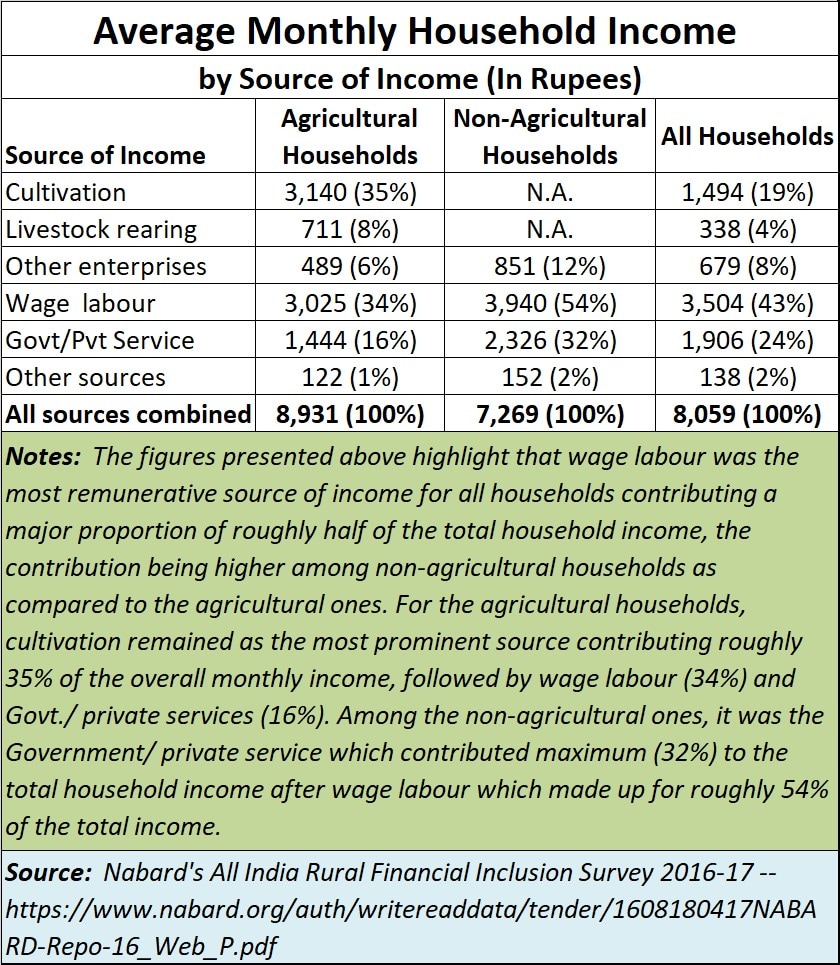

In Budget 2020, it is fervently hoped that the government will focus on genuinely empowering the farm sector. It is a hope that this will not be done through doles and sops, as has been the case quite often. One hopes that the government will be capable of making some fundamental changes in the way it views agriculture and farm remuneration. Impoverished farmers First, contrary to what most people believe, the average farmer earns pathetically little (see chart).

The data—which has been compiled by NABARD shows that income from cultivation is pathetically low. The farmer usually augments this income through other means of livelihood. Had he depended only on cultivation, he and his family would have to die of starvation. That could explain why the highest number of suicides can be found among farmers. Of course, these are average figures. For instance, while the average farmer gets only Rs 711 a month from livestock rearing, farmers in Gujarat and Tamil Nadu and other progressive states get around Rs 100 per milch cattle per day for 300 days a year (the remaining days the cattle are allowed to go dry to prepare for the next round of insemination and lactation). So, even one cattle head could have generated around Rs 3,000 for the farmer per month, not Rs 711. And most farmers have two or three cattle in their backyard on an average. The reason the figure is low is that most farmers are exploited in most parts of the country. Except in the states where the Verghese Kurien-type cooperative movement is strong, or where there are progressive corporate players like Hatsun, Heritage or Nestle, farmers get precious little for the milk they produce. Somehow, many state governments have not worked towards ensuring that farmers get the same price for milk that farmers in Gujarat or Tamil Nadu get. That is a shame. Look at the incomes of farmers state-wise—figures once again taken from NABARD. The so-called progressive states like |Andhra Pradesh, even Maharashtra, can be quite exploitative. Farmers in Gujarat do earn a lot more, but not as much as farmers in states like Kerala and Punjab, where farmers are less exploited, and the states have taught them to go in for value addition. And this brings us to the crux of the problem confronting agriculture. Except for pampered farmers who grow rice and wheat (where the Food Corporation of India (FCI) procures their produce), and plantation growers, most other farmers get pathetically for their farm produce. Vegetable growers get barely 10 percent of the market price for their produce. Growers of grains like pulses are lucky to get 30 percent.

