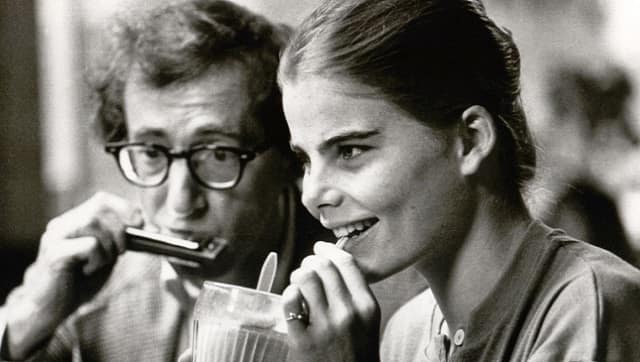

I first saw New York through Woody Allen’s eyes; way before my feet landed in the city, my eyes knew the Boating Lake in Central Park, the Queensboro Bridge, the Washington Square Park arch. In 2015, I moved to the city to study cinema, a decision that I partly attribute to my voracious watching of his films which romanticised the city so much that I couldn’t say no when there was a chance to live and work there. For most of my life, even before I studied cinema, Allen has been present in the periphery of the culture I consumed — he made films, I watched them; he said, I listened. With rapt eyes, with an open heart, in disbelief of the impossibility of his endless genius. Till, of course, Dylan Farrow’s 2017 op-ed for the Los Angeles Times, “Why has the #MeToo revolution spared Woody Allen?” educated me about a side to Allen that was first heartbreaking, then infuriating, and upon a further close-reading of his films, always sitting there, waiting to be discovered. “Separate the artist from their art,” is something we, as audiences and critics, often tell ourselves to ease the blow of dejection that comes with knowing that we have idolised a morally degenerate artist — be it Roman Polanski, Louis CK, or Woody Allen. One can cite Barthes and believe that the author is dead but with Allen, as the recent docu-series Allen v Farrow shows us, the artist and the art are inseparable: The man who would go on to face charges accusing him of sexually abusing his seven-year-old adoptive daughter, Dylan Farrow, is the one who made Manhattan. Allen V Farrow: HBO docuseries on sexual abuse allegations against Woody Allen is a portrait of a family in distress In Manhattan, Allen’s 42-year-old character, Isaac Davis, “dates” a 17-year-old school student, Tracy. I use quotation marks not just because an autonomous romantic relationship is barely possible with so much imbalance of power but also because it brushes against the fringes of legality in New York City. At 17, Tracy is just about legal to provide consent to a sexual relationship. Allen’s insistence on a virginal, pure, much younger female protagonist (often pitted against a more jaded, “eccentric” older female lead) runs as a narrative thread through several of his films. It’s almost like he whetted our appetite for his moral corruptness and then kept feeding us more of it. As an erstwhile fan of his work, my larger disbelief is that I lapped it all up and kept asking for more. [caption id=“attachment_9424921” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Still from Manhattan[/caption] For years we have used Freud’s theories of child sexuality to legitimise predation and sexual abuse, and Woody Allen has always been acutely aware of the fence his audiences sit on regarding this. His films, in retrospect, all seem to be attempts at helping them get off the fence and walk over to his side. So that when the stories of his predatory behaviour break, people have stomached his moral detours and are no longer judging him for it. We all tried to separate the man from his art till it became obvious that both his life and art were products of an extremely manipulative mind. In 2017, New York artist Jaishri Abichandani protested outside the Met Breuer in response to a retrospective of photographer Raghubir Singh’s work taking place inside. Abichandani alleges that Singh had sexually abused her in the 1990s when she was working with him. Protestors stood outside the museum silently holding up red placards that said, “Me Too”, while Abichandani’s placard read, “I Survived…Ragubhir Singh. Me Too”. The museum had extended full support to the staging of this protest. In an interview around the same time, Abichandani had spoken about the intent behind the protest. She wanted to make sure that every time someone ran a Google search on Raghubir Singh, they’d know of his fantastic art but also the fact that he was a sexual abuser, a man who took advantage of a young girl’s helplessness. I think the answer to the question, “What do we do with Woody Allen’s films?” lies in doing something similar. To bring an end to any conversation that tries to talk of his artistic legacy without examining his history of sexual abuse, without talking about the inappropriate nature of his relationship with his wife — former partner Mia Farrow’s adoptive daughter — Soon-Yi Previn, and of his denial of Dylan Farrow’s allegations by resorting to victim-blaming and name-calling. [caption id=“attachment_9424931” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Allen with Mia Farrow and family. Screengrab from HBO’s Allen V Farrow[/caption] While I personally find it hard to appreciate the technical aspects of Woody Allen’s films anymore, I don’t think the answer to anything lies in censorship — especially of the works of a man lauded as an auteur. While as a film critic, I cannot ask people to stop watching his films, I would like to prevent him from getting any richer, from perpetuating a career that is already immensely problematic. As an audience, we have been gaslit by Woody Allen’s films and what prevents us from having constructive conversations about the ways in which we can talk about his artistic legacy, is that half of us are busy planning his unexamined resurrection and the other half is suffering through self-induced guilt, forever asking ourselves, “Had we always known?” The point is, it doesn’t matter because now we know, and what matters is what we do with this knowledge. Woody Allen’s works have to co-exist with their takedown. To call it “cancel culture” and bemoan the loss of the white artist’s freedom to create any irresponsible art that they please, is to aid a culture that continues to ridicule a survivor’s account of abuse, and strengthens the abuser’s right to push their lopsided story forward. Film history, the way we’ve had it taught, is an unexamined canon of largely white men that is crying to be reassessed. There has to be a prevailing culture of consequences where an abusive man can’t keep escaping charges that are brought against him, where he can’t keep making irresponsible art. Woody Allen, the man, the artist, the author, the abuser, is far from being dead. He lives on the Upper East Side and still gets enough money to make a new film.

We must bring an end to any conversation that tries to talk of Woody Allen’s artistic legacy without examining his history of alleged sexual abuse.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)