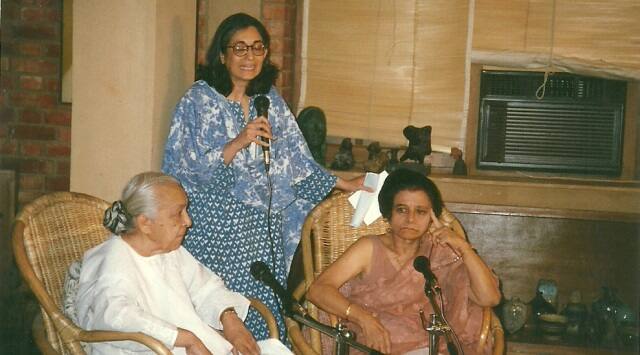

Listening to Ritu Menon is an education in itself. She holds within her a living archive of stories about feminist publishing, the women’s movement in South Asia, and the commitments of people across borders who have taken great risks and nurtured long-term relationships of care and solidarity. Over a Zoom call, we talk about Address Book: A Publishing Memoir in the time of COVID, which she wrote during the pandemic without an explicit plan to create a book. “It became a form of putting down what I was going through, remembering, thinking, reading, and worrying about,” she says. The book will take you on a literary pilgrimage as Menon cobbles together recollections of the stalwarts she has worked with – Ismat Chughtai, Qurratulain Hyder, Zohra Segal, Nabaneeta Dev Sen, Nawal El Saadawi, Haifa Zangana, Devaki Jain, and Taslima Nasreen, among many others. It has been published by Women Unlimited, an associate of Kali for Women that was co-founded by Menon along with Urvashi Butalia. While Menon heads Women Unlimited, Butalia heads Zubaan. Edited excerpts from an interview: When the story of independent publishing is told, the focus is often on the challenges and hardships. Tell us about the joys. What are you able to do that big publishing houses cannot? I am able to do exactly what I want without having to justify it or pitch it or sell it or convince people that I am going to produce a blockbusting book. I have the freedom to publish the kind of books that I want to without having a legal department breathe down my neck or a finance department saying that we have too much to lose. I can develop a list the way I want to. If I had been part of a larger publishing house, I would never have been able to initiate the series I called Arabesque. It is not economically viable, but it is a literary, political and personal commitment. I am able to introduce readers in India to some of the most fantastic writing that is available currently from a region in the world that we know very little about and strangely enough have very little curiosity about even though historically India has had strong links with West Asia. We are going to publish a book of testimonies by Palestinian women prisoners in Israel prisons. It is an act of bearing witness to the struggles of people who have been under occupation for over 50 years. We in India are quite Anglophone in our interests, and the book trade in India is dominated by English language publishing. It has become even stronger with the entry of multinational corporations. As an independent publisher producing books in English, we are part of that ecosystem. We must find a place for ourselves in that environment – either become part of a large corporate set up or be independent with a strong profile. We have chosen the latter. This means that decisions about what we select, publish and make available must have integrity of content. There was nothing to stop us from publishing all kinds of fiction, but we decided to focus on fiction in translation. Why? Because no one was doing it when we started. Now it has become a big thing. We started it more than 35 years ago because we wanted to publish women writers in translation. It was not economically viable then, and it is not viable now. We did it, and we will continue to do it. It is labour-intensive, has a long gestation period, and the returns are low. Translation in a multilingual country like India presents many challenges, not the least of which is getting good translations. It is a labour of love. Large corporations are not into love; they are into business. They may pretend to do some radical and out of the ordinary things. That is not their main agenda. What gave you the courage to start your own publishing house – Kali for Women – with Urvashi Butalia after having worked with Doubleday in New York and other publishers in Delhi? It was a conjunction of circumstances. One was the women’s movement, of course! Then there was the fact that no one in India had thought it possible and feasible to set up a publishing house with one single focus – publishing a whole range of books from a feminist perspective. We also realised that it was an area with a large potential. We started Kali for Women in 1984. Friends of ours in publishing said, “There is no market for this.” We told them, “The market needs to be developed.” Then they asked us, “Where are the writers?” We said, “The writers too need to be developed.” This time, they asked, “Where are the readers?” And we said, “There are readers, but we don’t know yet where they are.” Feminist publishing worldwide is a development activity. It is not just about producing books. It is part of a huge enterprise. Apart from the women’s movement and the women’s studies movement, which happened across the world at the same time, we had the women in print movement. It was made up of a few publishers but also had women librarians, reviewers, designers, printers, binders, bookstore owners, and of course, writers and readers. It was a supportive community where we reinforced each other. It was not present so much within India, but it was active across the world, from North America to Australia. Gradually, it developed within South Asia