Subramania Bharati was a polyglot who wrote brilliantly in a number of languages, including English. In fact, as a poet at heart, he loved and respected the English language, which he saw, not primarily as the language of India’s oppressors, but as the language of England’s literary geniuses – Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley foremost among them, and, from Bharati’s perspective, a kindred spirit. These were writers to be admired and emulated. But his attitude of reverence for poetry and respect for language was sorely tested by British policy of the time towards what the British government dared to call India’s “vernacular” languages – the diverse and distinguished literary languages of India’s people all over the subcontinent.

Chellamma with her daughters and grandchildren; S. Vijaya Bharati is seated at front right[/caption] [caption id=“attachment_9993861” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

Chellamma with her daughters and grandchildren; S. Vijaya Bharati is seated at front right[/caption] [caption id=“attachment_9993861” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

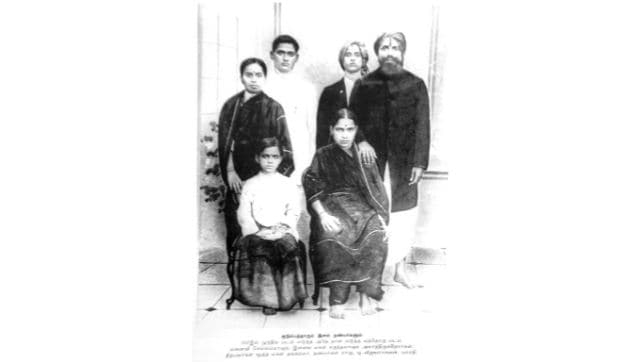

Bharati family with Chellamma, Thangammal, Shakuntala, and two of Bharati’s disciples[/caption] To argue against this trend, Bharati relied upon his extensive knowledge of Tamil literature. He described the achievements of Tamil, and called for the study of these literary accomplishments alongside those of European writers. His goal was never chauvinistic – he simply wanted Tamil to take its place among the great literary traditions of the world without threatening the achievements of other cultures. Indeed, based on his reading, he believed that Tamil should be rightfully recognized as a “mother” tradition for humanity as a whole, because of its antiquity, continuity, and literary stature. The need for a strong stance was obvious. From today’s perspective, it might seem that Bharati’s position is outmoded. English is globally dominant – the battle seems to have been lost. Indeed, by an appropriate irony, Indians’ affinity for the English language is often cited as one of the reasons why India has become a world economic and cultural power today. But Bharati was a visionary who saw far ahead of his time. In fact, his arguments in favour of preserving and promoting Tamil – and with it, India’s and the world’s linguistic diversity – are more relevant than ever before. Yet they have never actually been explored. Instead, they have been sidelined as a result of the ubiquitous presence of “business English.” Reading Bharati’s words, written in such eloquent English, should give us significant pause. As Bharati’s literary legacy enters its hundred and first year, his writings offer us a new opportunity to reflect on our own identity, and to ask the all-important question of whether we have truly achieved equality in this postcolonial world. In the meantime, the world’s languages and cultures are rapidly dying out, and climate change threatens humanity at large. These changes would appear to be the direct result of living in a world defined by colonial values that have never been fully overcome. The world seems to have lost sight of cultural diversity just when we need it most – when new ways of thinking are needed to surmount the significant challenges that lie ahead. Valuable ideas are embedded in our languages: Bharati tells us so. Taking an interest in our “mother tongues,” and making the effort to learn languages and to read, could be an important part of these efforts. Bharati helps us along, giving us a tantalizing glimpse of what it means to be a Tamilian today. In doing so, he points the way towards rediscovering the hidden treasures that lie buried within ourselves and in our collective past. It’s a potent lesson for Tamilians, Indians, and the world. — All images courtesy the author Mira T. Sundara Rajan is the editor of The Coming Age, a collection of Bharati’s original writings in the English language, published by Penguin Modern Classics, and the creator of an accompanying podcast, “

Bharati 100

”.

