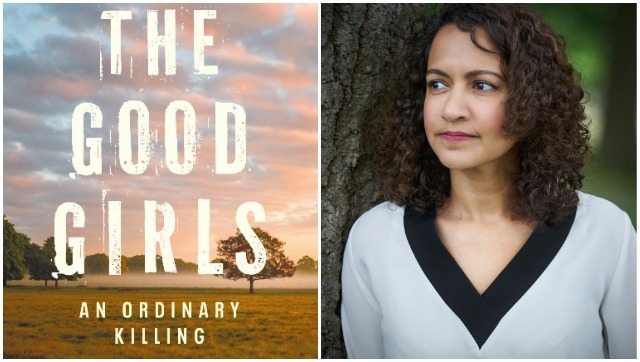

“If the Delhi bus rape was met with horror, the hangings in Budaun were reflected on with despair,” writes Sonia Faleiro in The Good Girls. Like most urban Indians, Faleiro first came across the 2014 news of the deaths of two teenage girls in an Uttar Pradesh village on social media — Twitter, more specifically. The disturbing image of the girls hanging from a tree was being circulated along with reports that they had been raped and murdered by caste-dominant men. There was a feeling of despair and outrage over the plight of women in rural India, and the state of law and order in India’s most populous state. With the Delhi rape case and the ensuing media coverage of similar incidents, Faleiro had decided to dig deeper by gathering her findings in a book-length study of rape in India. But the fact that the Katra case became the highest profile sexual assault case (after the Delhi rape) drove her to make it the centrepiece of the study. In the spring of 2015, one year after the girls were found dead, the London-based author set off for Katra. Her meticulously researched book, The Good Girls, is a result of the four years she spent reporting in the region, conducting hundreds of interviews and combing through piles of CBI records and written investigations. It’s perhaps fitting then that Faleiro opens the book opens with an index of characters, from the girls’ family members (the Shakyas) to others residing in Katra, members of the accused’s family, politicians, the police, the CBI, and the post-mortem team. For her, the story was never just about the two cousins, 16-year-old Padma and 14-year-old Lalli (names changed). “Individuals don’t exist in isolation. We are all part of something bigger and this was particularly true of Padma and Lalli. First of all because they were children, and had very limited agency. So their family and close relationships really influenced a large part of their lives — it influenced what they had to do, how they had to spend their entire day, their access to education, technology, to modern ideas and to modern ways,” she says, in a phone interview from her home in London. Like her previous book Beautiful Thing (2010), The Good Girls features Faleiro’s signature narrative-style reportage and unfolds like a gripping mystery. She recreates scenes days, weeks and months after the incident, supplementing it with a range of perspectives from important characters. She says that it was important for her to understand the world of the people she was reporting about, and to present that world in as accurate, intimate and vivid detail as possible. “Non-fiction is not just about acquiring information. It’s also understanding what that information means, understanding the context of people’s lives. People are much more than the words that come out of their mouth — they are their lived experience, their circumstance, their history,” she adds. One of the more fascinating characters in the story is Nazru, a 26-year-old who is a cousin of the girls’ fathers. He was a prime witness in the case, having been the last one to see the girls before they disappeared that night. Nazru changed his narration of what he had witnessed several times, from claiming to see thieves to saying Pappu Yadav (the prime accused from a neighbouring hamlet) had taken the girls, to then modifying the story saying it was Pappu and three other men, one of whom had a gun. Faleiro says interviewing people who constantly change their stories is a challenge reporters face in the course of their work. “It’s not unusual for people to present falsehoods. Because we live in urban India, we think of ourselves as individuals with rights and privileges, and forget that most people in the country understand that their words and actions don’t simply affect them. There’s the notion of honour — you don’t just speak for yourself, but for your family, your community, your caste and so on.” When the photo of the girls surfaced on social media, the pressure of instant news led many journalists to misreport facts in the case. One of the biggest inaccuracies was the caste angle — that the girls were Dalit whereas the perpetrator Pappu belonged to a higher caste. This sharpened their experience of victimisation when the truth was that both families belonged to the lower-caste OBC category — the Yadavs were just considered politically powerful, with a political party having gained clout in the state over the years. According to Faleiro, this misrepresentation only reinforced the disdain people in Katra held for the media. “The Shakya family did not have TVs, didn’t listen to the radio and didn’t read the papers. And yet they had a distrust of the media. They are not convinced that the media is capable or is interested in reporting the facts.” The extraordinary thing for the author was the fact that the Shakyas knew exactly what had happened in the Nirbhaya case and had cottoned on to the value and power of protest. This explained why the family refused to get the girls’ bodies down from the tree for several hours — they didn’t trust the police and believed that if the bodies were brought down, the matter would end in the village. They wanted the most powerful people in the country to see them. The Shakya family believed that “the wheels of justice move only under pressure from the powerful”, she writes. “Their protest was a direct response to the successful protest in the Nirbhaya case. Information had not just travelled, but also made an impression.” In the end, despite the family attracting attention from the powerful, Faleiro mentions that they were let down by every single group — the police, the politicians, and the investigators. Sohan Lal (Lalli’s father and the Shakya family patriarch) didn’t think anything good had come out of the deaths. Faleiro writes in the author’s note that while this is a story about women in modern India, it’s also about what it means to be poor — and for them, India hasn’t changed all that much. “We live in a very unequal country. We should judge systems like the police in how they respond to people with the least, not the people with the most. The Shakya family was convinced that they would be brushed off because of their caste,” she says. Nearly seven years after the incident, crimes against women continue unabated, with Uttar Pradesh topping the list. Just weeks after The Good Girls was published, two minor Dalit girls were found dead in Unnao, and days later, another minor girl in Aligarh. “Every part of the system in Uttar Pradesh is broken — the police are not doing their job, the government has vested interests, and girls are being kept out of school. But even if you keep Uttar Padesh aside, crimes are likely to occur and reoccur because the perpetrators know they will not be caught. And when I say I blame the police, I’m not pointing to some constable trudging the fields of Katra. It’s important to see who’s behind that constable. The police are not acting in a vacuum. There are people who are not paying them, not training them, telling them that there are no consequences. Ultimately the blame falls on the government because they have the money and the power. What they don’t have is the will,” she says. “One of the first things a parent teaches a child is there are consequences for bad behaviour. In India, people learn that there are no consequences. If you have imbibed this lesson, you will continue to commit the crime that you get pleasure, money or power out of.”

The culmination of four years of exhaustive research on the Budaun teenagers’ deaths, Faleiro’s new book, The Good Girls, paints a distressing picture of gendered inequalities in modern India.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)