as well. We were very much part of that South Asia experience because the women’s movement in South Asia was very regional, eclectic, open and progressive. All our countries might have been at odds and in conflict with each other. There was trouble on the borders but, for the women’s movement, there was a transcending of those borders. We could forge these links because we were independent, small and autonomous. We were part of workshops and activism. We were out on the streets, participating in demonstrations, and being petitioners in the Supreme Court along with other women’s groups fighting against sexual harassment at the workplace. That’s what led to the Vishaka guidelines. No other publishing house, corporate or otherwise, would have allowed that. We needed to have a defined profile to set us apart. When people came to us, they knew what our strengths were. My friend Chandralekha, the dancer, who made the logo for us, had a slogan – Woman, born of the fire of consciousness! This fire is absolutely invaluable. Once you have it, it’s not possible to not have it. [caption id=“attachment_9797001” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Cover of Ritu Menon’s new book Address Book: A Publishing Memoir in the time of COVID[/caption] How did you get to know Urvashi? How did you come together? We got to know each other when she was with Oxford University Press. I was with Vikas, and before that, with Orient Longman. Then she went to London. I was in Delhi. I heard from a mutual friend that she was coming back to India. We were both interested in publishing from a gender perspective. She was with Zed Books. I was working on an imprint called Shakti that Vikas had started. When I heard that she was coming back, I thought: Why not start something together? People thought it was a shot in the dark. We didn’t know whether it would work. We had no money. But we both came from the world of publishing. We were professionals, so it was not like we didn’t know what we were doing. We had links with the book trade and with prospective authors. All of our earliest books were commissioned. The writing and the writers had to be thoughtfully developed. One of our most successful writers, Vandana Shiva, had not written a book until she began writing for us. She used to say, “I’m not a writer. I’m an activist.” She has never stopped writing since she wrote for us. We used to pursue ideas that needed to be written about. That was a very exciting time. To be at the beginning of something and trying to make it happen was really exhilarating. I remember being with Urvashi at the first International Feminist Book Fair in London in 1984. We were listening to Ellen Kuzwayo. Her book had just been published by The Women’s Press. She spoke a phrase which became the title of one of the first books we published. She said that, in South Africa, “the history of doing” is more important than the history of writing. Both of us looked at each other and said it would make the perfect title for Radha Kumar’s book, which we were publishing – The History of Doing: An Illustrated Account of Movements for Women’s Rights and Feminism in India. We had so many serendipitous and sublime publishing moments. I have tried to capture all of them in my memoir Address Book. It was energising for me to relive that period of not just hope and optimism, but also the possibility of being able to effect change through what we were doing. Working on this book gave me a chance to recall all those accidental encounters, people, books, friendships, issues, how we came up on certain things, and how certain ideas took hold. I thought that it was a very original way of writing a memoir by going through the names and addresses of people that I have worked with across the world. I had never intended to do this, but it became a geographical mapping. It affirmed the internationalism of what we were doing. Would you say that your priorities as a publisher changed when there was a shift from Kali for Women to Women Unlimited and Zubaan, one run by you and the other by Urvashi? Not at all. Neither for me, nor for Urvashi. I can say that confidently. Our priorities have not changed, but the context in which we are working has changed. The 21st century has been a sharply distinct century for all communication media. The rise of the digital environment has made a significant difference to what we do. It has changed the definition of a book. There was no such thing as an e-book or flash fiction or the concept of reading on your mobile phone. There has also been a big shift in the political environment, mainly a decline of left leaning and progressive politics, of which we are very much a part. There has been a steady shift towards the right, and a kind of conservatism despite a superficial modernity. And then, of course, we have had the entry of the multinationals from the mid-90s. In the first 10 years, we had a much more level playing field. We were tiny. We had no money, but the environment was relatively equal. Look at what has happened to independent publishers all over the world. Zed has been absorbed by Bloomsbury. The Women’s Press has stopped. Pandora has wound up. Virago is now part of Cape. [caption id=“attachment_9797011” align=“alignnone” width=“640”]  Zohra Segal, Ritu Menon, Amita Malik (left to right) at the launch of Zohra Segal’s book in 1997.