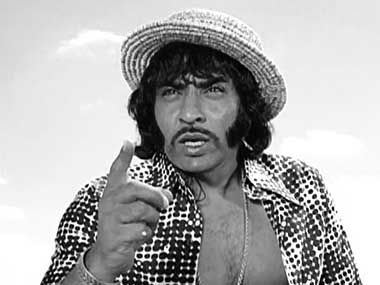

By Deepa Deosthalee In January 2011, a Toronto police constable addressing a forum at York University about crime prevention made the comment, “women should avoid dressing like sluts in order not to be victimised.” His statement sparked off a worldwide agitation called Slutwalk, whereby women in various cities around the world have taken to the streets to protest against their objectification and to fight for their right to dress as they please without fear of being violated. Next month, Slutwalk comes to Delhi, perhaps the most unsafe city for women in a country that is considered one of the most dangerous places on earth for them. Since the provocation of this movement was the constable’s claim that women leave themselves open to rape because of the way they dress (a view that is rampant in our society), it may be pertinent to examine how our cinema handles the sexual violation of women and to what extent the objectification and chastisement of women is central to the narrative of rape. In Mehboob Khan’s Mother India (1957), Radha’s (Nargis) attempted rape by the lascivious moneylender Sukhilala (Kanhaiyalal) is crucial to the screenplay and to her elevation from an ordinary woman to Mother India. She refuses to sell her body even to feed her starving children, but the point is — Sukhilala believes that in the absence of her husband and in view of her impoverishment, she is fair game. Till nearly two decades after Mother India, although attempted rape continued to be a sub-plot in many Hindi films, more often than not, the heroine was rescued from the villain’s clutches in the nick of time, like the heroines of the Ramayan and Mahabharat, whose chastity was preserved on account of their inherent ‘purity’. Still popular villain of the 1970s, Ranjeet earned himself the notoriety of having committed a record 350 screen rapes! [caption id=“attachment_28735” align=“alignleft” width=“380” caption=“Ranjeet. Image from Filmimpressions blog”]  [/caption] A woman’s ‘izzat’ The film that brought rape to the forefront of the narrative space was B R Chopra’s Insaaf Ka Tarazu (1980). Coming as it did at the end of a decade in which the feminist movement was taking firm roots in India and women in urban areas were joining the workforce in unprecedented numbers, Insaaf Ka Tarazu, made by one of the pillars of Bollywood patriarchy, voices the male establishment’s anxiety over women’s liberation. Bharati (Zeenat Aman) an independent working woman, is a well-known model — a profession that commodifies women most blatantly. Playboy Ramesh Gupta (Raj Babbar) is so enamoured by her, he can’t stop drooling from the minute he sets eyes on her. Soon he visits her on an ad film shoot on the beach. We see Bharati, dressed in a semi-transparent night-gown and the director telling her, “Come on Bharati, I want more sex!” She has been objectified long before Ramesh denudes her. Ramesh rapes her on being spurned, but not before he assaults her verbally and physically, tears up her clothes and makes her grovel at his feet. The director takes his time delineating this sequence, and also the subsequent rape of Bharati’s younger sister Nita (Padmini Kolhapure). The court case is a sham and another chapter in the assassination of Bharati’s character. Ramesh is acquitted for lack of evidence and goes on to force himself on Nita, before Bharati finally empties a gun into him and pleads guilty for murder. Unlike the avenging heroes of the ‘angry young man’ films where vendetta is a man’s to take, Bharati must justify herself to the patriarchal establishment in court. But the greater harm that Insaaf Ka Tarazu did was on account of the way it constructed its schizophrenic protagonist, a woman who may be liberal enough to take up a career in modelling, but is seeped in regressive tradition. In the ‘avenging women’ sub-genre that Insaaf Ka Tarazu spawned, there were many films focusing on urban women who are raped, humiliated and denied justice, before they take recourse to violence and avenge themselves. Prominent amongst these was Avatar Bhogil’s Zakhmi Aurat (1988) where a policewoman (Dimple Kapadia), after being raped, forms a gang of avenging angels who go about delivering justice by castrating rapists. Continue reading on page 2 Domestic bliss shattered Manik Chatterjee’s Ghar (1978) is about a young couple, Vikas and Aarti (Vinod Mehra and Rekha), who are accosted by four goons on a deserted road late at night. Aarti is abducted and gang-raped— here the director spares us a graphic representation of the woman’s humiliation (standard issue in our cinema). The couple struggles to overcome this traumatic episode, even though Vikas is a caring and supportive husband. But Aarti can’t shake off her sense of guilt and