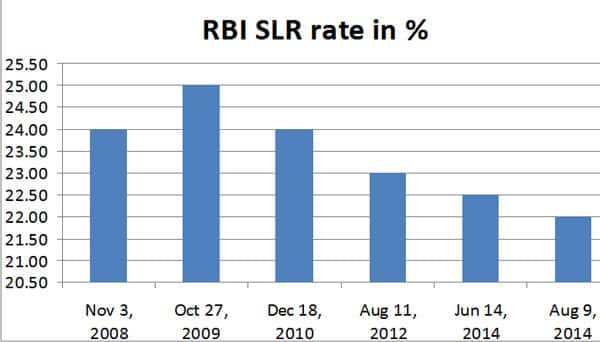

When RBI governor Raghuram Rajan announced yet another half percentage point reduction in the statutory liquidity ratio (SLR) of banks to 22 percent, the former international monetary fund chief economist has taken the ratio, which requires banks to mandatorily fund the government’s borrowing by investing in government bonds, back closer to the levels in March 1949.

In other words, SLR is now at almost the lowest level since India’s independence. The most important point to be noted here: By gradually phasing out SLR, the Indian central bank is taking Indian economy out of the so-called financial repression. After Rajan took over in September, 2013, the SLR has been reduced twice by a total of one percent.

Financial repression, in economic parlance, is a form of directed lending employed by governments using central banks to channelise funds from commercial banks of a country to themselves and denying fund flow to the private sector. A higher SLR holding means banks are forced to fund a higher chunk of government borrowing.

The term financial repression was originally introduced in 1973 by Stanford economists Edward S Shaw and Ronald I McKinnon. This can be implemented directed lending to the government, caps on interest rates and regulation of capital movement between countries. The term was initially used in response to the emerging market financial systems during the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s.

Financial repression has huge adverse impact on the private sector because banks have to mandatorily invest in SLR securities upon which they earn a lower interest than had they been able to use the funds to give away loans. Reducing SLR requirement means banks can use the money they previously invested in SLR for lending to the private sector. In other words, lower SLR would mean that banks need to make lesser reserves on their incremental deposits.

SLR stood at 20 percent in March, 1949 and was increased to 25 percent in September, 1964. Since then the ratio has only gone up for long. It touched a peak of 38.50 percent in September, 1990. Since then the ratio has come down.

After the policy announcement, the benchmark BSE Sensex fell as much as 257 points or one percent. The rupee and bond prices too fell. The reason was that the markets interpreted the SLR cut as a non-event - something that will not have any immediate positive impact on banks. That is true, in the short-term. The current SLR holding of banks, on an average, is about 28-29 percent. This would mean that except those banks, which are on the brink of minimum SLR holding, the cut doesn’t really make any sense to anyone.

That is so especially in a scenario, when the credit demand remains sluggish and bad loans are at high. Rather risking their money, banks would rather prefer to park their money in government bonds and stay tension-free. Also, Indian companies are still struggling to lift their stuck projects due to the combined impact of a slowing economy and various clearance bottlenecks at central and state levels.

Even though the Narendra Modi government has promised to breathe life into the sagging economy and cure the policy paralysis, it will still take at least a few quarters before the changes take effect on the ground. But the notable point is when the revival finally takes effect, the excess cash on the books of banks on account of freeing of SLR, will come handy. In that sense, the decision to cut SLR is a smart move.

Rajan has also taken comfort from the government’s promise to cut the borrowing by putting in place a fiscal consolidation roadmap. Jaitley has promised to check the fiscal deficit at 4.1 percent.

Total borrowing for the fiscal year 2014-15 is scheduled at Rs 6 lakh crore and the net borrowings minus redemptions, at around Rs 4.61 lakh crore. Until 1 August, the government has borrowed Rs 2.64 lakh crore.

(Kishor Kadam also contributed to this article)

)