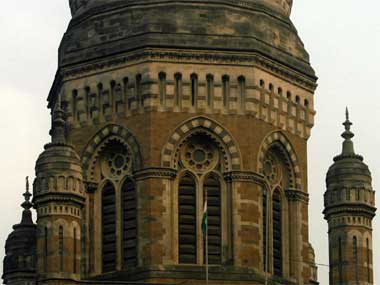

Here are a few quotes from a judgement delivered in 1980 by Justices VR Krishnaiyer and O. Chinnapa Reddy when the then nondescript Ratlam town’s municipality had refused to build drains to arrest free flow of sewage from a slum. The civic body had pleaded financial insufficiency to undertake the work but this is what the court said: - It couldn’t “run away from its principal duty by pleading financial inability. Decency and dignity are non- negotiable facets of human rights and are a first charge on local self-governing bodies”; - Plea of poor finance will be poor alibi; - Financial inability does not “validly exonerates it from statutory liability” and “ has no juridical basis”; - “Such doleful statements” on financial capability “had no meaning”; The court’s observations came during what was the first public interest litigation which “activated the tort consciousness” among the elected representatives, and which, if only had been used as a precedent by citizens across the country, could have seen a better system of people-centric city governments. Having said that, it needs to be explained why this case has been exhumed from the records. [caption id=“attachment_1296801” align=“alignleft” width=“380”]  Reuters[/caption] The country’s richest (in terms of budgetary allocations) is the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai which saw itself as the custodian of Urbs prima Indis – the primary, or the greatest city in India. The civic body, it turns out, has never pleaded financial inadequacy to the extent the Ratlam Municipality had. Compared to other civic bodies, the MCGM is often wallowing in funds. The demands of Mumbai are also different from several other major Indian cities. However, this current fiscal year the civic body has found itself unable to spend what it had budgeted, which is a shame. The Indian Express reported two days ago that the MCGM, also known as BMC (an acronym for Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation) had managed to spend only 30 percent of the funds allocated to various departments. A day later, The Times of India disclosed it had spent “only 17 per cent of its annual funds”. The current year’s budget size is Rs 27,578-crore which is a 23 percent increase over last year’s budget. For 2012-13, it was Rs 26,581 crore, which itself was a 26 percent increase over the 2011-12’s Rs 21,096 cr. It is possible that those who matter may quibble on the quantum mentioned as proportion of expenditure against the budgetary allocations, but the fact remains that despite the wide gap, the money remains unspent. Even the probable silver lining, that money unspent was saved, isn’t there because, as The Times of India reported, the civic body in the next three-four weeks will clear projects worth Rs 3,500 cr. There is no doubt a sense of urgency because the Election Commission is seen announcing that the Lok Sabha poll process will start by mid-March and the Lok Sabha could be in place by 1 June. Once the election process starts, the civic body, mainly its ruling political party, will not be able to start work and claim credit. Their compulsions are strengthen because soon after those elections the state’s Assembly polls are to be held within a few months. The model code of conduct would stymie any milking of political advantage. Knowing – and this could well be marked down as a cynical perspective – how the tendering processes operate, how bids are selected and how money is made, it would be a valid suspicion that civic body funds could fund election campaigns. Big ticket projects have their own political lures. Perhaps a single project in Mumbai – like the Rs 500 cr tender for storm water drains that will come up for approval in a hurry – could finance Ratlam municipality for a long time. Amritsar which boasts of an international airport has an annual budget of Rs 300 cr. On the other hand despite the funds allocated, the civic body cannot, or more accurately, does not spend. A plethora of excuses like revision of standards, or rates, legal issues will be trotted out to explain the gap in allocations of funds and spending. The Indian Express points out that it was better last year: the MCGM had spent 19 per cent of the budget meant for works. Perhaps some comfort can be drawn from the fact that there are still four months left for the civic body to spend its funds. Year upon year, this has been the case – increased budget size, and abysmally lower expenditure, barring the establishment costs like salaries and allowances. The surprising aspect is major issues, which not mere spending but execution of work, has seen lower outgoes – for instance, only 16 per cent in 2004-5. Spending is a measure of efficiency in India, where the administration was happy with mere allocations even if there was nothing in the treasuries of any department of any government. The measure changed to outcomes, and was first acknowledged as a requirement and was advocated by P Chidambaram in his Union Budget. But we do not know how outcomes are now measured, especially in MCGM, except apparently by the size of the budget. If there were good schools run by the MCGM then they are declining in numbers, enrolments have dropped and dropout rates have not significantly changed. Health indices are generally as poor as they were a year ago. Roads are in tatters. The Ratlam judgement when read in full ( text here) shows the underlying concern that no matter the issue of funds, a civic body has to perform, if required, by cutting out low-priority items. Mumbai is at the other end – huge budgets, poor expenditure, and with no measure of outcomes.

This current fiscal year the civic body has found itself unable to spend what it had budgeted, which is a shame.

Advertisement

End of Article

Written by Mahesh Vijapurkar

Mahesh Vijapurkar likes to take a worm’s eye-view of issues – that is, from the common man’s perspective. He was a journalist with The Indian Express and then The Hindu and now potters around with human development and urban issues. see more

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)