humiliation. What the film effectively portrays is the voyeuristic pleasure society at large derives from rape — people read newspaper articles about the incident with relish, ask pointed questions or then, shun contact with the victim. Video from Ghar In Rajkumar Santoshi’s Damini (1993) the maid of the house is gang-raped by the younger son and his friends after drunken revelry on Holi day. Damini (Meenakshi Seshardri), the upright daughter-in-law witnesses the rape and her determination to speak the truth not only alienates her from her family, but also drives her to a mental asylum and is ultimately raped by proxy in court by the ruthless defence lawyer who asks her to describe what she saw in minute detail and cross-examines her as though she was guilty of a grave offence. [caption id=“attachment_28720” align=“alignleft” width=“380” caption=“Damini. Image from FilmImpressionsBlog”]  [/caption] Damini, while purporting to be a mainstream ‘feminist’ narrative, is essentially another chapter in the degradation of women on screen. The emphasis from the male-centric worldview doesn’t shift an inch, even when the woman is supposedly in the foreground. Body as battlefield Following the release of Shekhar Kapur’s critically acclaimed Bandit Queen (1994) based on the book by Mala Sen that chronicled the life of Phoolan Devi, Arundhati Roy wrote a scathing critique of the film and of Kapur’s ‘middle-class outrage’ against Phoolan’s character. Roy writes, “According to Shekhar Kapur’s film, every landmark — every decision, every turning-point in Phoolan Devi’s life, starting with how she became a dacoit in the first place, has to do with having been raped, or avenging rape… It’s a sort of reversed male self-absorption. Rape is the main dish. Caste is the sauce that it swims in.” Roy suggests that Kapur constructs his heroine as a victim-avenger (not very different from the avenging angels of the B-movies— except, since he employs a realistic style of storytelling, the violation and humiliation of Phoolan is that much more graphic in its representation) and leaves out critical information about her life that is relevant to the construction of Phoolan Devi’s personality and a part of Sen’s book, but not to Kapur’s imagination of her. Towards the end of Mani Ratnam’s Dil Se (1998), Meghna (Manisha Koirala) narrates to Amar (Shah Rukh Khan) the horrors of the Indian state’s brutality in the North East. While we never see the faces of the men who rape her (as a young girl) and her older sister, the film insinuates that it’s the ugly face of the Indian army. In every conflict zone women pay the price with their bodies which are pulverised. Sudhir Mishra’s Hazaaron Khaiwshen Aisi (2004) depicts the rape of its female lead Geeta (Chitrangada Singh) when she, along with her revolutionary friends, are arrested by the local cops in a remote part of Bihar during the Naxalite movement of the 1970s. The director displays rare sensitivity (as does Ratnam) not just in sparing us the gory details, but also in suggesting that while the episode is traumatic for the heroine when it happens, it doesn’t shape her life and in fact, she goes back to resume her work in the same parts with the same conviction as before. More often than not though, the emphasis is on the humiliation of the victim rather than the issue of patriarchal society’s perversity (as perpetrators, bystanders, voyeuristic consumers and law makers). Or then a flippant subject of ‘comic’ interest as evinced in the infamous scene in Rajkumar Hirani’s 3 Idiots (2009), where Rancho (Aamir Khan) modifies the speech Chatur (Omi Vaidya) is meant to deliver at a college function and replaces the word ‘chamatkaar’ with ‘balaatkaar’. Chatur innocuously delivers the said speech and everyone in the audience (including the Education Minister) laughs hysterically at his faux pas. The Infamous balaatkaar speech from 3 Idiots As does the audience watching the film in the cinema hall. With inputs from Vikram Phukan. Read the whole essay at Film Impressions.

The streets might not be safe for women but are movie scripts any safer? As Slutwalk comes to Delhi next month, here’s a look at how Hindi films handle the sexual violation of women.

Advertisement

End of Article

Written by Film Impressions

Why FILM IMPRESSIONS? Because we believe film lovers deserve better. The quality of film criticism in India has been steadily deteriorating, losing its credibility and intellectual rigour. Instead of informed and unbiased opinion we have been subjected to publicity-driven writing, often manipulated by vested interests. We wish to offer well-argued criticism, insightful interviews, historical perspective... and celebrate cinema in all its glory see more

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)