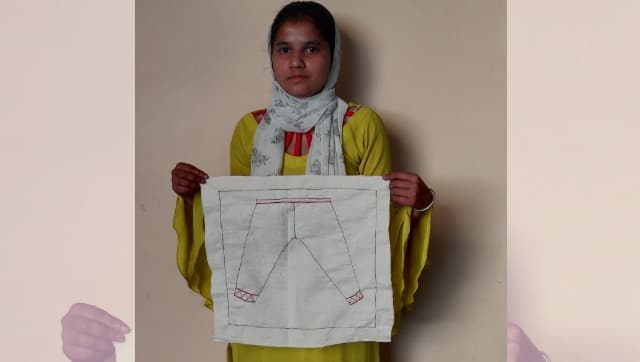

In her 20s, Jaza Parveen is introduced to me by the artist Arshi Ahmadzai as a “warrior”. Jaza is among the first women of her community in Najibabad, Uttar Pradesh, to pursue higher education. “I managed to finish my graduation with great difficulty, after which, I was told to discontinue my education,” she says. Instead, Jaza quietly applied for a Master’s in Sociology. “Every day I am told that I will be married off soon. In community gatherings, functions, I am given strange looks and taunted.” When Arshi Ahmadzai conceptualised “Lihaaf”, a quilting project, she brought together Jaza and 20 other women from Najibabad to work on a seven-metre scroll. The women are of varying ages, of Muslim faith, and belong to the Nat community. As they worked on the scroll, they sang bhajans, recited verses from the Quran, and traded life stories. [caption id=“attachment_8699211” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

Jaza Parveen, one of the collaborators on Lihaaf-The Quilt[/caption] Jaza stitched the pattern of a salwar on the scroll. Arshi recounts how she gave Jaza Manto’s Kali Shalwar to read, and why the story resonated with the young woman: “Jaza tells me she is not allowed to wear jeans by her family. She can only wear salwar kameez. A piece of cloth is used as a marker of being a righteous and obedient woman… It’s a battle Jaza has to fight on a daily basis,” Arshi says. I spoke with Arshi, Jaza and several other women from the Lihaaf-The Quilt project over a video call last month. Their work (Lihaaf is realised within the framework of

Five Million Incidents

, 2019-2020, conceived by Goethe-Institut/Max Mueller Bhavan in collaboration with Raqs Media Collective) was meant to be exhibited in April this year, but had to be postponed due to the coronavirus pandemic. Its making can presently be viewed

on Instagram

. Arshi has a Bachelor’s in Fine Arts from Aligarh Muslim University and a Master’s from Jamia Millia Islamia. Her art practice reflects on women’s issues, and is rooted in personal experiences. Born and raised in Najibabad, Arshi, who is of Afghan descent, now shuttles between Delhi and Kabul. [caption id=“attachment_8699221” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

Jaza Parveen, one of the collaborators on Lihaaf-The Quilt[/caption] Jaza stitched the pattern of a salwar on the scroll. Arshi recounts how she gave Jaza Manto’s Kali Shalwar to read, and why the story resonated with the young woman: “Jaza tells me she is not allowed to wear jeans by her family. She can only wear salwar kameez. A piece of cloth is used as a marker of being a righteous and obedient woman… It’s a battle Jaza has to fight on a daily basis,” Arshi says. I spoke with Arshi, Jaza and several other women from the Lihaaf-The Quilt project over a video call last month. Their work (Lihaaf is realised within the framework of

Five Million Incidents

, 2019-2020, conceived by Goethe-Institut/Max Mueller Bhavan in collaboration with Raqs Media Collective) was meant to be exhibited in April this year, but had to be postponed due to the coronavirus pandemic. Its making can presently be viewed

on Instagram

. Arshi has a Bachelor’s in Fine Arts from Aligarh Muslim University and a Master’s from Jamia Millia Islamia. Her art practice reflects on women’s issues, and is rooted in personal experiences. Born and raised in Najibabad, Arshi, who is of Afghan descent, now shuttles between Delhi and Kabul. [caption id=“attachment_8699221” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

(L) Women work on the seven-metre scroll; (R) a Lihaaf collaborator holds up her work[/caption] The Lihaaf project shares its name with an Ismat Chughtai short story, and draws on Arshi’s close observations of the injustices borne by women. “Girls’ education is still such a big deal in my community,” says Arshi. “My education was challenged by so many relatives but my parents supported me. My mother writes beautifully but she couldn’t go anywhere with it. She keeps a diary and I have seen how she would write [in it] every day only to place it in the junkyard of the house.” For Arshi, art doesn’t occur in isolation; it has to be in service of society, and that also explains why it was so important for her to make Lihaaf-The Quilt a collaborative experience. Initially, Arshi asked the women to embroider any pattern of their choice, but when they expressed reluctance, she drew images they could work with instead. (Najibabad is known for the vanishing craft of darning or rafugari and is the hotspot of the kani shawl trade, so the women are highly skilled in these jobs but were apprehensive to come up with their own patterns for Lihaaf because of the context.) Arshi’s imagery was all in relation to women —doors, chairs, roses, trees, figures of women. In addition to the main scroll, the women also worked on patches of different sizes. Some stitched their names on the fabric while others embroidered words like ‘Aurat’ ‘Stri’ ‘Zan’, in Hindi and Urdu.

(L) Women work on the seven-metre scroll; (R) a Lihaaf collaborator holds up her work[/caption] The Lihaaf project shares its name with an Ismat Chughtai short story, and draws on Arshi’s close observations of the injustices borne by women. “Girls’ education is still such a big deal in my community,” says Arshi. “My education was challenged by so many relatives but my parents supported me. My mother writes beautifully but she couldn’t go anywhere with it. She keeps a diary and I have seen how she would write [in it] every day only to place it in the junkyard of the house.” For Arshi, art doesn’t occur in isolation; it has to be in service of society, and that also explains why it was so important for her to make Lihaaf-The Quilt a collaborative experience. Initially, Arshi asked the women to embroider any pattern of their choice, but when they expressed reluctance, she drew images they could work with instead. (Najibabad is known for the vanishing craft of darning or rafugari and is the hotspot of the kani shawl trade, so the women are highly skilled in these jobs but were apprehensive to come up with their own patterns for Lihaaf because of the context.) Arshi’s imagery was all in relation to women —doors, chairs, roses, trees, figures of women. In addition to the main scroll, the women also worked on patches of different sizes. Some stitched their names on the fabric while others embroidered words like ‘Aurat’ ‘Stri’ ‘Zan’, in Hindi and Urdu.

— All photos and video courtesy Arshi Ahmadzai

)