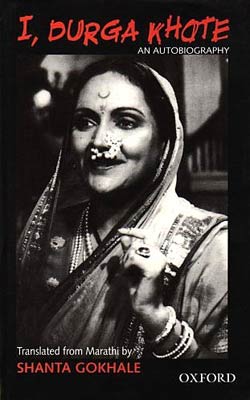

By Vikram Phukan While browsing through titles at a Crossword’s in Mumbai, I came across a book that carried a recommendation by the actress Gul Panag. Now, ordinarily publishers would quote such worthy progenitors of good taste as the New York Review of Books, or the colour supplement of The Hindu or even that most prolific of ‘blurbers’— Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni. It wasn’t quite a ringing endorsement either. Ms Panag said of the book, “It’s such a quick read that I’m surprised I didn’t finish it earlier.” Quite cleverly back-handed there, and I’m sure Panag totally gets the irony, because although celebrities are now ubiquitous at book launches and readings (that’s the sideline that keeps them afloat), they’re usually not the go-to people for literary seals of approval. Not to take anything away from Panag, she is considered one of the few ‘thinking’ actors out there, but that blurb did still seem a little out of whack. Cerebral women – the final frontier It’s not that actresses can’t be smart and clever but we are conditioned to think of the women who inhabit the Indian (read Hindi) silver screen only as glamorous ditzy beings — anything but cerebral. To have a cerebral woman hold sway in a filmi narrative is the final frontier. Housewives have been relegated to cameos, women can now give birth out of wedlock, there have been 10 odd women cops filling out their uniforms wonderfully, but we haven’t really added very many memorable ‘lettered’ women to our roster over the years. There are those smart women who let the men take the credit for all their planning and conniving (like Tabu in Maqbool), or the coquettish types who have perfected feminine wiles to a fine art. But what I’m really talking about are the academic broads who wear their intellectual savvy on their sleeves, or leading women with spunk and nerdiness in equal measure. Instead we get an endless parade of dumb blondes (actually brunettes, since it’s Hindi cinema). The ones who wear horn-rimmed glasses will invariably be in need of a Pygmalion-kind makeover which is usually achieved before the last few reels of the film, just to allow her to shake her booty in a fabulous production number in her new glammed-up avatar. On the other hand, we have had men who’re Nobel-winning scientists, Booker winners, Deans of universities, and orators — Dilip Kumar in Leader pushes Vyjayanthimala to backup vocals in a political rally, but we all know who ended up as a parliamentarian in real life. [caption id=“attachment_52723” align=“alignleft” width=“250” caption=“Image courtesy: Film Impressions”]  [/caption] Women of letters Are there any ‘literary types’ lurching around amongst our actresses? Let’s not count Kareena Kapoor, who has ‘written’ the foreword to her dietician’s book. Let’s not even count Arundhati Roy, who did some acting parts before she became the literary sensation of her times. She played a Santhal tribeswoman in Massey Sahib, and even wrote a script or two for her then-husband Pradeep Kishen but she’s possibly the exception that proves the rule. There have been autobiographies — of Durga Khote, of Vyjayanthimala. The beautiful Leela Naidu gave us Leela: A Patchwork Life (with Jerry Pinto), which was rather a series of candidly recounted anecdotes than a full-blown autobiography. Others have come up with specialized tomes — Persis Khambatta whipped up a book on beauty queens and where they end up in life (and she’d have us believe that all these beauties have brains), and Madhur Jaffrey has trundled out a whole bunch of cookery books and her memoirs, Climbing The Mango Trees, which makes her life seem like a culinary adventure. Then there are writers who’ve made fleeting appearances in films — Ismat Chughtai bringing the fire in her belly to Benegal’s Junoon, and Bapsi Sidhwa revisiting Lahore in the last scene of Deepa Mehta’s Earth, based on her book. In all of this, the spirited Tara Deshpande comes to mind. Fifty & Done was the book she wrote when she was just in her twenties. It was not particularly well-received but it was a whole book. Unfortunately, the curse of the cerebral woman meant that Deshpande, despite the cartloads of spunk she displayed in Bombay Boys, never really had a full innings in the industry. Deepti Naval has brought out two books of poems but she still remains one of our foremost actresses in exile. The greatest of them all was Meena Kumari, who bequeathed a treasure trove of written artifacts to her friend Gulzar, that some people maliciously say has fed his creativity for years — which is not so much an indictment of his own prowess as one of our foremost wordsmiths but more a testament to the tragedienne’s own lost legacy. Continue reading on next page Of course, there have been a whole host of screen writers amongst our actresses. For instance, Naval has written her new film — the very eloquently titled Char Paise Ki Dhoop Do Anne Ki Baarish. Who can forget wonder-girl Sheetal, who handled everything from writing to set-designing to directing and acting in her turnip of a film, Honey (there is an award on its head, we hear). Trivialities aside, we know of Aparna Sen’s and Honey Irani’s contributions as writers of off-beat and mainstream cinema respectively. They were both actresses first. When it comes to Sen, she’s rather much more than that, not just because of her long list of accomplishments but