Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen is now raising a stink over toilets.

In an interview to The Guardian newspaper, coinciding with the publication of his latest book, An Uncertain Glory, co-authored with Jean Dreze, he expresses outrage over the fact that half of India’s population does not have access to latrines. He had talked about this earlier this year too .

[caption id=“attachment_974889” align=“alignleft” width=“380”] Reuters[/caption]

Reuters[/caption]

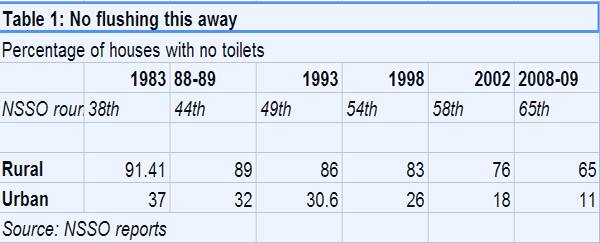

Sure, the eminent economist has a point, which no Indian can refute. The National Sample Survey’s (NSS) report from its 65th round, Housing Conditions and Amenities in India, 2008-09, shows that 49.2 percent of all Indian households had no latrine at all (these are the last available figures). The situation was worse for the rural areas - 65.2 percent (it was 11 percent for urban households). The baseline survey of gram panchayats undertaken as part of the Total Sanitation Campaign shows that as of 2012, 55.63 percent of rural households don’t have a toilet. Open defecation is a blot on any civilised society and India needs to be ashamed of its record in this matter. Especially when, as Sen says, in tiny Bangladesh only 8 percent of houses lack toilets.

But what doesn’t pass the smell test is Sen using this as yet another stick to beat the post-1991 economic liberalisation process (which is the running theme of the book). “This is India’s defective development,” he asserts to the Guardian.

Defective development? Really?

And then Sen resorts to his standard ploy of conjuring up evocative images to make emotional points, never mind their factual accuracy or inaccuracy. “In Delhi when you build a new condominium there are lots of planning requirements but none relating to the servants having toilets. It’s a combination of class, caste and gender discrimination.”

In the mid-1990s, when India’s buffer stocks of food soared, even as starvation deaths were being recorded in Odisha, he spoke about bags of foodgrains going all the way up to the moon and back several times. Earlier, this year, he lambasted the Opposition for stalling Parliament, asserting that delays in the passage of the National Food Security Bill would be responsible for deaths of millions of under-nourished children.

All this makes for great tear-jerking copy but the problem with such glib - and vague - generalisations is that you can never conclusively prove them right or wrong. For every condominium that Sen talks about without servants’ toilets, there will be another which does provide for public toilets.

So let’s junk emotions and get into the realm of hard facts, based on NSS surveys on housing conditions. Were things better before 1991, when governments were not fixated on growth and supposedly did a lot of developmental spending?

[caption id=“attachment_974907” align=“aligncenter” width=“600”] Table 1[/caption]

Table 1[/caption]

In 1983, 91.4 percent of rural households had no latrines. In 1993, the figure stood at 89 percent - a decline (and so an improvement in terms of sanitation) of just 2 percentage points. This was in spite of a Central Rural Sanitation Programme (CRSP) being launched in 1986. The corresponding figure for urban households was 36 percent in 1983 and 32 percent in 1993 - a decline of just 4 percentage points respectively.

The riposte that this will immediately attract is that Sen has not said things were better before 1991, but just that the growth-obsessed development model post 1991 has failed to address the problem.

The figures don’t bear that out as well.

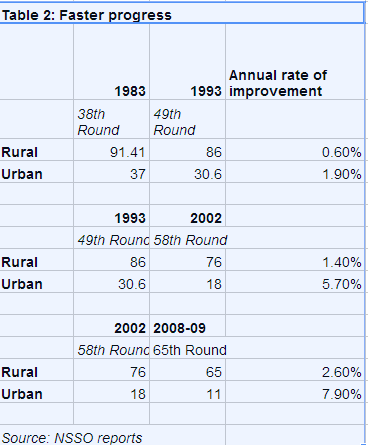

Not only has there been a steady decline in the number of households with no latrines from 1983, but the pace of decline/improvement has been faster after 1993. Between 1983 and 1993, the annual rate of improvement in rural households was less than 1 percent a year and that of urban households a shade short of 2 percent. But between 1993 and 2002, the improvement was 1.4 per cent and 5.7 percent a year respectively (see table 2 below)

[caption id=“attachment_974869” align=“alignleft” width=“368”] Table 2[/caption]

Table 2[/caption]

Statistical purists would be right in pointing out that the second period of nine years will show better results than the first period of 10 years, but the difference is significant enough not to be affected by just one year. And even if one does a simple arithmetic calculation on the decline in households with no toilets between various rounds, the difference is larger between the post-1993 rounds than in the pre-1993 ones.

Here’s another little-known fact. An improved version of the CRSP - the Total Sanitation Campaign (TSC) - was launched in 1999. TSC is a demand-driven programme, focusing on generating awareness among people and getting them to take the initiative for installing latrines. This approach was adopted, according to a June 2010 document setting out guidelines for TSC, after a survey in 1996-97 found that 55 percent of those with private toilets were self-motivated and only 2 percent were influenced by the availability of subsidy. Demand for better living standards comes with rising aspirations and rising aspirations come with higher economic growth, something India’s socialist policies did not ensure.

Yes, the improvement is faster in urban areas than in rural areas (but that is the case of all infrastructure). And yes, the number of rural households without toilets is still unacceptably high. The TSC’s stated aim of ending the practice of open defecation by 2017 does seem a bit unrealistic at this point. But sanitation is not a policy black hole Sen would like us to believe. Yes, the fact that half the population defecates in the open does dent the growth narrative - and could also harm it in the long run because of ill-health and malnutrition. But does that make India’s development `defective'?

Unfortunately, such airy dismissal of the Indian growth story is part of the ceaseless campaign against the directional shift in economic management that India took in 1991. Facts are ignored or distorted when they can’t be ignored.

So first, we were told that poverty has increased post-1991. When figures showed - and conclusively at that - that poverty was declining, questions were raised about the methodology. When that was addressed, and it was demonstrated that whatever the methodology used poverty had fallen, social indicators cited selectively - very selectively - to mock at whatever progress has been made.

India may not exactly be shining, but it is not as tarnished as Sen and his bandwagon would have us believe. The facts and figures can’t be flushed away easily.

(Seetha is a senior journalist and author)

)