The data—which has been compiled by NABARD shows that income from cultivation is pathetically low. The farmer usually augments this income through other means of livelihood. Had he depended only on cultivation, he and his family would have to die of starvation. That could explain why the highest number of suicides can be found among farmers. Of course, these are average figures. For instance, while the average farmer gets only Rs 711 a month from livestock rearing, farmers in Gujarat and Tamil Nadu and other progressive states get around Rs 100 per milch cattle per day for 300 days a year (the remaining days the cattle are allowed to go dry to prepare for the next round of insemination and lactation). So, even one cattle head could have generated around Rs 3,000 for the farmer per month, not Rs 711. And most farmers have two or three cattle in their backyard on an average. The reason the figure is low is that most farmers are exploited in most parts of the country. Except in the states where the Verghese Kurien-type cooperative movement is strong, or where there are progressive corporate players like Hatsun, Heritage or Nestle, farmers get precious little for the milk they produce. Somehow, many state governments have not worked towards ensuring that farmers get the same price for milk that farmers in Gujarat or Tamil Nadu get. That is a shame. Look at the incomes of farmers state-wise—figures once again taken from NABARD. The so-called progressive states like |Andhra Pradesh, even Maharashtra, can be quite exploitative. Farmers in Gujarat do earn a lot more, but not as much as farmers in states like Kerala and Punjab, where farmers are less exploited, and the states have taught them to go in for value addition. And this brings us to the crux of the problem confronting agriculture. Except for pampered farmers who grow rice and wheat (where the Food Corporation of India (FCI) procures their produce), and plantation growers, most other farmers get pathetically for their farm produce. Vegetable growers get barely 10 percent of the market price for their produce. Growers of grains like pulses are lucky to get 30 percent.

.jpg) This is a far cry from what Verghese Kurien of the White Revolution fame wanted. He always said that the

most important player

was the farmer. He had to earn more than the processor, the trader and the marketing distribution guys. His minimum benchmark was 50 percent but he managed to ensure that Gujarat’s farmers got 80-85 percent of the market price for their milk. Compare this with the 10 percent that vegetable growers get, or the 30 percent other grain producers get. Therefore, when the prime minister talks about doubling farmer incomes, it is inadequate. The farmer should get at least 50 percent (doubling would mean just 20 cent for the vegetable grower). How does one do this? Simple. Just get the FCI to purchase (non-rice and wheat) grain from the commodity exchanges at the minimum support price (MSP) declared by the government. Without procurement, the MSP is only a paper figure, and is a joke. Both MCX and NCDEX had proposed this. But the government continues to sleep over this proposal. Even a 5 percent procurement will compel traders to pay the farmers more. That will allow the farmers to earn more, even though it will mean squeezing the traders. The government can urge corporates and malls to enter into contract farming agreements with farmers for offtake of vegetables—but at 50 percent of the market price. There are many other things that the government can do. Just push for such changes through the budget. Don’t make a beggar out of farmers through doles. Don’t teach him to be dishonest through loan waivers. Create a method for him to earn more. And please ensure that imports do not destroy

market prices,

ever. Do remember that this is what almost happened when some bright boys from the commerce ministry almost allowed New Zealand to seal 5 percent of its exports to India. The farmer lobbies howled in protest, and media reports showed how

stupid these bright boys

could be. Thanks to those protests, the government suddenly had the good sense to back off.

