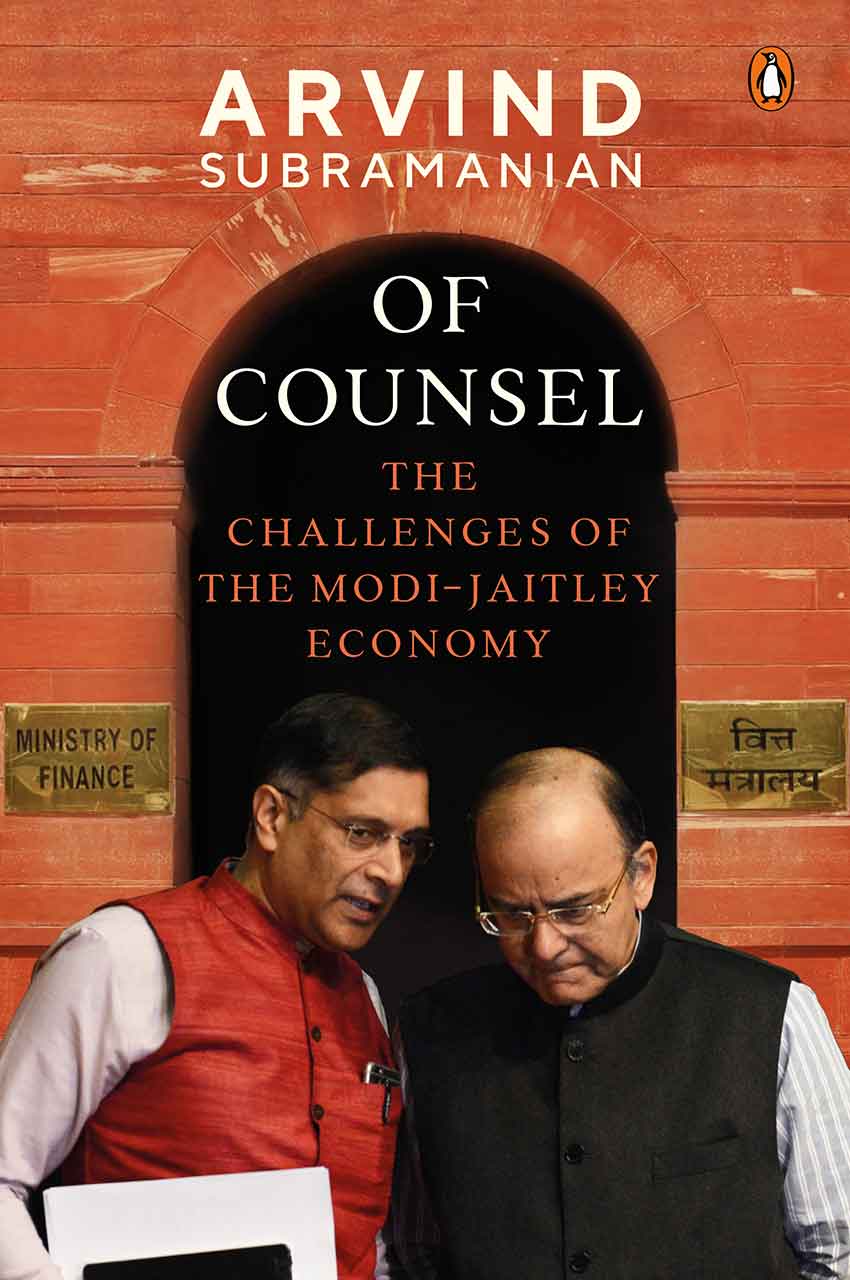

Former Chief Economic Advisor Arvind Subramanian in his soon-to-be-published new book, Of Counsel: The Challenges of the Modi-Jaitley Economy, has touched upon a slew of issues from capitalism, socialism to demonetisation, GST and a host of other topics. In an excerpt from the book on demonetisation, Subramanian discusses the ‘political popularity’ of the government’s reform. Excerpts have been reproduced with permission from Penguin Books India. On 8 November, in a dramatic nationally televised speech that I watched in my room in North Block, the prime minister announced that the top two high-denomination currency notes of Rs 500 and Rs 1000 would cease to be legal tender; that is, they would no longer be accepted as a government-certified means of payment. It was an [caption id=“attachment_4074559” align=“alignleft” width=“380”] File photo of Arvind Subramanian. Image courtesy: PIB[/caption] unprecedented move that no country in recent history had made in normal times. The typical pattern had either been gradual demonetizations in normal times (such as the European Central Bank phasing out the 500-euro note in 2016) or sudden demonetizations in extreme circumstances of war, hyperinflation, currency crises or political turmoil (Venezuela in 2016). The Indian initiative was, to put it mildly, unique. It presupposed an extraordinary amount of resilience in the economy, especially amongst the vulnerable, because it was going to be the first of two major shocks—along with the GST—to affect those in the cash-intensive, informal sectors of the economy. Two years on, demonetization still consumes the attention of the commentariat, in part because of the mysteries surrounding its origins. I have little to add to the economics of the D-decision beyond what was said in three economic surveys that I oversaw. I do have some new thoughts, or rather hypotheses, on two demonetization puzzles, political and economic.