Bharati family with Chellamma, Thangammal, Shakuntala, and two of Bharati’s disciples[/caption] To argue against this trend, Bharati relied upon his extensive knowledge of Tamil literature. He described the achievements of Tamil, and called for the study of these literary accomplishments alongside those of European writers. His goal was never chauvinistic – he simply wanted Tamil to take its place among the great literary traditions of the world without threatening the achievements of other cultures. Indeed, based on his reading, he believed that Tamil should be rightfully recognized as a “mother” tradition for humanity as a whole, because of its antiquity, continuity, and literary stature. The need for a strong stance was obvious. From today’s perspective, it might seem that Bharati’s position is outmoded. English is globally dominant – the battle seems to have been lost. Indeed, by an appropriate irony, Indians’ affinity for the English language is often cited as one of the reasons why India has become a world economic and cultural power today. But Bharati was a visionary who saw far ahead of his time. In fact, his arguments in favour of preserving and promoting Tamil – and with it, India’s and the world’s linguistic diversity – are more relevant than ever before. Yet they have never actually been explored. Instead, they have been sidelined as a result of the ubiquitous presence of “business English.” Reading Bharati’s words, written in such eloquent English, should give us significant pause. As Bharati’s literary legacy enters its hundred and first year, his writings offer us a new opportunity to reflect on our own identity, and to ask the all-important question of whether we have truly achieved equality in this postcolonial world. In the meantime, the world’s languages and cultures are rapidly dying out, and climate change threatens humanity at large. These changes would appear to be the direct result of living in a world defined by colonial values that have never been fully overcome. The world seems to have lost sight of cultural diversity just when we need it most – when new ways of thinking are needed to surmount the significant challenges that lie ahead. Valuable ideas are embedded in our languages: Bharati tells us so. Taking an interest in our “mother tongues,” and making the effort to learn languages and to read, could be an important part of these efforts. Bharati helps us along, giving us a tantalizing glimpse of what it means to be a Tamilian today. In doing so, he points the way towards rediscovering the hidden treasures that lie buried within ourselves and in our collective past. It’s a potent lesson for Tamilians, Indians, and the world. — All images courtesy the author Mira T. Sundara Rajan is the editor of The Coming Age, a collection of Bharati’s original writings in the English language, published by Penguin Modern Classics, and the creator of an accompanying podcast, “

Bharati 100

”.

Thinker and poet C Subramania Bharati's response to British-imposed linguistic elitism

Mira T Sundara Rajan

• September 25, 2021, 08:48:17 IST

With his usual clear-sightedness, Bharati argues that promoting English education at the expense of India’s national languages would sound the death knell of their future.

Advertisement

)

Vernaculars, indeed! Bharati hated this term. It reduced his mother tongue, Tamil, the language of the last surviving classical civilization in the world, to a mere popular language spoken by a downtrodden people. According to the British, it was clearly outmoded. Neither Tamil nor any other of India’s “vernacular” languages could possibly be suited, they claimed, to a modern society based on science and reason! If Indians really wanted to improve themselves, they should be educated in English. To address these outrageous, discriminatory claims, Bharati, metaphorically speaking, draws himself up to his full stature as poet and polyglot, Tamilian and Indian and humanist. “I do not blame the Madras ‘Council of Indian Education’ for their anxiety to have Professor Geddes’ views on the subject of employing Indian languages as the media of instruction in Indian schools,” he writes, referring to the famous Scottish thinker as “good and learned.” “For I am aware that men’s thoughts are ordinarily moulded by their environments.” Bharati is able to rely upon his extraordinary breadth of reading in Indian languages, including Sanskrit and Hindi, to comment: “But I feel it is high time to remind all parties concerned in discussions like this, that most of the Indian languages have great, historic, and living literatures. Of course, their lustre has been slightly dimmed by economic conditions during these latter days.”

Sadly, the presence of the English, and the demeaning effect of colonial oppression on the Indian psyche, had already had a powerful impact. Bharati is deeply concerned about this and demands what was then unthinkable. Indians and their languages should be respected and treated as equals, at least, by the English – and, crucially, by the Indian elite. He writes: “The English-educated minority in this country can be pardoned for being frightfully ignorant of the higher phases of our national literatures; but they will do well to drop that annoying attitude of patronage and condescension when writing and talking about our languages. The Tamil language, for instance, has a living philosophical and poetic literature that is far grander, to my mind, than that of the ‘vernacular’ of England.” And here, Bharati’s polyglot reading as well as his writing allow him to make a comparison that has not yet been explored fully in the study of comparative literature: “For that matter, I do not think that any modern vernacular of Europe can boast works like the Kural of Valluvar, the Ramayana of Kamban, and the Silappadhikaram (‘Epic of the Anklet’) of Ilango. And it may not be irrelevant to add that I have read and appreciated the exquisite beauties of Shelley and of Victor Hugo in the original English and French ‘vernaculars’, and of Goethe in English translations.” In our postcolonial reality, it is of paramount importance to understand how and why Bharati stood up for the Tamil language at a time when Indian languages were in a process of active decline because of the British colonial administration in India. With his usual clear-sightedness, Bharati saw that promoting English education at the expense of India’s national languages would sound the death knell for their future. The younger generation would grow up without facility in their mother tongues. They would be dispossessed of their native languages, their rightful heritage, while English took the place of those languages in their minds and lives. The longer- term consequences would be stark – the disappearance, not only of national languages as media of education, but also of the lifestyles, traditions, culture, and knowledge embedded in those languages. [caption id=“attachment_9993851” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]

End of Article