because she embodies the kind of woman who is never one to suffer fools lightly. Yes, men may find that intimidating but time and again, in her cinema, she has represented women as rounded, complete individuals; and if they’re held down by constraints, they ultimately manage to find a way to shake off the shackles (Rakhee in Parama). Sen is a part of her own narratives, imbuing her world view on her women, as a director and writer, and by sometimes even inhabiting the worlds she seeks to weave into celluloid. [caption id=“attachment_52736” align=“alignleft” width=“370” caption=“Image courtesy: Film Impressions”]  [/caption] When she wasn’t pining away in her films, Meena Kumari gave us one of the few portrayals of an intelligent well-read woman on screen. She played a poetess in Gazal, struggling to hold her own in a decidedly patriarchal set-up. More poetesses abound, like Rekha in her signature role in Umrao Jaan, Tabu in Takshak, and countless women who have played Meerabai over the years (from MS Subbulakshmi to Hema Malini). This trope allows the woman a measure of intelligence with de-sexualising her. Hence, she can spout her verses and sing her rhymes, as long as she’s decked up in chakmak odhnis and lit up like a Christmas tree. Nutan in Zindagi Ya Toofan is the master of ceremonies in a wonderful majlish — a mushaira in which women are the only participants. She always seemed to bring to her parts a degree of self-effacement that almost undermines the intelligence that she otherwise radiates quite spontaneously. That was her way of staying under the radar, hereby ensuring a longevity to her acting career not usually witnessed by women, although in the 70s she did try to break out of her straitjacket in films like Kasturi, where she played a temperamental botany professor. Needless to say, the highbrow Nutan bit the dust, and the parochial one from films like Main Tulsi Teri Aangan Ki lived on for the ages. Brainy girl = Lonely life? In films like Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Chupke Chupke, the women studied botany, not to become botanists or proprietors of green-houses or whatever it is that students of botany become, but merely to complete an education which was considered an end in itself. The middle cinema of the 70s took upon itself the role of flag-bearer for a kind of progressiveness lite. Jaya Bhaduri was the poster-girl for this new ‘Educating the Girl Child’ campaign. She started off as school-girl in plaits in Guddi, then acquired some maxis with floral patterns that she wore to college in films like Phagun and Mili, always with a book or two tucked under her arms like a style statement, but later when she actually became an academic of note, in Kora Kagaz, she was doomed to a life of loneliness having been abandoned by her rather egoistic husband. In Namak Haram, Simi Garewal played a sociology major who provides her fiance (Amitabh Bachchan) intellectual succor, and she is especially insightful of the conflict that is inherent in Bachchan’s friendship with his worker-class friend. Although ostensibly planted in the factory as a mole, his friend (played by Rajesh Khanna) gradually wakes up to his own identity, and Garewal, watching from a vantage, unravels the confusion that results in both men’s lives with reserves of empathy laced with the kind of perception that held in its crux the ideological themes for the entire film. In this film, Garewal (much derided for her cloying TV appearances these days) was the true cerebral woman who never got her due in Indian cinema, and never again was a woman allowed to do this much intellectual heavy lifting in cinema (although Ayesha Mohan in Gulaal tried very hard). Elsewhere, there may have been a few articulate lawyers and some persuasive con-women (mostly played by Sridevi in ostrich feathers). Kitu Gidwani who gets all the ‘smart woman’ parts these days (in Fashion & Dhobi Ghat) is only given a scene and a half to prove her mettle. Given the 2G fallout, this can be called the era of enablers like the shape-shifting Niira Radia (and indeed a few biopics are on the way) and her voluble journalist lackeys like Barkha Dutt (who has already managed some screen incarnations), and incarcerated poetesses like Kanimozhi, therefore intelligent women as prime movers can make a re-appearance in our cinema but they’ll still speak from the gut, or from the heart, or from the belly, and not usually from the head. Till then we can make do with attractively nerdy women like the one Radhika Apte plays in Shor in the City, at least she’s allowed to outshine her husband when it comes to comprehending pirated bestsellers. The writer of this piece runs the theatre appreciation website Stage Impressions. Read the unabridged version of the essay over at Film Impressions.

To have a cerebral woman hold sway in a filmi narrative is the final frontier.

Advertisement

End of Article

Written by Film Impressions

Why FILM IMPRESSIONS? Because we believe film lovers deserve better. The quality of film criticism in India has been steadily deteriorating, losing its credibility and intellectual rigour. Instead of informed and unbiased opinion we have been subjected to publicity-driven writing, often manipulated by vested interests. We wish to offer well-argued criticism, insightful interviews, historical perspective... and celebrate cinema in all its glory see more

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)