Puzzle 1: Why was demonetization so popular politically if it imposed economic costs? Specifically, why did demonetization turn out to be an electoral vote winner in the short-term (in the Uttar Pradesh elections of early 2017) if it imposed so much hardship on so many people? Today, the political perception of demonetization is confounded by a slew of economic and political developments that have occurred since November 2016. Clearly, many factors influence voters’ perceptions and hence affect outcomes, rendering any attempt to tease out cause and effect as unreliable. It is important, however, not to forget history as it happened. At the time (early 2017), the election in Uttar Pradesh—India’s most populous state and the world’s eighth-largest ‘country-thatisn’t’—was widely seen as a verdict on demonetization, arguably the salient policy action of the government, personally and forcefully articulated by the prime minister. The demonetization experiment speaks to the more pervasive and fascinating global phenomenon of What’s the Matter with Kansas?, the title of a famous book by American historian Thomas Frank. This book explores the apparent paradox of citizens voting against their economic self-interest. For example, why do poor white males vote for the Republican Party and President Trump when the policy agenda either has no benefits to them (tax cuts for the rich) or is positively harmful (undermining Obamacare and welfare benefits more broadly)? That same question seemed relevant after the resounding victory of the NDA government in the UP election. This particular piece is an attempt to understand that result as a disinterested observer armed only with publicly known facts. It is not an explanation of the motives of demonetization, simply a post facto analysis of one apparently fascinating political outcome associated with it. How could demonetization that is supposed to have adversely affected so many Indians—the scores of millions dependent on the cash economy—be so resoundingly supported by the policy’s very (and numerous) victims? I offer the controversial hypothesis that imposing large costs on a wide cross-section of people (and the fact that the Rs 500 and not just the Rs 1000 note was demonetized increased the scope and scale of demonetization’s impact), unexpected and unintentional though it may have been, could actually have been indispensable to achieve political success. The canonical political economy model of trade explains the persistence of protectionism in terms of an imbalance between the gainers and losers. Protection—which raises domestic prices—helps a few domestic producers a lot while diffusing the harm among many consumers, each of whom loses only a little. Producers, therefore, have both an incentive and ability to lobby for protection, while individual consumers have little incentive to lobby against it. The demonetization case has been very different: hardship was imposed on many and possibly to a great extent, and yet they appear to have been its greatest cheerleaders. One answer to the demonetization puzzle has been that the poor were willing to overlook their own hardship, knowing that the rich and their ill-begotten wealth were experiencing even greater hardship: ‘I lost a goat but they lost their cows.’ In this view, the costs to the poor were unavoidable collateral damage that had to be incurred for attaining a larger goal. This is not entirely convincing. After all, the collateral damage was in fact avoidable. Anti-elite populism, or ‘rich bashing’, as the Economist put it, could have taken the form of other punitive actions—taxation, appropriation, raids—targeted just at the corrupt rich. Why entangle the innocent masses and impoverish them in the bargain? As I wrote in the Economic Survey of 2016–17, if subsidies are a highly inefficient way of transferring resources to the poor, demonetization seemed a highly inefficient way of taking resources away from the rich. Understanding the political economy of demonetization may require us, therefore, to confront one overlooked possibility— that adversely impacting the many, far from being a bug, could perhaps have been a feature of the policy action. Not necessarily by design or in real time, but in retrospect it appears that impacting the many adversely may have been intrinsic to the success of the policy. Consider why.

