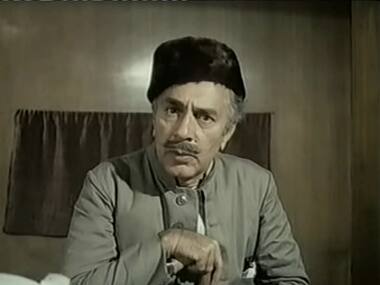

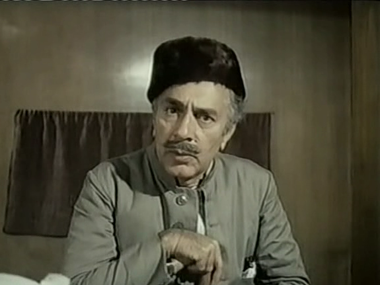

MS Sathyu’s Garam Hava may be in a multitude of “best film” lists, but had the Central Board of Film Certification had its way, back in 1974, it may never have seen the light of day. The CBFC gave the film a rejection certificate, saying Garam Hava could incite communal tensions. It’s one of those decisions that makes you wonder whether the CBFC actually watches the films that are submitted for certification or just has knee-jerk reactions. It seems the board didn’t notice the sensitively-etched characters or the elegantly balanced script set in post-Partition Agra, where a Muslim man chooses to stay on in India, rather than go to Pakistan. All the CBFC saw and was unnerved by, it seems, was the frustrated sadness of Salim Mirza and his family. So much so that they rejected the film. However, this didn’t actually stop Garam Hava from getting a theatrical release. Someone with serious muscle backed the film against the CBFC: Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. She insisted the film be passed without any cuts, and so it was that Garam Hava opened in Indian theatres, in 1974. [caption id=“attachment_1799353” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  Courtesy: Wikipedia[/caption] Forty years later, the film, lovingly restored, is about to be re-released this Friday. You’d think that a film set in 1947 and made in the early 1970s would feel dated in 2014. Curiously, it doesn’t because while the circumstances have changed, the issues in Garam Hava remain relevant today. Whether it’s the shame and heartbreak of being jilted, the frustration at being qualified but unemployed or struggling with stereotypes, much of Garam Hava is still real and relatable. The difference is in the world surrounding the film — can you imagine Prime Minister Narendra Modi using his considerable powers to ensure a tiny little indie film gets released? Film and politics have long flirted with each other in India. The glamour of film and the power of politics aren’t so much married as engaged in a long and torrid affair that has got increasingly tawdry over time. While Prime Minister Narendra Modi is clicking selfies with the likes of Sonam Kapoor and Bollywood is showing up at his Mumbai events with the obedience of students attending school assemblies, it’s worth noticing that it’s only the commercial and the mainstream that our PM has chosen to befriend. The intellectuals — pseudo or otherwise — are not invited to the party. They are left to languish and grind their teeth in their niches. The reasoning is simple enough: if you want to reach out and make an impression upon the largest group of people, then you ride with what is popular. Thanks to how cannily Modi has crafted his public image and publicity campaign, he has perhaps a larger fan base than most Bollywood stars, but the presence of actors like Kareena Kapoor and Aamir Khan make Modi’s photo ops far glossier than the average politician’s mug shot. Wittingly or unwittingly, Bollywood helps Modi grab the attention of those who wouldn’t attend his rallies or follow ‘serious’ news. Meanwhile, Modi’s presence assures the actors a few moments in a brighter spotlight and showing up on the front page as opposed to the back pages usually occupied by entertainment. Bollywood wasn’t any less glamorous in Indira Gandhi’s time. It wasn’t as professional or organised as an industry, but it had pretty faces and its stories, on and off screen, captured the imaginations of a swathe of the country. There are photographs showing Gandhi posing for the camera with actors. In one, she’s very much the queen bee in a cluster of beaming, formally dressed heroes, including Raj Kapoor, Dev Anand and Mehmood. Gandhi knew the reach and persuasive powers of films, which is why Gulzar’s Aandhi faced as many hurdles as it did. In sharp contrast to Garam Hava, Aandhi was passed by the CBFC but banned by the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. The film had been publicised as a story based on Gandhi’s life with Suchitra Sen playing Aarti Devi, whose mannerisms and appearance were clearly modelled on Gandhi and Sanjeev Kumar playing a character based on Gandhi’s husband, Feroze. Aandhi is about as sympathetic a portrait as you could imagine of a woman politician, but Gandhi wasn’t amused. She had a carefully-crafted image of one who had entered politics because the nation needed her to follow in her father’s footsteps and she wasn’t going to risk a film making her out to be something negative, like a driven, somewhat selfish, career woman. So Aandhi was banned just before its release and this made headlines all over the world. Gulzar gave statements denying the film was based on Gandhi’s life. (He would take these back a few years later, when Gandhi was out of power.) New edits were made, including inserting a scene in which Aarti Devi stands in front of a photograph of Gandhi and says she’d like to serve the nation the way Gandhi has. Aandhi had a limited release in 1975 and was banned during the Emergency. It was only after the elections of 1977, in which Gandhi and Congress suffered a defeat, that the film became popular. The new Minister of Information and Broadcasting had Aandhi telecast on Doordarshan. Yet, just a year before Aandhi, when she was just a hop skip and jump away from gagging the nation with Emergency in 1975, Gandhi flexed her muscles for Garam Hava. Sathyu’s film wasn’t enamoured by either politics in general or the Congress party in particular. Politicians are opportunists in Garam Hava and the state is almost powerless. It only adds to people’s woes and ends up harassing them with its lack of understanding of people’s travails. Sathyu’s film showed how the state had failed citizens and raised uncomfortable questions about belonging and identity politics. Yet this was the film that Gandhi helped through the censors. Gandhi may not have realised Garam Hava would go on to acquire such iconic proportions. Perhaps she figured the truly indie film — it cost Rs 10 lakhs to make, of which Rs 7.5 lakhs were from loans that Sathyu scrabbled together — was far less of a threat than a commercial film. Perhaps she didn’t give a damn about cinema, commercial or indie, and just had a few cinephiles among her advisors. Whatever the reason, the curious truth is that Gandhi ended up championing independent cinema, peopled as it was with directors, writers and actors who were idealistic and unwilling to keep the peace by being politely quiet. A year later, she enforced Emergency upon India. Here’s a nugget to ponder over: in past interviews, Narendra Modi has said that one of the people he admires is Indira Gandhi. And the scorching winds of Garam Hava are still blowing. Garam Hava releases on Friday, November 14, as part of PVR’s Director’s Rare series.

Gandhi may not have realised Garam Hava would go on to acquire such iconic proportions.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)