The government’s policy of redistribution is clearly not working.

As Firstbiz has argued earlier , the UPA’s populist scheme like NREGA (which guarantees 100 days of employment to poor households in rural areas)are causing a structural shift in income consumption pattern, have distorted the labor market , and artificially jacked up both the cost of labor and inputs**.**

So why does does the government even pretend tofight inflation when it is engaging in schemes that raise prices across the board?

We know that the UPA’s growth problem is largely the result of a high fiscal deficit and the government’s insistence on pushing high rural wage growth.

But they, Morgan Stanley points out, lead us to an even bigger problem: The UPA’s preference for income redistribution over income growth has generated the side effects of weaker economic growth and slower job creation,according to Chetan Ahya of Morgan Stanley. Ahya maintains that this has further eroded the purchasing power of households and likely to have increased income inequality.

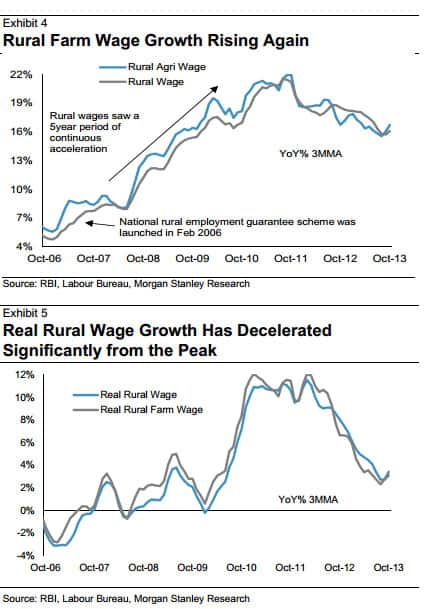

[caption id=“attachment_80157” align=“aligncenter” width=“425”]

Source: Morgan Stanley[/caption]

Source: Morgan Stanley[/caption]

In the chart above, it can be seen that asimplementation of the government’s National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) scheme picked up in 2009, rural wages rose above nominal agricultural output growth.

One f the key criticisms against such schemes that it has pushed up the wage inflation and reduced supply of labour in the rural job market. The scheme has also failed in creating productive assets, which was its stated aim.

Many have attributed the rise in rural wages to increased demand in construction, but Morgan Stanley notes that it “is hard to believe that the demand for construction jobs had picked up right when construction as well as industrial production growth have been decelerating.”

Although the amount allocated to NREGA has been declining as a percentage of GDP, Morgan Stanley believes that this scheme’s wage effect has been underestimated.

“We believe generalized wage pressures for 70 percent of the workforce (from NREGA or any other factors) at a time of deceleration in investment, economic growth and new jobs growth is one of the key factors behind the recent stagflation-type environment.”

Stagflation is a difficult economic situation, characterised by high inflation and stagnating economic growth.

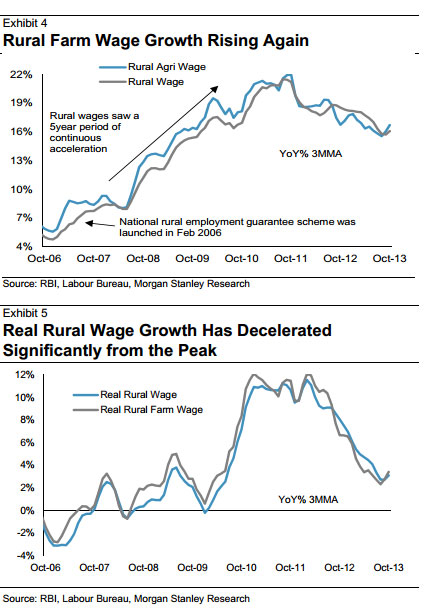

As a result of high inflation, therural population, which has beenthe focus of the redistribution efforts, is no longer reaping the benefits of higher nominal rural wage growth. “Higher rates ofrural inflation have meant that real rural wage growth has now decelerated to 3.4% from a peak of 12.3%. Hence, the redistribution policies seem to have left the country with a sub-optimal outcome in the goal of maximizing economicwelfare,” said Ahya.

In order to address this stagflation-type environment, the new government will have to implement measures such as ensuring a national-level strict audit process, such that the NREGA scheme engages the rural population to build productive assets.

“A process whereby outlays are linked to a strict audit mechanism could also help to improve efficiency and reduce the scheme’s negative externality,” noted Morgan Stanley.

Earlier this year, Business Standard had reported that the BJP plans onredesigning welfare schemes like MNREGA in such a way that these “raise productivity and lead to asset creation.”

The scheme will be be restructured and modelled on the Pradhan Mantri Grameen Sadak Yojana (PMGSY), a scheme introduced by the National Democratic Alliance government in 2000, which was aimed at constructing roads to connect the remote rural areas in the country, according to the newspaper report.

)