[/caption] Apart from the definition of the book, would you say that the definition of feminism has also changed? Now we have more queer and trans voices calling out people whom we saw as major figures in the feminist movement earlier. As a feminist publisher, do you have to keep your ear to the ground in terms of what’s happening in the movement itself? Feminism has never had a singular definition. It has always been fluid, open and evolving. There is no authoritative voice, high priestess or presiding deity. There is no foundational work that everyone has to prescribe to. It has no sworn allegiances. And it has changed from place to place. There used to be a slogan called ‘sisterhood is global’. That was junked decades ago by feminists from the south who said that there is solidarity but no such thing as global sisterhood. Feminism has always been expansive. There has been a continuing resistance from within. If there are a lot of voices challenging so called established or recognised or hitherto accepted voices, that is a very healthy development. One of the problems with Marxism is that it has remained closed. If Karl Marx were alive today, he would be a feminist. He would have understood the importance of patriarchal control that predates labour and capital. He would have understood the critical importance of sexuality and sexual politics. Marxism is nowhere more closed than in India. If feminism were to go the same route, it would be a dead duck. A call for accountability in feminist circles has been circulated recently in response to video clips featuring Kamla Bhasin, one of the authors that you have worked closely with. When instances like this happen, how do you respond? I think it is very important that issues are raised, but it should not become an occasion for settling scores. The questions and issues that have been raised are important and valid. Not just with regard to Kamla but several iconic figureheads within the feminist constellation in South Asia. These questions have been raised in Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Bangladesh, and for quite some time now. They are not new. What is different is that the voices are much louder, and there are many voices. The unfortunate thing about the current moment is that such conversations can only be done online. This, I think, is not a satisfactory form of discussion for issues that are so critical and so intimate. There must be a safe environment for it to happen. I remember that when discussions on lesbianism began in India in the late 1980s, there were groups in Delhi that were open only to lesbians because they needed a safe space. Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code was still around. Safe and open spaces are required when we want to talk about things like accountability. I know that it has been a very charged discussion, like the MeToo discussion that happened earlier with Raya Sarkar’s list (List of Sexual Harassers in Academia, also called LoSHA). Unfortunately, discussions are beginning to freeze into certain positions, which I do not see as being a very productive engagement. How important has it been for you to see yourself as a South Asian? Very important! It is a direct consequence of my being part of the women’s movement. We have published many writers from Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Bangladesh. We have shared history and culture, and so many languages in common. I am not a great believer in territorial boundaries. For the women’s movement in South Asia, it has been important to establish solidarities across national borders, to express and affirm and provide that solidarity to each other. That is why it was important for us to publish Taslima Nasreen. She stood for something. She raised her voice at great personal risk, and she continues to live with the consequences of the choices she made. As we talk about extremisms and fundamentalisms and the hardening of boundaries, I recall that moment from Address Book where you write about listening to Iqbal Bano singing Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s poem Hum Dekhenge at Al Hamra in Lahore. What was it like to be there? It was phenomenal! The kind of duress that people were living under in Zia-ul-Haq’s time is difficult to imagine. There was a constant anxiety about what you said and who you met. To hear a woman like Iqbal Bano in the open, in public, making this declaration and saying ‘We will see who survives and who endures’… You cannot imagine the roar of people. Everybody stood up. It was electrifying. What can’t we learn from the women’s movement in Pakistan in the 1980s, the only force that was resisting Zia-ul-Haq at every turn? Imagine the courage of that! Now it is becoming difficult to visit, almost impossible. But those links have to be kept alive. We need them. * Chintan Girish Modi is a writer, educator and researcher who tweets @chintan_connect

Address Book takes the reader on a literary pilgrimage as Menon cobbles together recollections of the stalwarts she has worked with.

Advertisement

End of Article

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)