This is a far cry from what Verghese Kurien of the White Revolution fame wanted. He always said that the

most important player

was the farmer. He had to earn more than the processor, the trader and the marketing distribution guys. His minimum benchmark was 50 percent but he managed to ensure that Gujarat’s farmers got 80-85 percent of the market price for their milk. Compare this with the 10 percent that vegetable growers get, or the 30 percent other grain producers get. Therefore, when the prime minister talks about doubling farmer incomes, it is inadequate. The farmer should get at least 50 percent (doubling would mean just 20 cent for the vegetable grower). How does one do this? Simple. Just get the FCI to purchase (non-rice and wheat) grain from the commodity exchanges at the minimum support price (MSP) declared by the government. Without procurement, the MSP is only a paper figure, and is a joke. Both MCX and NCDEX had proposed this. But the government continues to sleep over this proposal. Even a 5 percent procurement will compel traders to pay the farmers more. That will allow the farmers to earn more, even though it will mean squeezing the traders. The government can urge corporates and malls to enter into contract farming agreements with farmers for offtake of vegetables—but at 50 percent of the market price. There are many other things that the government can do. Just push for such changes through the budget. Don’t make a beggar out of farmers through doles. Don’t teach him to be dishonest through loan waivers. Create a method for him to earn more. And please ensure that imports do not destroy

market prices,

ever. Do remember that this is what almost happened when some bright boys from the commerce ministry almost allowed New Zealand to seal 5 percent of its exports to India. The farmer lobbies howled in protest, and media reports showed how

stupid these bright boys

could be. Thanks to those protests, the government suddenly had the good sense to back off.

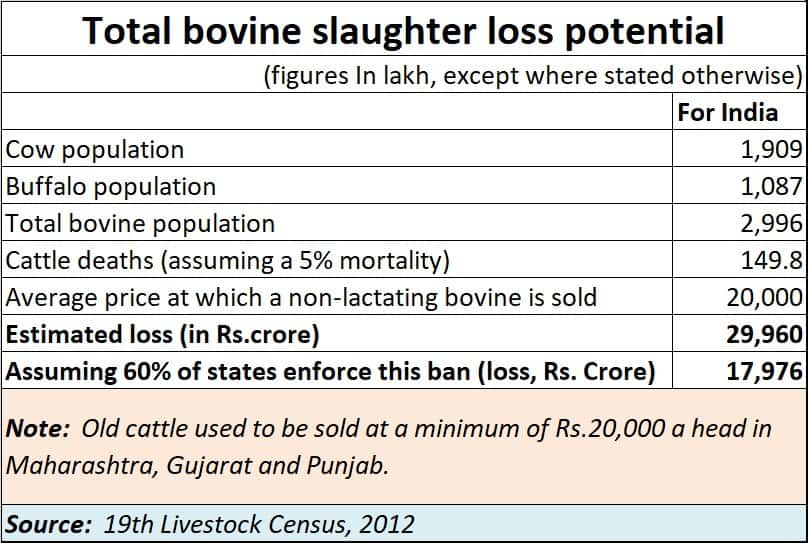

The losses on account of the ban on bovine slaughter could be costing the farmers—on the aggregate—anywhere between Rs 18,000 crore to Rs 30,000 crore (see table above). And this is without counting the losses in future income for the farmer, the losses caused to the cobbler and the leather merchandise industry and to the carabeef industry as well. It is time this madness is stopped, because one of the reasons for farm distress is the squeeze on cashflow and revenue generation because of these frenzied mobs who seek to stop meat wagons. The Budget must make a mention of this if the government want to show the country the solution to achieve an economic revival. Dear Finance Minister, you know how

the country is hurting

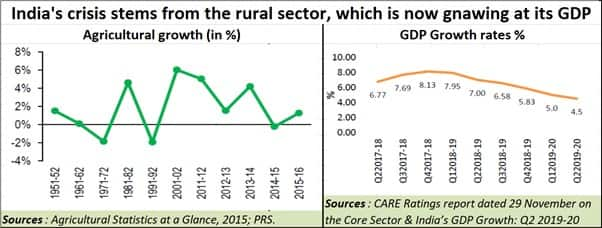

. And if you look closely, much of this hurt is on account of the distress in the rural sector (see chart).

