act, 1925, will be repealed. Licensing, price control and requisitioning under the Cold Storage Order, 1964, will removed. The Edible Oils and Edible Oil Seeds Storage Control Order, 1977, and the Cotton Control Order, 1986 will be invoked only in well-defined emergency situations. Domestic futures trading would be resumed in respect of ginned and baled cotton, baled raw jute and jute goods. An international Castor Oil Futures Exchange will be set up. I urge State governments to follow this lead and abolish as many controls as possible. The states have not abolished the restrictive agricultural produce marketing committees, or removed all inter-state barriers to agricultural trade. If this is done, we will have one national market for agri-produce, bringing in efficiencies all across the supply chain.

[caption id=“attachment_207938” align=“alignright” width=“380” caption=“AFP”]

[/caption]

[/caption]

The CMP promised that “the United Front government will identify public sector companies that have comparative advantages and will support them in their drive to become global giants.” To begin with, nine well-performing public sector enterprises, the Navaratnas, have been identified. These are IOC, ONGC, HPCL, BPCL, IPCL, VSNL, BHEL, SAIL and NTPC. The Industry Minister will shortly unveil a package of measures that will help them achieve this objective. He will also make a full statement on managerial and commercial autonomy to all PSUs.In the meanwhile, government has decided to delegate more monetary powers to the boards of profit-making enterprises. Three of the oil companies mentioned by Chidambaram in 1997 and Air India and the two public sector telecom companies are basket cases today because of UPA policies and ministerial meddling. If all public sector units are removed from the administrative control of various ministries, we will see a marked improvement in their performance and contributions to the exchequer. This is Pranab’s prime job, even before disinvestment.

The country’s demand for petroleum products is growing at over 8 percent per annum, which is faster than the growth of domestic supply. We cannot choke this growth. At the same time, we must reduce our dependence on imported petroleum products. There is no real alternative to increasing the supply. Just 6 of the 26 basins that have potential for oil and gas in India have been explored, and that too only partially. The Minister of State for Petroleum and Natural Gas will be making a detailed statement on the new exploration licensing policy (NELP) shortly. The highlights of the policy (include) the following: Companies, including ONGC and OIL, will be paid the international price of oil for new discoveries made under the NELP; Freedom for marketing crude oil and gas in the domestic market. This promise of Chidambaram in 1997 remained a dead letter and needs to be honoured in 2012. The UPA, on the other hand, has moved in the opposite direction and reduced even petrol deregulation to a caricature.

I am of the firm view that markets will prosper when economic growth continues to be strong, the fiscal deficit is reduced, interest rates decline and investors are reassured that their interests are secure. Hear, hear.

Several countries have used a variety of indexed bonds to provide investors an effective hedge against inflation and to enhance the credibility of anti-inflationary policies followed by the government. I believe the time is ripe for India to introduce such an instrument. I, therefore, propose to introduce a capital indexed bond where the repayment of the principal amounts will be indexed to inflation. Inflation-indexed bonds are the need of the hour in 2012.

In the rest of his speech, Chidambaram proposed tax cuts of various kinds, completing the dream budget picture. What Pranab can do this year is a bit of the opposite - extend service taxes to more areas - but avoid raising excise rates just to generate revenue. By retaining the stimulus, and giving special concessions for investments, he can get the economy moving again in a year.

Chidambaram concluded his speech thus, quoting China’s reformer Deng Xiao Peng: “From our experience of these last few years, it is entirely possible for economic development to reach a new stage every few years. Development is the only hard truth.” India’s economy has also reached a new stage. Our beloved India is far stronger today than she was six years ago_._

Pranab, of course, can’t say this. While the underlying economy is strong, the growth impulses have been destroyed by fiscal debauchery. Which is why the remedy for Mukherjee is a mix of Manmohan Singh 1991 austerity and Chidambaram’s Dream which will deliver some energy price deregulation, some fiscal consolidation, sops for investment and moderate tax relief.

It just could work.

)