Puzzle 1: Why was demonetization so popular politically if it imposed economic costs? Specifically, why did demonetization turn out to be an electoral vote winner in the short-term (in the Uttar Pradesh elections of early 2017) if it imposed so much hardship on so many people? Today, the political perception of demonetization is confounded by a slew of economic and political developments that have occurred since November 2016. Clearly, many factors influence voters’ perceptions and hence affect outcomes, rendering any attempt to tease out cause and effect as unreliable. It is important, however, not to forget history as it happened. At the time (early 2017), the election in Uttar Pradesh—India’s most populous state and the world’s eighth-largest ‘country-thatisn’t’—was widely seen as a verdict on demonetization, arguably the salient policy action of the government, personally and forcefully articulated by the prime minister. The demonetization experiment speaks to the more pervasive and fascinating global phenomenon of What’s the Matter with Kansas?, the title of a famous book by American historian Thomas Frank. This book explores the apparent paradox of citizens voting against their economic self-interest. For example, why do poor white males vote for the Republican Party and President Trump when the policy agenda either has no benefits to them (tax cuts for the rich) or is positively harmful (undermining Obamacare and welfare benefits more broadly)? That same question seemed relevant after the resounding victory of the NDA government in the UP election. This particular piece is an attempt to understand that result as a disinterested observer armed only with publicly known facts. It is not an explanation of the motives of demonetization, simply a post facto analysis of one apparently fascinating political outcome associated with it. How could demonetization that is supposed to have adversely affected so many Indians—the scores of millions dependent on the cash economy—be so resoundingly supported by the policy’s very (and numerous) victims? I offer the controversial hypothesis that imposing large costs on a wide cross-section of people (and the fact that the Rs 500 and not just the Rs 1000 note was demonetized increased the scope and scale of demonetization’s impact), unexpected and unintentional though it may have been, could actually have been indispensable to achieve political success. The canonical political economy model of trade explains the persistence of protectionism in terms of an imbalance between the gainers and losers. Protection—which raises domestic prices—helps a few domestic producers a lot while diffusing the harm among many consumers, each of whom loses only a little. Producers, therefore, have both an incentive and ability to lobby for protection, while individual consumers have little incentive to lobby against it. The demonetization case has been very different: hardship was imposed on many and possibly to a great extent, and yet they appear to have been its greatest cheerleaders. One answer to the demonetization puzzle has been that the poor were willing to overlook their own hardship, knowing that the rich and their ill-begotten wealth were experiencing even greater hardship: ‘I lost a goat but they lost their cows.’ In this view, the costs to the poor were unavoidable collateral damage that had to be incurred for attaining a larger goal. This is not entirely convincing. After all, the collateral damage was in fact avoidable. Anti-elite populism, or ‘rich bashing’, as the Economist put it, could have taken the form of other punitive actions—taxation, appropriation, raids—targeted just at the corrupt rich. Why entangle the innocent masses and impoverish them in the bargain? As I wrote in the Economic Survey of 2016–17, if subsidies are a highly inefficient way of transferring resources to the poor, demonetization seemed a highly inefficient way of taking resources away from the rich. Understanding the political economy of demonetization may require us, therefore, to confront one overlooked possibility— that adversely impacting the many, far from being a bug, could perhaps have been a feature of the policy action. Not necessarily by design or in real time, but in retrospect it appears that impacting the many adversely may have been intrinsic to the success of the policy. Consider why.

Two years on, demonetisation still consumes the attention of the commentariat, in part because of the mysteries surrounding its origins, says Arvind Subramanian.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)