The losses on account of the ban on bovine slaughter could be costing the farmers—on the aggregate—anywhere between Rs 18,000 crore to Rs 30,000 crore (see table above). And this is without counting the losses in future income for the farmer, the losses caused to the cobbler and the leather merchandise industry and to the carabeef industry as well. It is time this madness is stopped, because one of the reasons for farm distress is the squeeze on cashflow and revenue generation because of these frenzied mobs who seek to stop meat wagons. The Budget must make a mention of this if the government want to show the country the solution to achieve an economic revival. Dear Finance Minister, you know how

the country is hurting

. And if you look closely, much of this hurt is on account of the distress in the rural sector (see chart).

Some of this could be explained away as administrative oversight. Some of it may require a policy rethink. And some of it has to do with law and order, and the need to ensure that cash flows of the rural sector, the leather industry and the carabeef export industry are not adversely affected. Do this, and the government can hope for an economic revival within six months—the farming sector will become buoyant, and cash flows will return. That will trigger purchasing power, and in turn the wheels of industry will begin to move faster. (The writer is a senior journalist. He tweets @rnbhaskar1) Follow full coverage of Union Budget 2020-21 here

Some of this could be explained away as administrative oversight. Some of it may require a policy rethink. And some of it has to do with law and order, and the need to ensure that cash flows of the rural sector, the leather industry and the carabeef export industry are not adversely affected. Do this, and the government can hope for an economic revival within six months—the farming sector will become buoyant, and cash flows will return. That will trigger purchasing power, and in turn the wheels of industry will begin to move faster. (The writer is a senior journalist. He tweets @rnbhaskar1) Follow full coverage of Union Budget 2020-21 here

Budget 2020: Govt must give priority to agriculture, empower farm sector to revive economy; don't hand out doles and sops

RN Bhaskar

• January 31, 2020, 12:45:50 IST

In Budget 2020, it is fervently hoped that the government will focus on genuinely empowering the farm sector.

Advertisement

)

Revival through the rural sector Why should the farmer be so crucial? There are at least three reasons which explain why the rural sector is crucial for an economic revival. First, remember that 50 percent of India’s population depends on agriculture. When 50 percent of India’s population of 1.3 billion depend on this sector, the government just cannot ignore it. It is part of the economy, even if it contributes just 14 percent to India’s GDP. Also remember, that the rural economy contributes only 14 percent because its produce is priced very low. Pay 50 percent of the market price, and the contribution of this sector will swell to 25 percent. Second, do appreciate the fact that unlike all the Asian tigers—South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan and the like—which grew because they were export-oriented, India is not an exporting economy. It is a consumption story. So if consumption is good, industry does well, and it can export as well. Hurt consumption, and you hurt industry and you also hurt exports. And that brings us to the third inescapable realisation that consumption depends also on the 650 million people staying in rural areas. That this 50 percent of India’s population is a purchasing community. It needs to purchase seeds, fertilisers, cement for houses and canals, harvesting equipment, tractors and motorcycles among others. And it purchases consumer products as well. If this 50 percent loses purchasing power, it purchases less. That hurts industry, and the slowdown can become acute. That is why the purchasing power that the rural sector enjoys is crucial for India’s economic revival. That is also one more reason why the Budget should categorically warn frenzied mobs who stop meat wagons under the specious excuse that the meat could be cow’s meat. Much of the meat coming to the market currently is buffalo meat. If the government want to protect cows, do so, but why hurt buffalo owners? In any case, in states where this gau rakshak madness has become frenzied, most farmers are switching over to buffaloes. That helps also because buffalo milk has more fat content. So the farmer gets more money for buffalo milk than for cow’s milk. But when a meat wagon is stopped, even if the trader’s life is dpared, the meat becomes rotten, unfit for human consumption, if it lies around for more than a few hours. The trader loses money, and he resolves not to purchase old cattle from farmers any more. The trouble is that the farmer gets around Rs 20,000 for each old cattle head. If he cannot sell the old buffalo, he loses Rs 20,000. He used to add another Rs 20,000 (sometimes even by borrowing this sum) to purchase a new buffalo. Now he cannot do so because the seed capital of Rs 20,000 is not forthcoming. Worse, he has additional expenses because he has to look after old cattle. As a result, the farmer loses purchasing power. The leather and beef industries which are both employment generators and forex earners lose money, and the economic depression becomes more severe.

End of Article