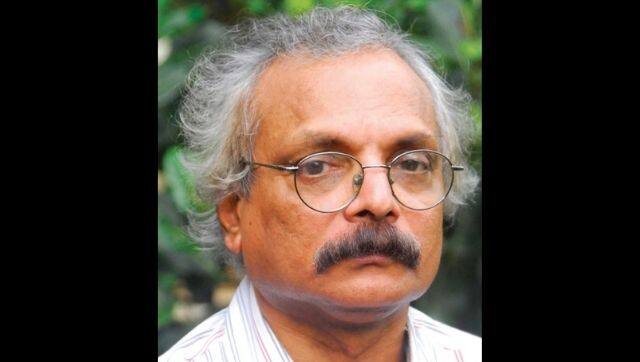

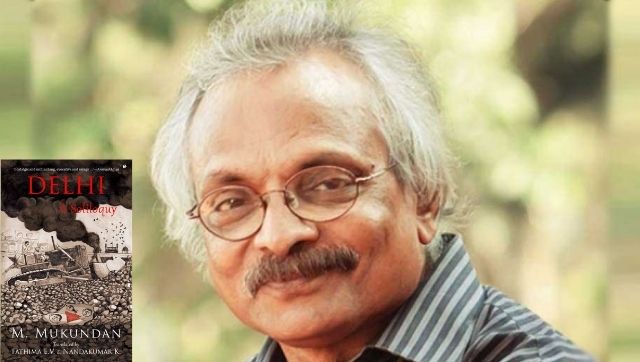

Delhi had a pivotal role to play in making a writer out of M Mukundan, the novelist confesses, having spent 40 years stationed in the capital city as the Cultural Attaché at the French embassy. The Malayalam novel Delhi: Gathakal germinated long ago in his mind, as a reflection on all the different events he had witnessed within the multicultural fabric of the capital. And at long last, he put pen to paper in 2009 to produce a novel in Malayalam about this north Indian city. It took two years for the writer to paint a picture of Delhi which was far from the glamorous and ‘cosmetic’ construct of the city in those minds that have never truly visited the capital. Mukundan says, “Delhi’s underbelly is laden with squalor and misery. I wanted to talk about these dark sides of the city.” [caption id=“attachment_8831461” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  The Sahitya Akademi Award-winning author talks not about the glamorous aspects of Delhi but about the squalor and destitution which goes unobserved by tourists visiting the city.[/caption] Recently translated into English by Fathima EV and Nandakumar K, Delhi: A Soliloquy is the story of Sahadevan, a dreamer who wishes to one day record his experiences in a novel – of living and working in the city and his interactions with the colourful people he meets there. In the translators’ depiction of Delhi, it is evident that Mukundan’s sharp gaze captured the events the city suffered from after independence, transforming it into a vibrant character whose heart beats to its own rhythms. Delhi was a very small place when Mukundan set foot there in the early 1960s. “Where now Kailash Colony stands, there were cauliflower and wheat fields,” he says, recalling that he would take long walks in these open spaces. Delhi was also a very safe city back in the day, the Sahitya Akademi Award-winning writer notes, such that his neighbours in Lajpat Nagar – men, women and children – would all be found sleeping outside their homes, lying on charpoys by the roadside without locking their front doors.

“One day, I saw Prime Minister Nehru getting down from a car in Queensway (now Janpath) with a young Indira Gandhi, without any police escort.”

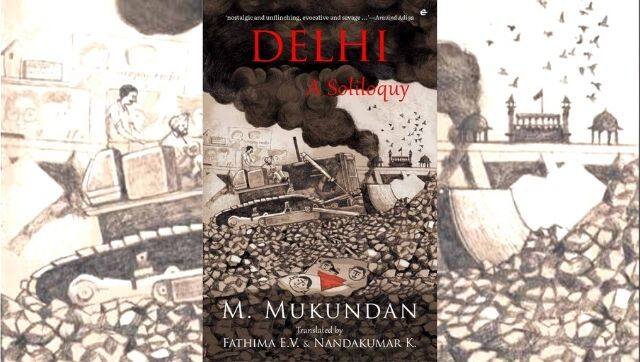

However, elaborating on the changing façade of the metropolis, the author rues that today Delhi has become one of the most violent places in the world. He calls to attention the Nirbhaya rape case to describe the extent to which the city “is getting dehumanised and embracing sheer violence.” The incidents that Mukundan recounts in his 2011 novel are then perhaps prescient in their description of the city’s slow descent into degradation, whilst also throwing the spotlight on the Malayali community that was taking roots in the capital. “They were mostly from lower or middle class echelons and life was nothing but a struggle for them. Over the years, more and more Malayalis made Delhi their home. Some could make it to the top, becoming rich and powerful. They were very few.” And Mukundan’s book is indeed an acute description of their penury. His protagonist Sahadevan, hailing from a village in Kerala, is one among these hundreds of Malayalis who leave for Delhi in search of a job. He is too poor to buy and wear trousers — a custom for young men going to big cities for work — and instead, travels to the capital enduring the grime and sweat of the arduous train journey draped in his dhoti. From finding a bed to sleep on, to securing two full meals a day, everything poses a challenge. But as is the case today, the community sentiment was strong back then as well, and Sahadevan manages to find a home in the family of the trade union leader, Shreedharaunni. He becomes a part of this family, a guardian and friend for the children Vidya and Sathyanathan, and together they battle the clouds of war first with Pakistan, then with China, followed by the Emergency, the 1984 Sikh riots, caste hatred and communal mistrust and the assassination of Indira Gandhi – all of which find their way into Sahadevan’s narrative. Mukundan, who bore witness to much of this social and political turmoil unfolding in the city, says that it was the poor who were hit the hardest, as is the norm. “The excesses committed during the Emergency were heart breaking,” the novelist says. The poor “were forcefully taken for vasectomy. Shops were demolished. Journalists and intellectuals were thrown into prison. I’ve described all these in the novel.” To be in the capital city amidst many a national crisis would have meant bearing witness to the brutality, violence and politics perpetrated within its historic premises. Mukundan describes in particular the day when Indira Gandhi was shot and how he walked over from his office in Hauz Khas to the AIIMS hospital where she was admitted. The scene outside the hospital was chaotic, he recalls. “Women were wailing, beating their chests; police vehicles were racing up and down. In the evening on my way back home, I witnessed a macabre scene I could never forget: near South Extension market, hooligans stopped a taxi car, pulled out the aged Sikh driver, and beat him to death.” All these incidents, including Mukundan’s descriptions of the caste and religious conflicts in the city, find their way into Fathima and Nandakumar’s iteration, a manifestation of a four-year-long translation process. Nandakumar explains that he worked on the first draft and had it checked by Mukundan, “since there were some corrections required, given that practically no fact-checking and in-depth editing happens in Malayalam”m and then it was Fathima’s turn “to check the idiom since she hails from Malabar and is more familiar with the patois used largely in the book, and the mores of the region, and do the spit and polish.” [caption id=“attachment_8831481” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Translated by Fathima EV and Nandakumar M, Delhi: A Soliloquy brings into English Mukundan’s experiences of living and working in Delhi for four decades.[/caption] For her part, Fathima says: “The language also needed to be pared down, causing some heartburn for Nandan [Nandakumar] who has a soft spot for weighty words, which I felt were out of place. However, the simple, straightforward style in which Mukundettan [Mukundan] writes did not leave much room for arguments, and we were in perfect sync most of the time.” The finished version is not only a Malayalam story translated into English, but also incorporates words and phrases from Hindi and French which have been retained to preserve the feel of a north Indian city and the offices of the French embassy. There were a lot of footnotes in the original draft, Nandakumar says. “Then our brilliant editor, Karthika, put her foot down. Her credo? Let the readers educate themselves if they want to know! Pages of footnotes shrunk to two or three in the whole book,” he recalls. On being asked how the translators retain the essence of the colloquial Malayali idiom in the English version, Fathima notes, “Localised usages, dialectical variations, and the cultural geography of Malabar seldom posed a challenge for me, because Mukundettan and I hail from the same place.” Furthermore, while Fathima sees translation as a creative interpretation, Nandakumar, she says, “believes that the translator does not aim to trans-create, but only renders the author’s words faithfully in another language.” In spite of this difference, both translators cherish the author’s endorsement of carrying the book and his voice to a new set of readers.

“All the three of us have lived away from Kerala and could easily identify with the nostalgic reminiscences of the Malayali diaspora in Delhi, and hence we believe we have been able to recreate its feel in the translation as well.”

Commenting on the role of translators in bringing forth stories that highlight the voices of regional communities, Nandakumar draws attention to the “majoritarianism, the mindless hero worship of a papier-mâché God, ghettoisation of minds” prevalent today, and states: “If the open, cosmopolitan and freewheeling Malayali ethos can be brought before the more parochial and bigoted brethren of India, if that could even in a little way, change the current narrative and mindset of the people, I would always strive for it.” Mukundan’s Delhi: A Soliloquy is a masterful rendering of the many events that shook Delhi, and the observations of one man of the sufferings it brought upon thousands of the city’s residents. As Fathima remarks, “This is a paean to Delhi, a city of heartlessness as well as astonishing kindness and solidarity, a city that strains to forget the violence that has sporadically punctuated the rhythms of life in its sequestered precincts…” Through it all, the protagonist Sahadevan is a constant, “observing, dreaming, ageing, engaging” with people, and being a Malayali narrator, he is habituated to being a political animal who cannot help but be “both a participant and an outsider, perpetually caught in a maelstrom of changes.” M Mukundan’s Delhi: A Soliloquy, translated into English by Fathima EV and Nandakumar K has been published by Eka, an imprint of Westland publications.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)